23.12.1906 – 20.07.1998

Sein Rundbogenspiel. Seine Bachinterpretation.

Tossi Spiwakowskis Artikel über die Solowerke für Violine von J. S. Bach 1) aus dem Jahr 1967 war mir durch Rudolf Gählers Buch, Der Rundbogen für die Violine – ein Phantom? 2) bekannt und auch die Tatsache, daß Spiwakowski einen Rundbogen, den VEGA BACH BOW des dänischen Geigenbauers Knud Vestergaard verwendete, der ursprünglich für den Geiger Emil Telmányi (1892 – 1988) entworfen wurde. Bedauerlich war aber, daß bislang keine einzige Tonaufnahme mit Spiwakowski und dessen Rundbogen aufzutreiben war. Mehr oder weniger zufällig gelang es mir, Kontakt mit der Fotografin Ruth Voorhis, der Tochter von Spiwakowski, aufzunehmen und erhielt von ihr einige Fotografien von dessen VEGA BACH BOW zugesandt, sowie die Information, daß ein Live-Mitschnitt der Chaconne, gespielt von Spiwakowski mit dem Rundbogen, gerade veröffentlicht wurde 3).

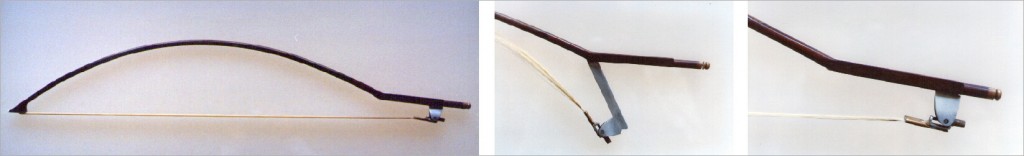

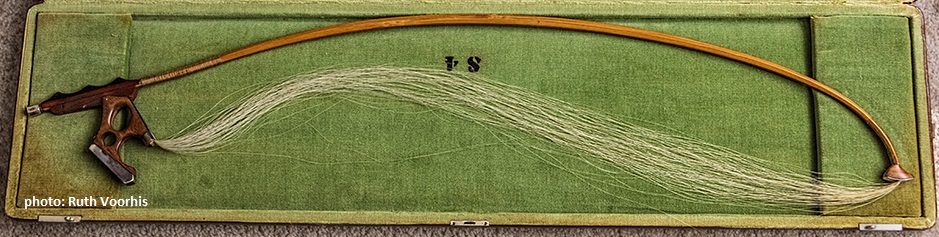

Ich kenne diesen VEGA BACH BOW (Abb. 1) seit Anfang der 90er Jahre genau, da Rudolf Gähler ein Exemplar in seiner Sammlung beherbergt. Eine detaillierte Dokumentation dieses Rundbogens wird auf der ungarischen Website https://www.vonokeszites.hu/de/bogen/emil-telmanyi bereitgestellt.

Auffallend war für mich, daß der Rundbogen Spiwakowkis sehr starke Gebrauchsspuren aufweist, was für mich die zweifellos beträchtliche Bedeutung dieses Rundbogens für ihn aufzeigt. Hier müssen sich heroische Kämpfe in der Bezwingung dieses Bogenwerkzeugs abgespielt haben. Zweitens, Spiwakowski hatte den Arretiermechanismus ausgebaut 4), welcher eigentlich dafür gedacht ist, den Daumen im einstimmigen Spiel und den damit einhergehenden hohen Zugkräften der Bogenhaare zu entlasten. Diese Elimination des Einrastmechanismus ist für mich ein deutlicher Hinweis dafür, daß Spiwakowski herausfand, daß derartige Mechanismen für die Entlastung der Muskeln umständlich zu handhabend sind, letztendlich doch eher eine spieltechnische Barriere bedeuten, also kontraproduktiv sind. Denn jedwede zusätzliche Apparatur, die die Unmittelbarkeit des Spielvorgangs behindert, minimiert die Kontrolle über die sensiblen haptischen Bewegungsabläufe. Ich selbst erkenne in einem solchen Hilfsmechanismus ein Indiz für eine nicht ausgereifte Konstruktion und sehe mich durch Spiwakowski darin bestätigt, daß mechanische Hilfen genauestens auf ihre Zweckmäßigkeit untersucht werden sollten und sich in der Praxis beweisen müssen.

