This is a translation of the post

Urtext = Klartext? – eine Analyse der Sarabande in Es-Dur, Teil 3 (Takt 25-32)

by Dr. Marshall Tuttle.

Michael Bach

This is the third part of the analysis of the

Sarabande in E Flat Major

with performance examples

and the interpretations of the cello competition *)

For glossary, slur-code and facsimile of the manuscript of Anna Magdalena Bach see Analysis Part I:

https://www.bach-bogen.de/blog/thebachupdate/urtext-plain-text-an-analysis-of-the-sarabande-in-eb-major-part-1

Sarabande in Eb Major, Edition Michael Bach

Sheet music sample mm 25-28

Slurs that are understood from the polyphony and that JSB therefore did not have to notate are added in parentheses.

M 25f

Measures 25 and 26 correspond, in this case a fifth lower, melodically and harmonically to mm 9 and 10. Again, there are two possible harmonic progressions that are parallel, in major or in minor (tonic-Sub or DR-Rel).

M 27

Measure 27 is similar to M 11, launched with a tied note. Now the DR (respectively Dom) is expected here analogous to the previous example. The short irritating sixteenth note Ab3: Does this mean a transformation to the D7-chord? The answer lies in the quarter note in the bass, so that the upper voice is slurred and the note Ab3 can not be clearly classified as a chord tone of the D7-chord, but rather as a passing or suspended tone (see, in contrast, the mm 6, 16 and 18 where the sixteenth can be construed as chord tones).

Important in this context is that this note is tied, and thereafter the emphasis will be placed on the root of the DR, G3. However, the irritation of the coincidence of both pitches of the minor seventh (Bb2-Ab3) may well be highlighted since this peculiarity, a dissonance on the fourth sixteenth note of the first beat, already found in the previous measure continues in the following measures.

Also interesting is the slur on the 3rd beat of this measure which causes a crescendo to the next measure as opposed to mm 11 and 31.

M 28

Now one expects the final measure of the “Sarabande” with the tonic. However, the Rel is strongly emphasized with it, the end of the movement is thus delayed. JSB now writes a slur on each of the two sixteenth notes in the 1st and 2nd beats. This causes accentuations of the top note Eb4 and the note Eb3 on the 3rd beat.

It is striking that the bass note C3 on the first beat is a quarter note. The slur on the two sixteenth notes violates to a certain extent the rule of the “Slur-Code”, that all notes in the upper voice are slurred. In addition, the other rule does not apply, that if two slurs follow each other immediately, then the second slur decrescendos. The top note would not be stressed at all if all the notes in the first beat were slurred, as in this case, in direct connection to the slur of the previous measure, here would be a decrescendo. JSB intends, however a strong prominence of the Rel and just the tonic (root Eb5) in this measure. Both harmonies are equal.

The mixing of these harmonics, Rel and tonic, is demonstrated in particular by the pitch Bb3 which is contained in this measure. For the triads of the tonic and the Rel differ only by the pitches C and Bb. The coincidence of the notes Bb3 and C3 signals, in the context of the two notes Eb3 and G3, the dazzling presence of both harmonies. Therefore JSB has not reduced the bass note C3 to an eighth note so that both pitches C3 and Bb3 are heard together, and thus indicates the ambivalent harmonic situation of this measure.

The end of the phrase arrives back on the note Eb3, the root of the tonic or the third of the Rel, which is tied, as in mm 4, 23 and 25f. One last time, this Eb3 is emphasized and reinforces the tonic character at the end of the measure.

Note:

From m 25 a stepwise building crescendo is generated due to the slurs. There is no let-up of the sound intensity until m 29.

*

How was passage has played in the cello competition?

Interpretation of mm 25-28 by the 11 participants

Similar to mm 5f the consistent two voices in the first beats were never heard, in particular the dissonant harmonies of the fourth sixteenth note with the bass, which was regularly shortened to an eighth note. A legato was not played at the dotted rhythms alike, sometimes even the rhythmic impetus was reinforced by over-dotting (32nd notes). A dynamic increase of up to m 28 was rarely heard. Often this measure was conceived as an overtone ornament, as if it were a “triad” of a fundamental.

