Michael Bach

Dies ist der dritte Teil der Transkription meiner Präsentation „Urtext = Klartext?”

vom 4. Mai 2013 in der Stiftung Domnick in Nürtingen bei Stuttgart

Anmerkung: Es ist hilfreich, parallel ein zweites Browserfenster zu öffnen mit dem Blogbeitrag “Die Bindebögen im Prélude der Suite in G-dur für Cello solo” https://www.bach-bogen.de/blog/thebachupdate/die-bindebogen-im-prelude-der-suite-in-g-dur um den Notentext direkt vor Augen zu haben.

Glossar:

JSB = Johann Sebastian Bach

AMB = Anna Magdalena Bach

2-B, 3-B, 4-B = Bindebogen über 2, 3 oder 4 Noten

drei 2-Bn = drei Bindebögen über 2 Noten

1. Zz = 1. Zählzeit eines Takts

c4 = c’

DD = Doppeldominante

D7-Akkord= Dominantseptakkord

D9-Akkord = Dominantnonakkord

Die Ausdrücke “Herrenton” und “Dienerton” sind dem Roman “Doktor Faustus” von Thomas Mann entlehnt. Sie unterscheiden zwischen akkordeigenen Tönen und nicht akkordeigenen Tönen, wie Wechselnoten oder Durchgangstöne. Näheres hierzu in Teil 1 der Analyse.

[spielt Takt 19]

Hier ist nochmals das fis2, das weiter in die Tiefe führt … jetzt das cis2, ein 3-B …

[spielt weiter bis zum Ende des Takt 20 und spielt sodann die denkbare Auflösung nach D-dur]

Ich habe jetzt einmal die Auflösung [zur Dominante] dieses Spannungsakkords [DD7-Akkord] mitgespielt, das passiert hier aber nicht, … aber um deutlich zu machen, warum hier ein Bindebogen „fehlt”. Ein Bindebogen …

[spielt Anfang von Takt 20]

… ist auf der Note a2 [3-B], betont die Septim g3 des DD7-Akkords, und dann kommt kein Bindebogen in der 2. Takthälfte [in der Wiederholung des Motivs] …

[spielt 2. Takthälfte]

… das ist eine Abschwächung [Entspannung], und jetzt kommt aber nicht die Auflösung, die man erwartet …

[spielt den Dreiklang von D-dur]

… sondern anstatt daß JSB von dem cis2 einen Halbton höher geht [zur Quint d2 des auflösenden Dominant-Akkords], geht er jetzt einen Halbton tiefer:

[spielt cis2 und dann c2]

Das ist die Septim c2 desjenigen Auflösungsakkords [D-dur], der jetzt eigentlich kommen müßte. Die Tatsache, daß JSB keinen Bindebogen in der 2. Hälfte von Takt 20 geschrieben hat, bedeutet daß er zunächst einmal uns glauben machen möchte, daß jetzt eine Auflösung kommt. Die Urtextausgaben ergänzen natürlich „brav” hier den Bindebogen – in der 2. Takthälfte.

Anmerkung: Was hätte JSB denn tun müssen, um unmißverständlich deutlich zu machen, daß er keine Wiederholung des 3-B wünscht? Etwa ein schriftlicher Vermerk über den Noten: „Hier ist kein Bindebogen” ? Gleiches betrifft auch die Takte 3, 8, 24 und 39-41, in denen die Urtextausgaben meist Bindebögen ergänzen.