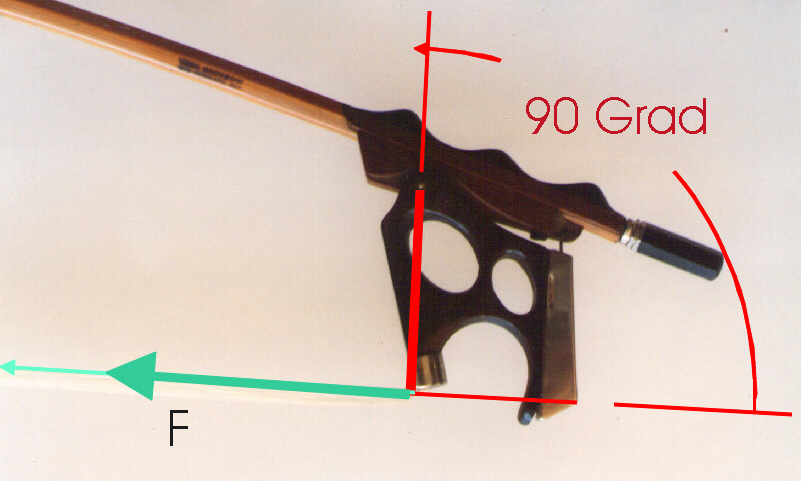

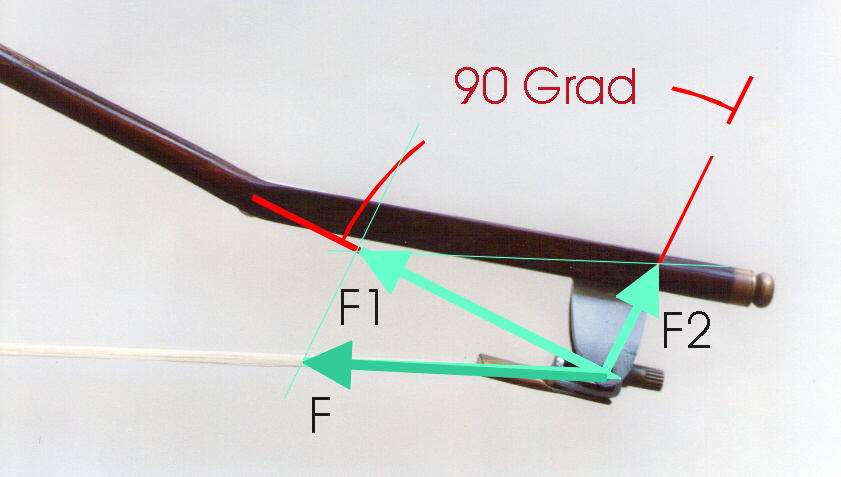

Dieser unvorteilhaft große Kraftaufwand, die der VEGA BACH BOW erfordert, rührt daher, daß der Hebel relativ kurz ist (Abb. 2) und seine Position bei gespannten Bogenhaaren einen Winkel zu den Haaren von etwa 90 Grad aufweist. Beide geometrischen Charakteristika, die physikalisch dazu führen, daß die rechte Hand des Geigers kräftemäßig über Gebühr belastet wird, sind eigentlich unüberbrückbare Hindernisse. Die Griffmulden auf der Oberseite des Griffs sind zusätzliche Behelfe, um die Hand trotz dieser Kraftanstrengungen in Position zu halten. Um die Probleme für die rechte Hand zu verringern, ist es für den Konstrukteur jedoch erforderlich, nicht symptomatisch vorzugehen, sondern zunächst die ursächlichen Prinzipien zu verstehen und dann geeignete Lösungen zu finden. Der Frosch des VEGA BACH BOW hat noch eine weitere Öffnung für den Daumen, damit das einstimmige Spiel im arretierten Zustand des Frosches erleichtert wird. Der Daumen wechselt also während des Spiels zwischen zwei Positionen, was eine abermalige Erschwernis darstellt. Zu den nachteiligen Eigenschaften des Griffs kommt hinzu, daß die Bogenstange in der oberen Hälfte, also von der Mitte bis zur Bogenspitze hin, eine hohe Wölbung beibehält. Somit sind zwar vierstimmige Akkorde über die gesamte Länge des Rundbogens spielbar, der Schwerpunkt liegt aber dementsprechend hoch, so daß das einstimmige Spiel zusätzlich erschwert wird.

Diese konstruktiv bedingten Nachteile tauchen bei dem konkurrierenden Rundbogenmodell (Abb. 3) von Rolph Schroeder (1900 – 1980) weit weniger auf, da der Hebel zum Spannen und Entspannen der Haare länger ist. Gemäß dem Hebelgesetz reduziert dies den Kraftaufwand, verlängert aber die Distanzen für den Daumen. Doch dies ist kein wirkliches Manko, wie die Spielpraxis aufzeigt. Zweitens, im gespannten Zustand wird der Hebel in den Griff eingeklappt, so daß der Drehpunkt des Hebels einen Anteil (F1) der Zugkräfte (F) im einstimmigen Spiel aufnimmt (Abb. 4). Telmányi, der seinerseits das Rundbogenspiel in den 30er Jahren von Schroeder vorgeführt bekam, konnte leider nicht dessen Prototyp erstehen, so daß er damals auf eine eigenständige, neu entworfene Konstruktion angewiesen war. Spiwakowski hingegen kannte seinerseits alleinig nur den Rundbogen von Telmányi und hatte kaum eine andere Wahl, als damit zu operieren. Gewissermaßen war es für ihn einfacher und rascher, sich im Jahr 1957 von Vestergaard einen VEGA BACH BOW zu besorgen, als eine zeitaufwendige Neukonstruktion mit ungewissen Ergebnissen zu versuchen.