*

In the following passage which expands the second half of the movement with four final bars the “tone-defining” harmonies are mingled and lose track of harmonic function. But, in spite of everything, the ties make it possible to deliver a consistent picture of the harmonic sequence.

M 29

The note Eb3 still does not imply transition to the tonic but it is here harmonized with the tritone A2. This is reminiscent of m 23, so that the s6-chord can be expected. However, this time the bass note C2 is missing. The note Gb3 then transforms the harmony to a DD9-chord. But again, as in both previous measures, there is a quarter in the lower voice, so that the dissonant sixteenth note Gb3 is slurred to the previous note. This clouds the clarity of the harmonic progression, similar to the slurring of the seventh Ab3 in m 27. In addition, now a decrescendo is generated with the slur, which causes the questioning character or the weakening effect of this twist.

M 30

The top note Eb4 is tied again. The bass descends by semitone from A2 to Ab2. Although with this Ab2 the seventh of a D7-chord is notated. But why did JSB not simply write the usual bass note Bb2? With a bass note Bb2, in conjunction with a quarter note for the chord, the Dom would be unambiguous. This would otherwise be contrary to the tie since the seventh of a SD is never connected to the suspended fourth of the resolution. As such, the bass note Ab2 is not to be interpreted as seventh of the Dom, it does not sound in this way.

These considerations lead to a different interpretation of the harmonic development in this measure. With the half tone movement A2 in the previous measure to Ab2, this time noticeable downwards, we arrive at the SR. It has the same root as the DD in m 29, where the upper Eb4 acts as seventh in both chords which justifies the tie.

Both the upper part and the chord tones differ now from the preceding measures that would be analagous (mm 2, 4 and 22f). The top note is Eb4 already resolves to the sixth and fifth, D4 and C4 in the first beat. The chord tones are therefore reduced to an eighth note so that no slurring occurs in the upper part (a suspension action is not usually bound in the suites to its resolution). The fact that the chord tones shrink to eighth notes thickens the harmony.

This “resolution” or continuation of the seventh Eb4 (seventh chord on the SR) in the sixth d4 causes the s6-chord of the Rel, which is continued to F4, DR with seventh.

The three-part harmony at the beginning of the measure could suggest an S65-chord (Sub with added sixth F3) which has the identical pitch content. But, the overall context, ie the “voicing” is more prone to interpretation as the SR chord with seventh.

Note:

Only the curved bow allows both the tieing of the seventh Eb4 as well as the chord, without leaving the seventh, so that all three notes of the chord can be played together. Nevertheless, a bow change is inevitable, but the upper voice should not be interrupted (3rd beat of m 29 in the up bow and chord in the down bow). The concave bow however has to move from the upper part to the lower voices and causes an interruption on the tied Eb4. This suggests the “other” harmony, the D7-chord with seventh in the bass and Eb4 as suspended fourth. However, this is clearly in contradiction with the notation, ie the “compositional ” tie. In other words, JSB must have had an opportunity to perform these three voices on the instrument.

The seventh chord on the SR can only be realized with the involvement of the left hand thumb. While this case is a game of extreme technique, it is not an isolated case in the “Suites” (see m 11 and “Prélude” in C major).

M 31

The note Bb3 is now tied. It could continue to be heard as a third of the DR, or as fifth of the tonic. In both interpretations there is no difference in intonation because of the fifth relationship Bb3-Eb3. The fact alone that the last tie does not re-trigger an interpretive conflict in terms of an either-or-decision on the prevailing harmony, signifies a relief of the harmonic ambiguity is initiated.

Again, the chord tones have only an eighth note, so that the sixteenth Ab3 can be clearly articulated (dampen the G-string). This pitch does not belong to the DR, but to the tonic. It is certainly no longer appears that the major keys should again gain the upper hand. However, the Rel is not yet completely ruled out.

