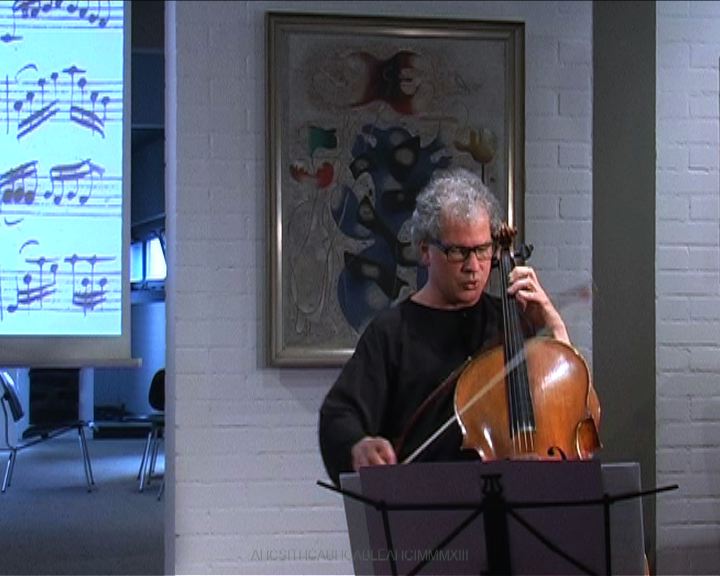

Michael Bach

Dies ist der erste Teil der Transkription meiner Präsentation

„Urtext = Klartext?”