Jetzt aber, in diesem Takt 21 sind alle Bindebögen an ihrer Stelle:

[spielt Anfang von Takt 21]

Wieder die Note a2, welche den 3-B erhält. Das ist schon so etwas wie ein Orgelpunkt. Die Terz fis3 wird betont:

[spielt die Takte 21 und 22 bis zur Fermate]

Ja, also die Bindebögen immer auf der Note a2 bilden so etwas wie ein Orgelpunkt. Es ist der einzige Ton der beiden Harmonien [Dominante und DD] angehört, …

[spielt Takt 20 und 21]

… der identisch ist. Was jetzt geschieht, ist etwas ganz Besonderes, und zwar in diesem Fermatentakt [Takt 22]:

[spielt 1. Hälfte von Takt 22]

… dieses cis4, weil es paßt hier gar nicht rein. Wir haben ja hier einen D7-Akkord, so:

[spielt den D7-Akkord]

… der müßte sich nach G-dur auflösen:

[spielt Dreiklang von G-dur]

JSB “bastelt” hier aber die Note cis4 rein. Und die Frage stellt sich: Was ist das denn hier? Ist es ein Herren- oder ein Dienerton? Also man könnte jetzt auch vermuten, daß er hier eine Zwischendominante nochmal einbringt:

[spielt den DD7-Akkord mit cis4 und den Dominantakkord als Auflösung]

Aber wir sind ja bereits in der Dominante [Takt 21], dann eine kurzzeitige Zwischendominante [16tel-Note cis4 in Takt 22] und dann wieder die Dominante [Note d4 mit Fermate] … das macht wenig Sinn, dieser Aufwand lohnt sich hier nicht. Außerdem ist die Zeitspanne [nur eine 16tel-Note cis4] auch viel zu kurz, um hier eine Zwischendominante einzufügen, die wahrgenommen werden könnte. Und: Das cis4 ist eingebunden [also unbetont]. Wir haben hier einen Bindebogen …

[spielt 2. Zz von Takt 22]

… sogar das d4 ist noch angebunden. D. h., daß JSB hier, ja, …, eine Irritation schafft, mit diesem Halbton cis4, und daß diese Passage wie eine Frage endet. Viele Interpreten sehen das anders und meinen, man könnte noch eine Verzierung auf die Note cis4 setzen:

[spielt 2. Zz von Takt 22 mit Mordent auf der Note cis4 und betont die Spitzennote d4 mit einem Abstrich]

… und das d4 als Abschluß spielen. Mit einer Verzierung würde man auch die Note cis4 mindestens einmal wiederholen. Aber meiner Meinung nach soll sie eigentlich nur im „Vorbeigehen”, sozusagen „en passant”, erscheinen. Sie soll nicht zu deutlich akzentuiert werden, weil, es geht gleich weiter:

[spielt die ersten drei 16tel-Noten nach der Fermate]

… und da haben wir wieder ein c3. Wir befinden uns immer noch im D7-Akkord:

[spielt den D7-Akkord]

… und haben ihn nicht verlassen. Dieses cis4 ist sozusagen ein melodisches Element, was, später am Satzende [Chromatik], zu einer grandiosen Auswirkung kommt.

Anmerkung: Im Anschluß an das Seminar hatte das Publikum die Möglichkeit, Fragen zu stellen. Dieser Takt wurde nochmals aufgegriffen und alternative Fassungen für die Tonhöhe cis4 demonstriert.

Es ist noch etwas Besonderes, und zwar wir haben 2 Bindebögen, die einander direkt folgen. Das bedeutet in meiner Interpretation, daß – wie bei einem Bindebogen sowieso: [spielt 1. Bindebogen des Takt 22 und die anschließende Note a3] … die dem Bindebogen folgende Note betont ist. Das bedeutet weiterhin, daß ein decrescendo in der 2. Zz stattfindet:

[spielt 2. Zz von Takt 22]

D. h. es wird nicht das d4 …

[spielt d4, den Spitzenton von Takt 22]

… als Abschluß betont. Sondern diese Note ist angehängt. Wenn also 2 Bindebögen einander folgen, dann hat es meistens zum Resultat, daß der 2. Bindebogen einen Akzent bekommt und decrescendiert, also im weiteren Verlauf leiser wird. Wir haben nochmals eine solche Stelle in diesem Satz, die das bestätigt. Ja, noch etwas: Viele Analysten sehen hier den Schluß des 1. Teils des Préludes und denken, daß jetzt die 2. Satzhälfte anfängt. Das ist aber nicht so. Die 2. Satzhälfte fängt natürlich … [spielt Anfang von Takt 19] … mit dieser Tonika an und führt zu diesen beiden Harmonien, die uns jetzt die ganze 2. Satzhälfte lang begleiten werden.