Now, with the hint of tonic or Rel, the Sub is now clearer after a last appeal to its Rel in the 2nd beat with the note Eb3. Here, the bass note is also shortened so that the note Eb, fifth of the Sub, is not slurred. So there is no preference between the two harmonies. A quarter note Ab2 in the lower voice would give momentum to the SR, because the note Eb3 would then be regarded as a passing note. And now, in the 3rd beat follows either the Dom, or the DR? This remains open.

Note:

Despite the note Ab3 in this pool of harmonies, the DR is still included. The presence of the DR is even highlighted in the first beat of the following measure again. The note Ab3 could then be regarded as a minor ninth suspension over the root G. This semitone Ab-G is answered in the final measure with the semitone resolution D-Eb.

As it happens, the leading tone suspensions are the subject of this movement. In m 27 the suspension Ab3-G3 of the DR has already been addressed. In m 29, the suspension Gb3-F3 can be heard. In m 30 the suspension is Eb4-D4. These half steps derived from the initial motif with suspended fourth (m 2 and m 4), by transferring them to other pitch and function levels (9-8, or 7-6 suspensions).

M 32

After the penultimate measure failed to clarify motion of the relative major and minor keys towards tonic, there follows with a garland of rising sixteenth notes the very last effort to resolve these ghostly harmonic events. In the first beat again the DR appears through (a 3-slur on the note G2, which integrates the fifth Bb2 of the tonic), The harmony now pivots towards principal key by emphasizing the note Eb3 on the 2nd beat (directly adjoining slurs).

These two harmonies, the tonic and DR, are, similar to the tonic and the Rel in m 28, connected by an interval of a second, namely with the notes D and Eb. The note D3 acts as leading note, creating a stress on the 2nd beat and not on the first. These internal dynamics, created by the placement of the slurs, revives the 2 octave ascending line.

Therefore, the second half of the movement does not end with a triumphant tonic sound. Neither is the bass note Eb2 stressed (no slur in the 3rd beat of m 31, but an octave leap down) nor the final high note Eb4, which is achieved with a decrescendo.

Conclusion:

The last 4 bars show in intensified form the ambiguous harmonic progression. While in m 29 the DD with its ninth is still relatively clear, in m 30 an episode suddenly begins with the tieing of the high note Eb5 and the chord which is so multi-layered that the harmonic complexity can not easily be brought to a common denominator, in the sense that unambiguous chords cannot be determined.

While it is obvious, these bars can be ascribed to the harmonic progression DD9-D7-T which many analysts**) do. This superficial harmonic analysis does not thoroughly describe the end of the “Sarabande”. The two ties also clearly thwart this simple interpretation. It can not be assumed that JSB comes to such a banal conclusion after all these harmonic excursions.

The second part of the movement is more prone to the darker, deeper registers in the minor keys. Only in the final measure does Eb major resurface.

*

How was this passage played in the cello competition ?

Interpretation of the mm 29-32 by the 11 participants

The same applies as in the four previous measures, because no cellist realized the coincidence of the ninth Gb3 with the bass note A2 in the first beat of m 29. Some cellists simulated the ties of the upper voice in mm 29ff by playing only the two bass notes of the chords without sustaining the upper voice. Others, however, arpeggiated the chord, so that the upper part was played twice. Thus, these measures were aligned with those that include a suspended fourth. The final measure was regular started with an emphasis (and a tenuto) on the bass note. Some added an ornament to the final note Eb4.

*

Polyphony with the Curved Bow

Although the interpretation of this movement is possible with the today’s commonly used concave bow, the curved bow has great advantages at central points of the composition, eg in m 21, where the bass A2, the third of DD, finally appears for the 1st time, can be fully sustained with the curved bow for a quarter note. The same applies to the root C2 of the s6-chord in m 23. The ties and chords in mm 29ff can only be performed in the notated form with the curved bow.