vom 4. Mai 2013 in der Stiftung Domnick in Nürtingen bei Stuttgart

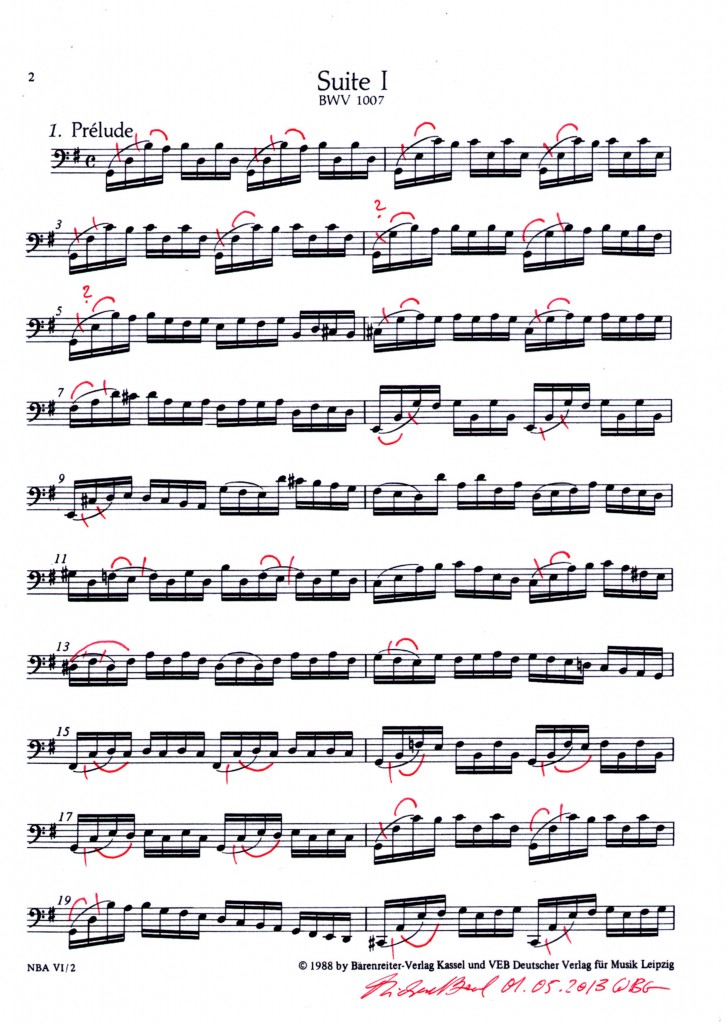

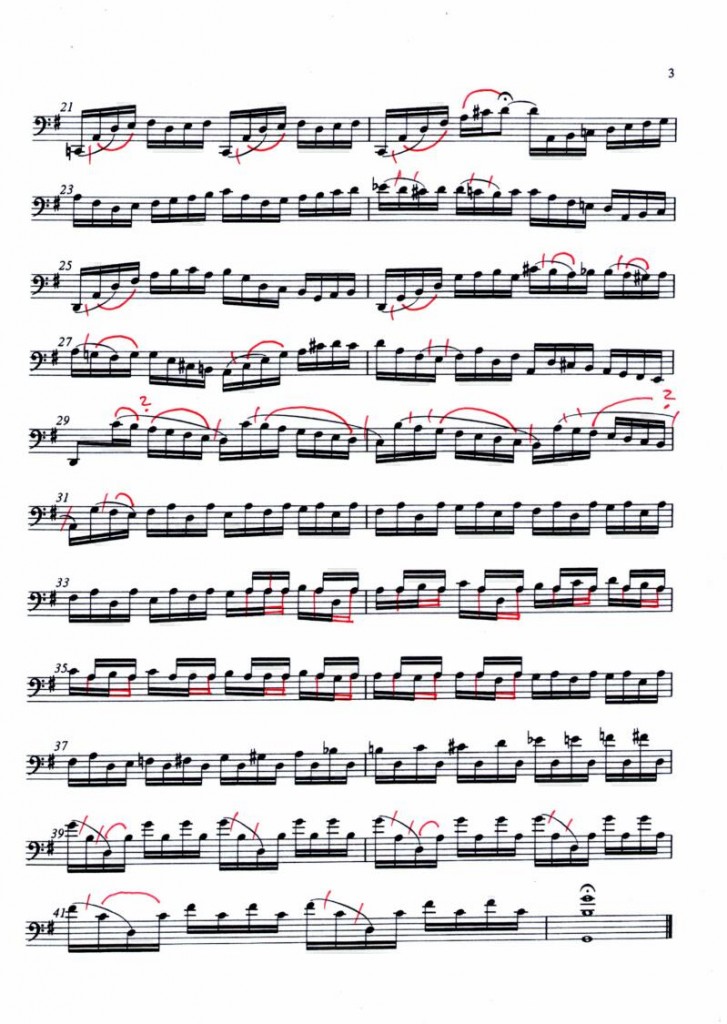

Also, die ersten 5 Takte des Prélude in G-dur:

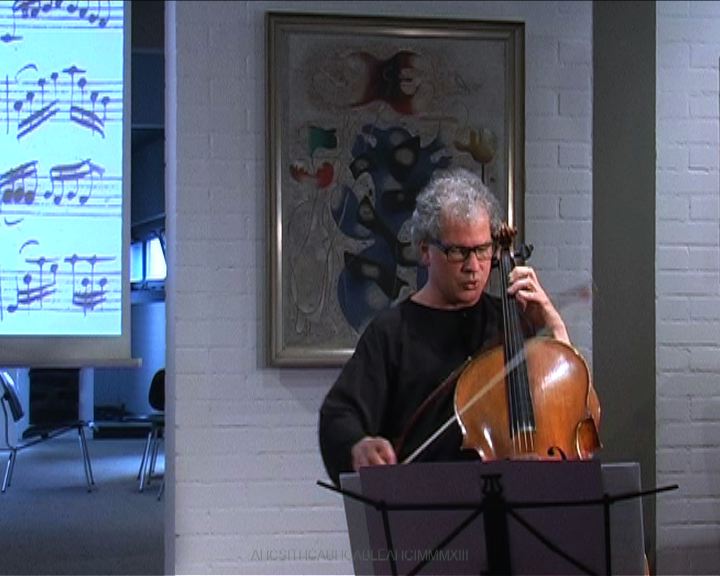

[spielt Takt 1-5 am Cello]

Bach hätte jetzt beispielsweise auch folgendes schreiben können:

[spielt die ersten Takte, aber transponiert nach g-moll]

Warum habe ich Ihnen das jetzt vorgeführt?