Anmerkung: Auffällig sind die beiden Baßnoten cis2 und c2 der Takte 20 und 21, zwei Tonhöhen, die beide Harmonien klar trennen: cis2 als Terz der DD und c2 als Septim der Dominante. Sowohl der stetige Wechsel zwischen c4 und cis4 als auch der doppelte Orgelpunkt d2-a2 ist charakteristisch für die 2. Satzhälfte.

Wir haben immer den Orgelpunkt d2 und a2:

[spielt die Quint d2-a2]

Das d2 steht für die Dominante und das a2 für die DD [wobei sie auch als Quint der Dominante angehört]. Und so geht es in Takt 22 [nach der Fermate] weiter, es fängt mit einem a2 an:

[spielt die aufsteigende Skala von Takt 22 mit a2 beginnend bis zum Beginn von Takt 24]

Hier sind keine Bindebögen, warum? Weil die Harmonie hier klar ist. Es gibt keinen Zweifel, es ist alles in der Dominante mit Septim. Aber, was jetzt im übernächsten Takt geschieht:

[spielt Takt 24 mit Auftakt d4]

… da passiert zum ersten Mal eine halbtönige Ausweitung des Tonraums, nämlich zum es4. Das ist die None dieses Akkords der Dominante:

[spielt die Akkordtöne der Dominante und betont die Septim c4 und die None es4]

Septim, None, das ist also die kleine Tonraumerweiterung. Jetzt sind wir also auf der None gelandet, man bemerkt dieses halbtönige Umspielen der Note d4, die der Spitzenton bislang war, …

[spielt 1. und 2. Zz des Takt 24]

… dieses vorübergehende Entsetzen, das JSB nun selbst gepackt hat, daß er jetzt nun über diesen Tonraum hinweg gegangen ist, so daß er die Note d4 ganz „ängstlich” umspielt, und jetzt …

[spielt weiter bis zum Ende von Takt 24]

… kehrt er schnurstraks zurück auf sicheren Grund, den Grundton:

[spielt weiter bis zur 2. Zz von Takt 25]

Das ist die Dominante, die sich mal kurz auflöst …

[spielt weiter bis zum Ende von Takt 25]

… zur Tonika. Das ist aber keine richtige Auflösung, sondern das soll in erster Linie etwas bewirken, nämlich das:

[spielt Takt 26 und betont die Noten g3 und cis4]

Die Note g3 und die Note cis4:

[spielt zunächst g3 und cis4, dann die 2. Takthälfte]

Dieser Tritonussprung macht uns natürlich die DD klar. Jetzt setzt JSB aber einen 2-B auf die Note h3, dadurch wird auch die nachfolgende Note b3 betont. Wir sind da einen kurzen Moment in einem harmonisch ungesicherten Raum, weil die DD, die wir hier haben:

[spielt den DD9-Akkord]

… hat die Note b3 als None, die sich nach a3 auflöst. Hier haben wir aber zunächst ein h3, das ist zwar eine leitereigene Tonhöhe:

[spielt die Tonleiter von A-dur]

… also melodisch „richtig”, aber harmonisch „falsch”, wenn Sie so wollen. Und deshalb setzt JSB einen 2-B auf die Note h3, damit man sie deutlich hört.

Anmerkung: Diese Reibung zwischen h3 und b3 ist besonders dissonant und ausdrucksstark.

Die Urtextausgaben machen daraus einen 3-B:

[spielt die Version der Urtextausgaben mit einem 3-B auf der Note cis4]

Anmerkung: Dadurch bleibt die Note h3 ein unbetonter Dienerton der DD, was die Dissonanz, die halbtönige Abfolge, abschwächt.