The advantage of the curved bow is also heard in the chord progression of the m 15, the chord tones can be heard simultaneously and so gain clarity. In the harmonically ambiguous chords in mm 6, 16 and 18 the curved bow allows the simultaneous performance of two harmonies for their full duration of a dotted eighth note.

Similarly, the curved bow is sonically preferable in those places where there is in the upper voice of a chord a suspended note that resolves in the next beat (mm 2, 4 and 22f ), because the bass notes can be sustained, which strengthens the suspended dissonance.

Last but not least, the curved bow is advantageous in all two-voice passages because it facilitates playing technique, because the flexible nature of the bow hair allows a more even sounding of two tones.

JSB’s polyphonic notation cannot be clearer.

The quarter notes in the lower parts of mm 2, 4 , 9, 22f , 25 and 28 signify a clear harmonic situation and require a melodic design of the upper part as a result of the slurring of sixteenth notes.

The sixteenth notes in the upper voices of mm 10f and 26-29 are perceived only as dissonant, but only if they sound simultaneously with the quarter note in the lower voice.

The dotted eighths in mm 6f , 14, 16 and 18 illustrate a harmonically ambivalent situation. The following sixteenth then sounds separately and therefore as a chord tone (and not as a passing note or suspension).

The Ties

Ties in JSB are important clues to understanding the underlying harmonies. In particular, this applies to measures 23f and 29f, which are widely interpreted as Dom In reality they are marked as Sub.

In m 23 the chord C2-A2-Eb3 is not intended to be a DD7-chord which resolves to the Dom In this case, the note Eb3 would first be seventh of the DD and then the suspended fourth over the Dom The note Eb3 should not be tied in this interpretation. But JSB uses a tie, indicating that it is instead the s6-chord, whose presence in the first beat of the following measure is prolonged. This suggests that with these ties those pitches are connected, which are at the same time chord tones in both harmonies and identical in pitch.

Frequencies of pitches connected by ties

M 4f

The tonic is initially retained, the note Eb3 is its third. That is, the harmony does not change.

M 6f

The note Db4 is construed in m 6 as the seventh of the tonic and in m 7 it becomes the ninth of the Dom of the DD. Here the tritone G3-Db4 in both chords is identical and thus the pitch Db4.

M 9ff

No matter what chord progression is assumed (Dom-tonic-Dom (DD) or DD Rel -DR – DD Rel), the pitch Bb3 remains, whether it is the key note or a fifth, unchanged.

Calculation based on D3 : 8/5 – 16/ 15 x 3 /2 = 8/5 – 6/ 5 x 4 /3 = 8/5

Calculated based on Bb2 : 2 – 4 /3 x 3/2 = 2 – 3/2 x 4/3 = 2

M 13f

Same situation as in m 6f : the seventh becomes the ninth.

M 18f

Analogous to mm 9ff is the note C4 once root (Rel) , then (SR) and remains unchanged.

M 23f

The harmonic development in m 24 is unclear. The continuation of the s6-chord is on the 1st beat of m 24 is still open, the bass note Bb2 being a passing note. The harmony initially does not change (see m 5). Therefore, the note Eb3 remains unchanged.

M 25ff

Here the same applies as in mm 9ff.

M 28f

The tritone causes the s6-chord to be expected again as in m 23, i.e. that the frequencies of the third of the Rel and of the third of the s6-chord are identical.

M 29f

The note Eb4 is now the seventh of the DD and of the SR. Both have the same root, and consequently the same seventh.

M 30f

Again, the harmonic situation is ambiguous. The tie is justified in all harmonic interpretations. Either the DR is retained across the bar line, or a modulation from the Dom to the tonic occurs instead. Then Bb3 would be the keynote of the Dom or the fifth of the tonic, in both cases the pitch is identical.

Frequencies of those pitches that are decidedly not connected by ties

M 1f

As shown in the analysis, here is a clear resolution of the SD with seventh Db4 to Sub with suspended fourth Db4. The two pitches are not identical.