Um im Folgenden besser klarmachen zu können, was es heißt, eine Harmoniefolge in der Einstimmigkeit darzustellen.

Ein Harmonieinstrument würde diese Harmonien folgendermaßen spielen:

[spielt die Harmonien als dreistimmige Akkorde mit dem Rundbogen]

Sie sehen, das ist eindeutig: Weil alle 3 Töne eines Dreiklangs zusammen erklingen – und gleichzeitig. Also, das ist an harmonischer Eindeutigkeit nicht mehr zu überbieten.

Wenn aber nun diese Harmoniefolge einstimmig geschehen soll, dann müssen Sie zuerst mal sich fragen, welcher Ton kommt zuerst und welcher folgt, und so weiter.

Neben dem Grundton…

[spielt die Note g2]

…ist die Terz der wichtigste Bestandteil des Akkords. Weil die Terz bestimmt, ob wir Dur oder Moll hören.

[spielt die Noten des Dreiklangs von G-dur und dann von g-moll]

Hier (im Prélude) ist die Terz in der Oberstimme:

[spielt nochmals g-Moll und G-dur, diesmal mit den Terzen b3 und h3 in der Oberstimme]

Also erst, wenn wir diese Terz (h3) hören, dann wissen wir, daß wir in G-dur sind.

So zeigt sich also, daß erst bei dem 3. Ton…

[spielt die ersten Töne des Prélude]

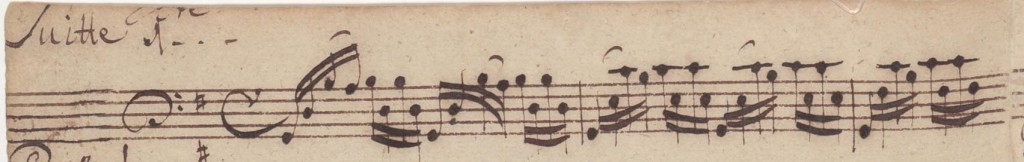

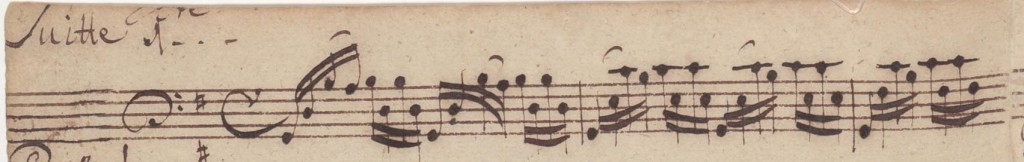

…die Harmonie klar ist, und Bach – oder die Abschrift von Anna Magdalena Bach (AMB) – setzt da den 1. Bindebogen, auf die Note h3.

Im nächsten Takt geschieht folgendes:

[spielt den Beginn des Takt 2]

Mit der Note e4 wissen wir, daß die Harmonie sich ändern wird, wir hören eigentlich schon die Subdominante voraus – d. h. Bach setzt den Bindebogen nicht auf die 3. Note sondern auf die 2. Note im Takt.