Manche Editionen ändern sogar noch die Note h3 zu b3:

[spielt cis4-b3-a3-b3]

Damit ist harmonisch „alles klar”, da gibt es keine Irritation. Aber in dieser Version schon:

[spielt cis4-h3-a3-b3]

Anmerkung: Ein Kuriosum am Rande: JSB hätte mit der Tonhöhe c4 anstelle von cis4 die Buchstaben seines Namens CHAB zitiert. Die harmonische Irritation mit cis4, h3 und b3 war ihm aber wichtiger als das Namenszitat.

Also es sind hier 2-Bn: [spielt 2. Hälfte von Takt 26 mit 2-Bn auf den Noten h3 und a3] Damit wird, wie gesagt, auch die Note b3 und der Grundton a3 betont. Und jetzt auch die Septim g3:

[spielt weiter bis zum Ende von Takt 27 mit 3-B auf g3 in der 1. Zz]

Anmerkung: Unerwähnt blieben im Vortrag die stabilisierenden 3-B in Takt 25 auf der Note a2, in Takt 26 auf der Note g2 und in Takt 27 auf der Note cis3, die jeweils den Grundton der DD und der Tonika, sowie die Terz der DD akzentuieren.

Die Auflösung zur Tonika in Takt 26 bewirkt eine Kräftigung des Grundtons g3, der aber umgedeutet wird zur Septim der DD.

Jetzt erscheint das cis4, das im Fermatentakt eingeführt wurde, ein letztes Mal, oder ein vorletztes Mal, denn es wird wiederholt, als Leitton [und Wechselnote] zum d4.

[spielt cis4-d4-cis4-d4]

Wir sind jetzt ziemlich eindeutig in D-dur gelandet: [spielt Takt 28 bis zur Note d2] So, das ist wieder der Orgelpunkt d2 [Pause]. Ich würde jetzt vorschlagen, ich bin zwar „gut in Fahrt” [Lachen im Publikum], aber es wird nochmals hier einen ziemlichen „Brocken” geben, der geknackt werden muß, und das wäre jetzt ein wenig zu viel, ich denke wir brauchen noch ungefähr eine halbe Stunde, wenigstens, bis wir am Ende sind. Ich würde gerne eine kurze Pause machen [Applaus].

[nach der Pause]

Ich möchte noch etwas nachtragen, ich habe das Ganze ja ohne Manuskript gehalten. Eine Kleinigkeit zu den letzten beiden Stellen, die wir gehört haben. Die Urtextausgaben gleichen die beiden Stellen einander an, diese:

[spielt zunächst vorbereitend den Takt 23]

Die Urtextausgaben machen daraus einen 3-B: [spielt Takt 24 mit jeweils einen 3-B auf den Noten es4 der 1. Zz und d4 der 2. Zz] … und genauso auch hier:

[spielt Takt 26 mit jeweils einen 3-B auf den Noten cis4 der 3. Zz und b4 der 4. Zz]

Das steht natürlich nicht da. Warum? Die Stellen ähneln sich zwar, sie gehen auch beide auf diesen Fermatentakt zurück:

[spielt 2. Zz von Takt 22]

… wo diese Chromatik bereits angedeutet wird. Aber in Takt 24 passiert alles in einem harmonisch gesicherten Raum:

[spielt Beginn von Takt 24]

Es geschieht nur eine ganz kleine Tonraumerweiterung zur None hin, mehr nicht. Währenddessen in diesem Takt:

[spielt die 3. und 4. Zz von Takt 26]