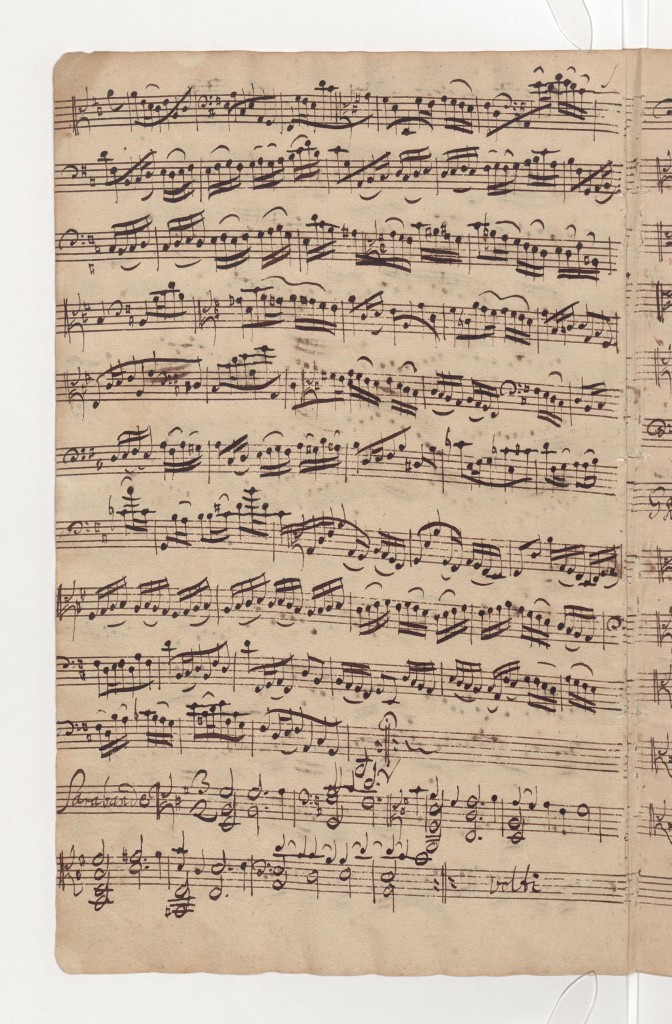

Ich erinnere mich, als ich im Jahr 1990 erstmals die Aufnahmen der Rundbogenspieler Rolph Schroeder, Emil Telmányi und Otto Büchner (1924 – 2008) von Rudolf Gähler vorgeführt bekam, wie mich allein schon dieser mehrtönige Klang der Geige faszinierte. Trotzdem sind Telmányis Schwierigkeiten der Beherrschung dieses sehr extrem ausgeformten VEGA BACH BOW in seinen Bachaufnahmen von 1954 unüberhörbar. Insofern war ich äußerst gespannt auf die neuerliche Veröffentlichung des Mitschnitts des Schwedischen Rundfunks aus dem Jahr 1969 mit Tossi Spiwakowskis Interpretation der Chaconne. Die Überraschung war perfekt, denn aufgrund dieses Tondokuments möchte man meinen, daß Spiwakowski ein anderes Rundbogenmodell zur Verfügung gehabt hätte. Fast nichts von den enormen spieltechnischen Problemen, die dieser VEGA BACH BOW aufwirft, ist bei seinem Spiel konstatierbar. Diese Leistung Spiwakowskis als eine Selbstverständlichkeit zu goutieren, ist für mich unvorstellbar. Die Zuhörer Spiwakowskis müssen regelrecht vom Stuhl gefallen sein, bei einem so meisterlichen Vortrag der Chaconne mit dem Rundbogen.

Michael Bach

1) Tossy Spivakovsky, Polyphony in Bach’s Works for Solo Violin, published in 1967 in The Music Review, Vol. 28, No. 4

2) Rudolf Gähler, Der Rundbogen für die Violine – ein Phantom?, Conbrio Verlag, Regensburg 1997

3) Live-Mitschnitt, Schwedischer Rundfunk, Stockholm, 26. Januar 1969, DOREMI DHR-8025-8

4) siehe Foto: Tossi Spiwakowski, Einführung zur Interpretation von J. S. Bachs Solowerken für Violine mit dem Rundbogen