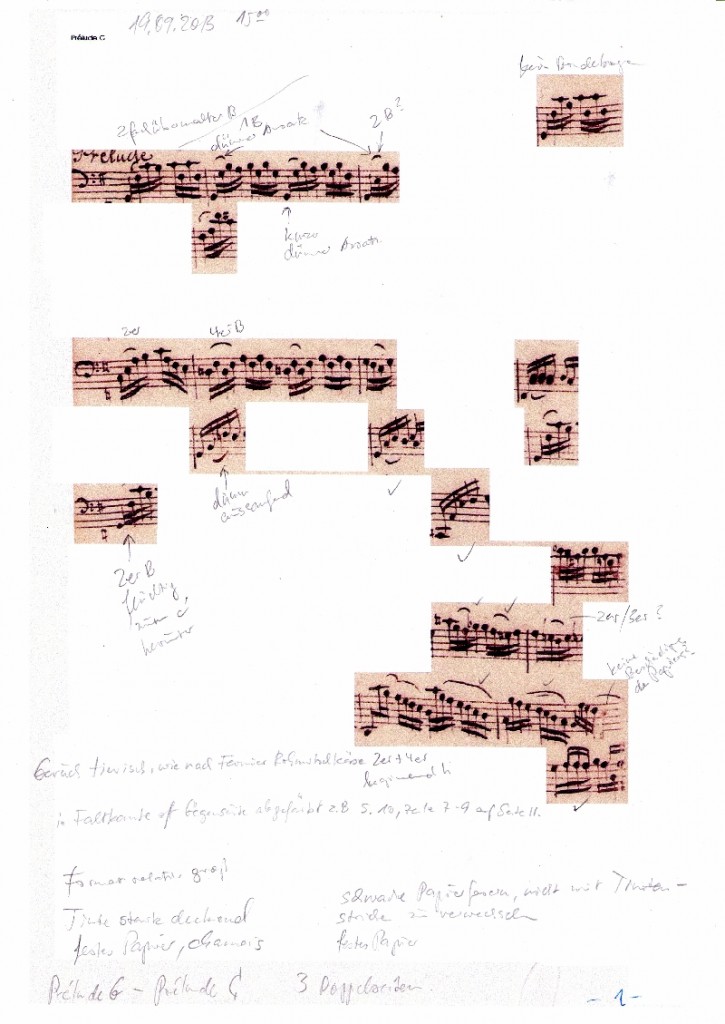

Sie können das hier oben sehen…

[dreht sich nach hinten um, um auf der projizierten Partiturseite die entsprechende Stellen zu zeigen]

…im 1. Takt ist der Bindebogen auf der 3. Note und im 2. Takt auf der 2. Note. Warum?

Weil sich da die Harmonie ändert.

Im 3. Takt ist kein Bindebogen – zunächst…

[spielt die 1. Hälfte des Takt 3]

…erst bei der Wiederholung…

[spielt die 2. Hälfte des Takt 3]

…kommt ein Bindebogen auf der 2. Note. Ich werde darauf nochmal Bezug nehmen.

Um das Ganze etwas plausibler darzustellen, mache ich jetzt eine Anleihe bei Thomas Mann. In seinem Roman „Doktor Faustus” tritt eine skurile Figur auf namens Johann Conrad Beißel. Das klingt fatal nach Johann Sebastian Bach.

Gebürtig aus der Pfalz war er in jungen Jahren nach Pennsylvania ausgewandert und hatte sich dort zum Haupt einer Gemeinde geriert, die sich „Wiedertäufer des Siebenten Tages von Ephrata” nannte. Und er speiste die Seelen der Seinen mit didaktischen Gesangstexten, die auf bekannte Kirchenmelodien zu singen waren.

Irgendwann kam es ihm aber in den Sinn, seine eigenen Texte in Musik zu setzen. Und weil er ein Mann der Tat war, so dekretierte er, daß unter allen Tönen Herren und Diener sein sollten. Kurzerhand hat er die Töne des Dreiklangs zu Meistern oder zu Herren ernannt, und alle übrigen Töne zu Dienertönen.

Auf die betonten Silben eines Textes sollten nun Herrentöne gesetzt werden und auf alle anderen unbetonten Silben die Dienertöne.

In diesem Licht gesehen, hat J. S. Bach offensichtlich die Dienertöne an Herrentöne angebunden.

Also, wenn ich jetzt nochmals spiele…

[spielt den Anfang des Préludes bis zur Note h3]

…Herrenton (h3). Die Note a3 ist ein Dienerton, kein akkordeigener Ton.