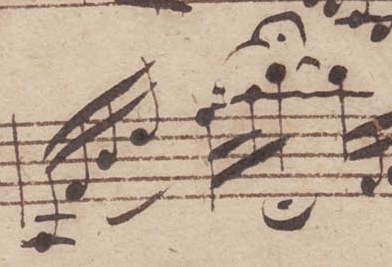

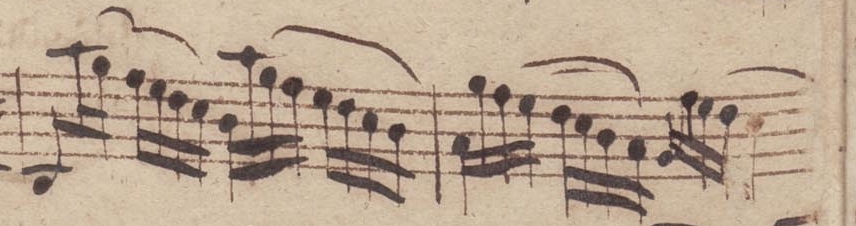

… für einen Moment lang die Harmonie destabilisiert wird. Deswegen die Bindebögen auf denjenigen Noten, die das bewirken. Jetzt kommen wir zu einer Stelle, – und ich versuche nun, mich etwas mehr an das Manuskript zu halten, – wo nur … die Artikulation … uns auf die Fährte bringt, … was harmonisch gemeint sein kann. Es ist nämlich so, wir haben zum ersten Mal 4 lange Bindebögen, was schon außergewöhnlich ist. Und, na ja, ich spiele Ihnen zunächst einmal meine Version:

[spielt Takt 29 bis zum Beginn von Takt 31]

So klingt diese Passage.

In dieser Passage von 2 Takten würde man zunächst denken, AMB hat sich hier drei- oder viermal verschrieben … , daß die Bindebögen eigentlich alle gleich sein müßten. Also das Ende dieser Bindebögen ist immer eindeutig, bis auf den letzten, da hat AMB wegen eines Zeilensprungs vergessen, in der nächsten Zeile darunter, den Bindebogen fortzuführen. Das ist ganz eindeutig so, weil am Zeilenende darüber der Bindebogen ganz weit über das Notensystem hinausgeführt ist. Aber er wird nicht in der nächsten Zeile fortgeführt. Also, da ist offen, wo er endet, aber die anderen 3 Bindebögen enden immer am Ende der 2. oder 4. Zz [oder doch nicht?, s. u.]. Nun, was haben wir denn hier eigentlich? Wir haben eine Tonleiter. Die könnte auch so klingen, wenn JSB sie nicht gebrochen hätte [herunter oktaviert, um sie in den Tonraum d2-c4 zu bringen], klänge sie so:

[spielt Takt 29ff beginnend mit der Baßnote d2 und dann eine absteigende Tonleiter beginnend mit der Spitzennote c7]

Sie sehen also, das ist ein riesiger „Berg”. Aber weil das eine Tonleiter ist, können Sie Diener- und Herrentöne eigentlich gar nicht detektieren. D. h., die Harmonie bleibt ungeklärt. Und weil dies so ist, könnte man sagen, warum dann überhaupt Bindebögen? Ich spiele anfänglich den Orgelpunkt d2 einmal mit:

[spielt im détaché Takt 29, wobei in der ersten Takthälfte die Note d3 als Zweitstimme mit erklingt, und hängt den Folgetakt an]

Man könnte die Bindebögen auch weglassen. Aber: Bindebögen haben bei JSB immer etwas zu bedeuten. So bin ich also wieder auf die harmonische Suche gegangen. Es liegt nahe, daß diese Spitzentonhöhen:

[spielt die ersten drei 16tel-Noten der 1. und 3. Zz von Takt 29f]

… also die Tonhöhen nach dem Intervallsprung, sich auflösen, daß sich z. B. die Septim c4 nach h3 auflöst. Und so habe ich mir einmal verschiedene Harmonisierungen ausgedacht. Zunächst sieht es so aus, als ob wir folgendes haben: [spielt Doppelgriffe fis3-c4, gefolgt von den Terzen g3-h3, fis3-a3, e3-g3 und d3-fis3] Das ist eine einfache Harmoniefolge von dem D7-Akkord über die Tonika, Dominante und Tonikaparallele bis zur Dominante. Es könnte aber auch so klingen:

[spielt die 2. Hälfte von Takt 29 bis zur 1. Zz von Takt 31, mit jeweils einem Akkord auf der dritten 16tel-Note der 1. und 3. Zz: zunächst den Tonika-Akkord, dann die Akkorde der Subdominantparallele, der Tonikaparallele und der Dominante]