M 3f

Again, the resolution of the seventh of the Dom to the suspended fourth of the tonic takes place.

M 5f

Again, with the descending fifth in the bass a resolution with suspended fourth in the upper voice is simulated.

M 15f

The same applies across this bar line.

M 21ff

These bars are similar to mm 1 and 3

In other words, every time a SD seventh is turned into a suspended fourth over the harmonic resolution, there is no tie. To take up the metaphor of Thomas Mann (see analysis of the “Prelude” in G major) again , “Servant tones” obviously are not connected to “Master tones”. Because the suspended fourth does not constitute pitch of the chord of resolution.

Comparison with other manuscripts

It might be of interest, to compare with the other three surviving copies from the 18th century. As for the slurs, these copies are generally much too vague and arbitrary, to be amenable to analysis. In rare cases they can be used to identify pitches.

All copies add ties and as desired additional trills and suspensions. The note durations were not given the attention they deserve by Johann Peter Kellner.

Source B (Kellner)

In mm 3, 8, 13 and 19 trills are added.

Different note durations can be found in m 6 (lower voices eighth note), m 13 (lower voice dotted half note), T 15 (lower voices eighth and dotted eighth notes), m 18 (lower voices eighth note) and m 24 (lower voices dotted eighth note) .

Ties are lacking in the mm 13f and 30f. Additional ties were added in the mm 14f , 21f and 22f .

Slurs are missing in m 2 on the sixteenth notes, in m 27 in the 3rd beat and in m 28 on the first beat.

Source C

In mm 1, 3, 13, 19 trills are added, as well as suspension marks in mm 2, 4, 14, 17 and 20.

The note durations are all correct, except for the dotted half note in the lower part of m 13.

Ties are added to mm 21f and 22f.

A slur is absent in m 14.

The same applies to Source D.

It appears unmistakably in a direct comparison with these other transcripts, that only the AMB mamnuscript can be considered to be authentic.

*)

Cello-Competition for New Music and award of the Domnick Cello Prize

Staatliche Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst Stuttgart, Germany

January 20-25, 2014

The Participants:

Charles-Antoine Duflot

Raphael Moraly

Armand Fauchère

Magdalena Bojanowicz

Darima Tcyrempilova

David Eggert

Hugo Rannou

Minji Won

Beatrice Holzer-Graf

Hanna Magdaleine Kölbel

Jee Hye Bae

Examples from Secondary Sources

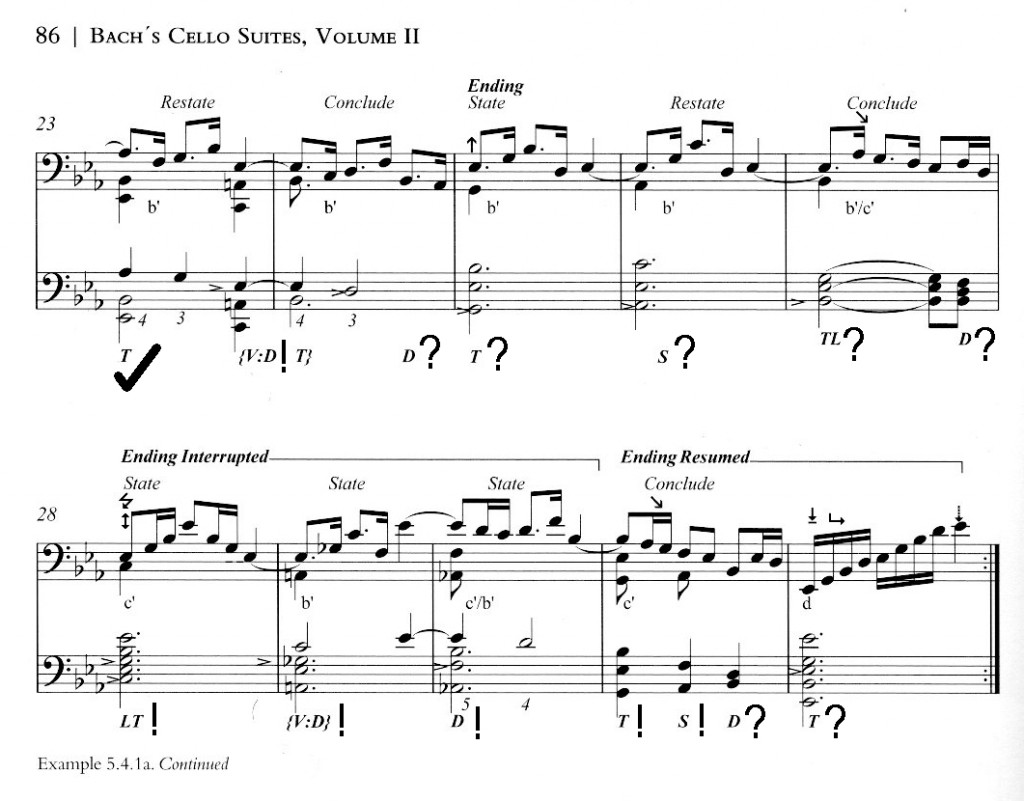

Allen Winold, “Bach’s Cello Suites“, Indiana University Press, Bloomington 2007 Allen Winold,

musical examples mm 23-32 (Exclamation marks, question marks and hooks added)

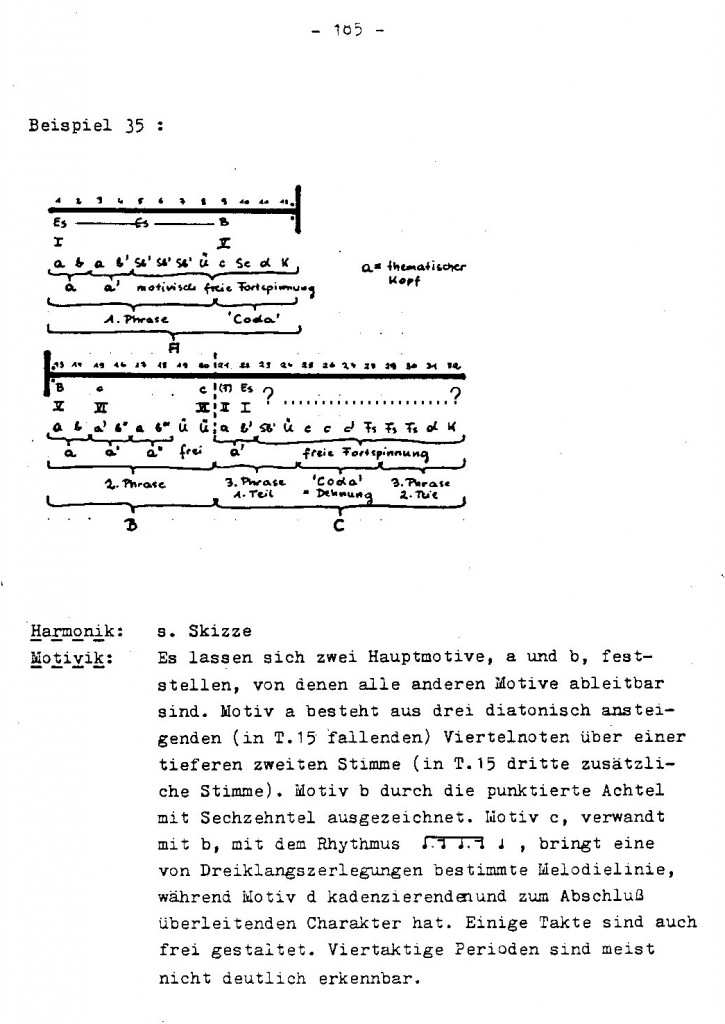

Ingrid Fuchs, “Die Sechs Suiten für Violoncello solo“, Diss. Wien 1980 Ingrid Fuchs,

harmonische Skizze der Sarabande in Es-Dur (questions marks added)