[spielt den 1. Takt zu Ende bis Takt 2]

Hier…

[spielt die Note e3]

…entsteht die 1. Ausnahme, denn er bindet jetzt 2 Herrentöne. Das…

[spielt die Note c4]

…ist der Grundton des Akkords (Subdominante). Aber, er gewichtet – anders als Herr Beißel – Bach gewichtet zwischen den Herrentönen, es sind also nicht alle gleich, weil hier die Terz (e4) wichtiger ist, die uns die neue Harmonie bekannt gibt.

[spielt nochmals den 2. Takt]

Und hier gibt es 3 Herrentöne, die nun wirklich nicht zu vereinen sind: Wir haben einmal den Grundton von G-dur, der bleibt als Orgelpunkt liegen, es ist eigentlich ein harmoniefremder Ton (in D-dur, der Dominante)…

[spielt die Dominante mit Septim c4]

…und das sind die beiden Töne der Dominante,…

[spielt fis3 und c4]

…die sich dann wieder in die Tonika auflöst.

[spielt die Auflösung]

Also in Takt 3 sind es 3 Töne, die Herrentöne sind, die sich nicht vereinbaren lassen, und die sind nicht gebunden.

Ich komme darauf zurück, warum in der 2. Takthälfte doch eine Bindung zu finden ist.

Nun, ist ja klar, welche Auswirkungen hat ein Bindebogen?

Ich schließe aus diesen ersten Takten des Prélude, daß diejenige Note, auf der der Bindebogen steht, hervorgehoben werden soll.

Wie das geschieht, ist dem Interpreten überlassen. Er kann die Note akzentuieren, sie lauter spielen, sie dehnen, also ein tenuto machen, oder er kann agogische Veränderungen machen, er kann sie etwas früher bringen oder später – das schreibt Bach nicht vor, aber er schreibt einen Bindebogen, welcher anzeigt, daß der 1. Ton eines Bindebogens wichtig ist.

Nun möchte ich noch eine Sache vorwegnehmen: Der Ton nach der Bindung ist auch wichtig. Und er ist um so wichtiger, je länger der Bindebogen ist. D. h., wenn wir einen ganz langen Bindebogen haben, dann ist diejenige Note nach dem langen Bindebogen um so mehr betont. Aber das werde ich gleich noch näher erklären, jetzt zunächst nochmal:

[spielt den 1. Takt bis zur 2. Note h3 der 2. Zählzeit]

Also, diese Note h3 (nach dem Bindebogen) wird auch betont.

[spielt weiter bis Takt 2]

Jetzt fragt man sich, nach den beiden gebundenen „Herrentönen”, nun ein „Dienerton” (h3): Ja, warum ist dieser „Dienerton” jetzt betont?

Der Grund liegt darin, daß wir es eigentlich mit 2 Harmonien zu tun haben. Wir haben zwar eindeutig eine Subdominante…

[spielt Subdominante]

…die auch die Note g enthält, wir haben aber gleichzeitig immer noch die Tonika, die auch die Note g hat.

Und im nächsten Takt werden wir sehen, daß wir es mit einem Orgelpunkt zu tun haben, daß wir tatsächlich mehrere Harmonien im Takt haben. Es ist deshalb gerechtfertigt, die Note h3 (in Takt 2) zu betonen, weil das die Terz dieses Grundtons (Orgelpunkt g2) ist.

Also, das ist kein Widerspruch (die Betonung der Note h3) sondern das macht Sinn.

Jetzt im 3. Takt haben wir das:

[spielt die ersten 3 Töne]

Diese 3 Töne stoßen sich gegenseitig ab, wir haben eine große Septim, die sich zur Note g3 auflösen müßte, und ein c4, das sich nach h3 auflösen müßte:

[spielt zweistimmig die Noten fis3/c4 und dann g3/h3]

Den Tritonus fis3/c4 kann man nicht binden,

Anmerkung:

Der Tritonus ist in den Suiten fast nie gebunden, da er aus 2 akkordeigenen Herrentönen besteht. In diesem Prélude tritt aber zuweilen eine Bindung der Noten fis3 und c4 respektive h2 und f3 auf. Diese Ausnahmen werden an den jeweiligen Stellen erklärt.

aber in der 2. Takthälfte werden diese Noten gebunden…

[spielt die 2. Takthälfte]

…weil Bach die Auflösung vorwegnimmt, die Note h4 wird nämlich betont, das ist die Auflösung (Terz der Tonika).