Darin wäre auch die Tonikaparallele am Ende enthalten, in dem letzten Beispiel davor auch noch die Subdominantparallele. Das gab es bereits im 1. Teil des Préludes [Takt 12], a-moll als Vorstufe zu e-moll. Oder, es könnte so gehen:

[spielt den Tritonus fis3-c4, dann g3-h3, c3-e3, fis3-a3, h2-d3, e3-g3, a2-c3 und d3-fis3]

Das ist auch grundsätzlich nicht viel anders. Das bedeutet aber, daß wir tatsächlich genau eine Auflösung auf der dritten 16tel-Note haben, also so:

[spielt nochmals und ergänzt die Auflösungsakkorde zur Tonika, Subdominantparallele, Tonikaparallele und Dominante, jeweils auf der dritten 16tel-Note der 1. und 3. Zz der Takte 29ff]

… was bedeutet, daß da immer der Bindebogen anfängt. Das würde folgendes heißen:

[spielt Takt 29ff, wobei die langen Bindebögen immer auf der dritten 16tel-Note der 1. und 3. Zz anfangen]

Anmerkung: Vorhalte werden in den Suiten in der Regel nicht an ihre Auflösung gebunden.

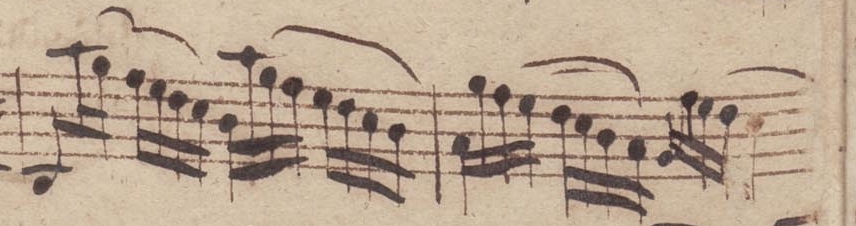

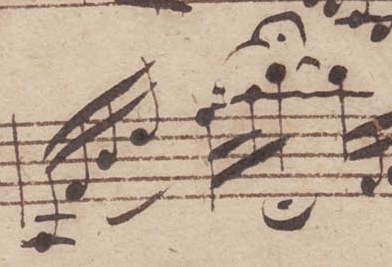

Ich war mit dieser Lösung eigentlich ganz zufrieden … das klingt schlüssig, überzeugend, plausibel … nur, das war mir dann doch zu simpel, und zu liedhaft. Also, es ist nicht deswegen, daß ich mir noch einmal Gedanken gemacht habe, weil ich mit Fehlern in der Abschrift AMB’s nicht leben könnte. Sondern ich habe mir aus künstlerischen Gründen gedacht: „Das ist es wohl doch nicht, weil: warum eine so einfache Harmoniefolge nach diesen ganzen chromatischen Verästelungen? JSB kehrt dazu nicht zurück.” Das war mir klar. Ich habe dann weiter gesucht. Und … ach so, da gibt es noch eine … Ja! … So, wie ich soeben die Bindebögen gesetzt habe, wäre das ja eine Korrektur der Abschrift. Nur der 2. Bindebogen von AMB …

[spielt 2. Hälfte von Takt 29]

… entspricht diesem Schema. Der 3. Bindebogen nicht mehr:

[spielt den Takt 30 mit beiden Bindebögen, die jeweils erst auf der vierten und nicht auf der dritten 16tel-Note beginnen]

Da setzen die Bindebögen eine 16tel-Note später ein. Es ist nämlich so: Der letzte Bindebogen, der unvollständig ist, weil er in der nächsten Notenzeile nicht mehr fortgesetzt wurde, beginnt auf der vierten 16tel-Note:

[demonstriert mit vier Fingern der linken Hand, die die vier 16tel-Noten repräsentieren sollen, und zeichnet den Bindebogen, beginnend mit dem 4. Finger in die Luft]

Man kann aber sehen, AMB hat sich nochmal verschrieben. Sie hat eine Note vergessen. Sie hat eine Note zwischen den ersten beiden 16tel-Noten nachträglich eingefügt und hat die letzte Note [vierte 16tel-Note] ausradiert, so daß man denken könnte, daß sie vergessen hat, den Bindebogen, der zunächst auf der dritten Note zu liegen kam, um eine 16tel-Note nach vorne zu verschieben. Sie hat also den Bindebogen nicht mehr korrigiert, hat das vergessen, – und die Fortführung des Bindebogens in der nächsten Zeile hat sie sowieso vergessen. Also, der führt einfach so ins Leere: [demonstriert mit Händen] Also wäre dieser Bindebogen, selbstverständlich, eine 16tel-Note nach vorne zu versetzen. Der Bindebogen zuvor [Takt 30, 1. Zz] beginnt “leider” auch auf der vierten 16tel-Note. Er sieht aber so aus, daß er gerade [waagrecht, ohne Krümmung] anfängt und hat dann darunter nochmals einen kürzeren Strich, der mißlungen zu sein scheint, weil die Tinte ausgegangen ist oder sonst irgend etwas passiert ist. Der obere Bindebogen wird also nicht nach unten zum Notenkopf geführt, sondern fängt waagrecht an. Dann ist doch plausibel, daß der Anfang des Bindebogens deshalb nicht dasteht, weil der Tintenfluß nicht funktioniert hat. Also verlängert man hier diesen Bindebogen nach vorne bis zur dritten 16tel-Note nach unten. Und damit „ist die Welt in Ordnung”. Was den ersten Bindebogen [Takt 29, 1.Zz] anbelangt, da hat sich AMB definitiv verschrieben, oder es sieht so aus, als ob sie ihn verlängert hat, weil er fängt so an:

[spielt Takt 29 mit einem einzigen langen Bindebogen, beginnend auf der Note h3]

Also tatsächlich auf der vierten 16tel-Note, weil wir hier eine 8tel-Note d2 haben. Oder es sieht so aus, daß sie einen 2-B schrieb, und dann einen 4-B:

[spielt einen 2-B auf der Note h3 und einen 4-B auf der Note a3]

Nun kann aber auf einer einzigen Note [a3] nicht ein Bindebogen aufhören und ein zweiter beginnen. Entweder ist das eine Verlängerung des 4-B nach vorne oder der 2-B ist um eine 16tel-Note nach hinten verrutscht. Letzteres scheint mir an dieser Stelle am plausibelsten zu sein, weil wir die gleichen Tonhöhen im selben Takt [2. Takthälfte] ja nochmals bekommen:

[spielt Takt 29 mit einem 2-B auf der Note c4, einem 4-B auf der Note a3 und den nachfolgenden langen Bindebogen beginnend auf der Note h3 der 3. Zz]

Eine zweimalige Auflösung nach G-dur in diesem Takt macht nun wirklich keinen Sinn:

[spielt Takt 29 mit 2 langen Bindebögen, beginnend auf den beiden Noten h3, jeweils unterlegt mit einem G-dur Akkord]

Das macht keinen Sinn, wenn man das harmonisch denkt. Insofern komme ich zu dem Schluß, daß es ein 2-B ist, der – denken Sie an den Fermatentakt, wo auch 2 Bindebögen einander folgen – bewirkt, daß der 2. Bindebogen stark anfängt und decrescendiert, so daß die Auflösung zur Tonika [3. Zz] tatsächlich entspannt geschehen kann, und das macht für mich auch Sinn: [spielt nochmals Takt 29 mit den 3 Bindebögen] Also, der 1. Bindebogen wäre insofern geklärt. Jetzt, was ist mit den letzten beiden? Äh – ich muß mich entsinnen, wie ich darauf gekommen bin … Ja! Ich habe Ihnen ja diese Tonleiter vorgespielt. Und die, das ist klar, setzt sich zusammen aus folgenden Terzen:

[spielt Tonfolge bestehend aus c4 – a3 – fis3 – d3 – h2 – g2 – e2 – c4 – a3 … usf.]

Was sind das für Harmonien? Wir haben den D7-Akkord:

[spielt d3 – fis3 – a3 – c4]

Der löst sich in die Tonika auf:

[spielt g2 – h2 – d3]

Und dann die Tonikaparallele:

[spielt e2 – g2 – h2]

D. h., wie wär’s eigentlich, wenn wir an dieser Stelle einmal annehmen, daß wir den D7-Akkord in Takt 29 auflösen zur Tonika, was eindeutig ist, soweit stimmen auch die Bindebögen ganz gut und jetzt erscheint irgendwann die Tonikaparallele, – das kann man sich denken:

[spielt Takt 30 mit dem Akkord der Tonikaparallele auf der vierten 16tel-Note g3]

… und hier schon die Dominante, die oft der Tonikaparallele folgt:

[spielt 2. Hälfte von Takt 30 mit dem Akkord der Dominante auf der vierten 16tel-Note fis3]

… und dann bleibt die Dominante in Takt 31 erhalten. Mit anderen Worten, der vorletzte Bindebogen dieser Passage im Takt 30 beginnt tatsächlich auf der vierten 16tel-Note, also auf dem g3, das ist die Terz der Tonikaparallele: [spielt nochmals Takt 30 beginnend mit dem Bindebogen auf der Note g3, unterlegt mit dem Akkord der Tonikaparallele] … und dann die Dominante:

[spielt 2. Hälfte von Takt 30 beginnend mit dem Bindebogen auf der Note fis3, unterlegt mit dem Akkord der Dominante]

Nun ist das aber sehr ungewöhnlich, weil, … ein Bindebogen mit einer Betonung auf der vierten 16tel-Note einer Zz, das ist also wirklich die unbetonteste Note einer Zz. Und man sträubt sich zunächst einmal, das zu akzeptieren. Aber wenn man versteht, daß mit dieser Tonleiter, mit diesen Bindebögen, uns die Tonikaparallele von JSB nochmals „kredenzt” wird, so ganz unbemerkt, wo sie ja eine so große Rolle im 1. Teil spielte, … so über Skalen, nicht über Harmonien, … sondern es wird mittels Skalen, also melodisch zur Tonikaparallele hingeleitet, dann akzeptiert man auch, daß man hier „aus dem Takt gerät”. Daß es hier eine Stelle ist, die sowohl metrisch wie harmonisch ins Leere mündet, sich auflöst in den „luftleeren Raum”. Und so ist es auch hier.

Anmerkung: Ungewöhnlich bleibt noch die Betonung der Baßnote c3 in Takt 30. Sie wirkt als ein Vorhalt (Dienerton) zur Baßnote h2 der 3. Zz (und weniger als Septim der Dominante, die ein Herrenton wäre). Betrachtet man nochmals den Bindebogen in der Abschrift AMB’s, so fällt ins Auge, daß dieser Bindebogen nicht dezidiert auf der letzten Note d3 in Takt 29 aufhört sondern über diese Note hinaus gezogen und auf die 1. Note c3 des Folgetakts gerichtet ist. Es liegt deshalb nahe, anzunehmen, daß die Anfangsnote c3 des Takt 30 angebunden ist.

In diesem Fall wäre die Spitzentonhöhe h3, die Quint der Tonikaparallele, als Auflösung betont. Ebenso kann man die Spitzentonhöhe a3 der 3. Zz schon der Dominante zurechnen. Folglich sind dann beide Spitzentonhöhen auf der zweiten 16tel-Note der 1. und 3. Zz betont sowie, wie gesagt, auch deren vierte 16tel-Note.

Mit der Anbindung der Baßnote c3 wird übrigens definitiv das Anklingen von a-moll, der Subdominantparallele, ausgegrenzt [s. o.].

Diese Deutung des Bindebogens über sieben 16tel-Noten löst auch ein bogentechnisches Problem, denn auf diese Weise kann der nachfolgende Bindebogen zum Ausgleich im Gegenstrich ausgeführt werden.

Michael Bach