Dieser Takt wird später nochmals eine Rolle spielen, weil auf diese Artikulation (Bindebögen) wird nochmals Bezug genommen.

Es ist auch so, das werden wir auch noch sehen: Wenn zunächst im Takt kein Bindebogen da ist und dann ein Bindebogen folgt, wie hier im 3. Takt, dann bedeutet das immer eine emphatische Steigerung bei Bach – eine emphatische Steigerung des Ausdrucks.

Also, ich habe schon erwähnt, daß die Note nach dem Bindebogen auch betont wird.

Das hat physikalische Gründe. Weil die Lautstärke am Cello oder an der Geige hängt von der Strichgeschwindigkeit ab. Ein einfaches Beispiel: Bei einer Tonleiter, wenn ich 7 Töne auf einen Bogenstrich spiele und 1 Ton auf einen Bogenstrich bei gleicher Haarlänge spiele, dann ist der Einzelton zwangsläufig betont:

[spielt G-dur durch 2 Oktaven, steigend und fallend, jeweils 7 Noten im Abstrich und 1 Note im Aufstrich]

Diesen Effekt lernen natürlich Streicher zu kaschieren. Aber J. S. Bach nutzt diese spieltechnische Gegebenheit – seine Artikulation ist wirklich sehr ausgeklügelt,. Z. B. zeigt sich das in einem Takt der Allemande, dem Folgesatz hier. Da haben wir 13 Noten auf einen Bogenstrich, das ist also sehr extrem:

[spielt Takt 13 der Allemande in G-dur]

Das hat Gründe, weil wir haben zuerst die Tonikaparallele…

[spielt die 4 16tel-Noten der ersten Zählzeit]

…jetzt wird aber die Doppeldominante klar…

[spielt die Note cis3 und weiter bis zur Note a3]

…und das ist der Grundton der Doppeldominante (a3) und das die Septim…

[spielt g4]

…und löst sich auf nach D-dur.

Bach nutzt also diese physikalische Gegebenheiten der Bogentechnik ganz extrem.

Nun, die Urtextausgaben machen übereinstimmend aus den ersten Takten des Préludes nun folgendes:

[spielt die ersten Takte in den Fassungen der Urtextausgaben]

Immer einen Bindebogen über drei Noten zu Beginn der 1. und 2. Takthälfte, was eine monotone Baßlastigkeit bewirkt. Ja, es wird sogar abgelenkt, es wird Nebensächliches hervorgehoben, wie immer dieser Baßton g2 – und die Wechselnote, die nach dem Bindebogen kommt.

[demonstriert nochmals am Cello]

Das ist in etwa so, wie wenn man beim Elfmeterschießen ständig auf das falsche Tor zielen würde. (Publikum lacht)

Ich unterbreche die Transkription meines Vortrags, um zusammenfassend zur Anfangskadenz mit Orgelpunkt g2 folgendes anzumerken:

Diese Grundform einer Kadenz, Tonika, Subdominante, Dominante mit Septim und Tonika, auf dem Grundton der Tonika als Orgelpunkt legt, mittels der Bindebögen ihren konstruktiven Aufbau frei.

Der 1. Takt ist harmonisch eindeutig, betont wird mittels der 2-B viermal die Terz h3 der Tonika.

Anmerkung:

Wenn ich vereinfachend von einem Zweier-Bindebogen (2-B) auf der Note h3 spreche, so ist damit gemeint, daß ein Bindebogen über 2 Noten mit der Note h3 beginnt.

Der 2. Takt ist harmonisch zweideutig. Er beherbergt die Tonika und die Subdominante. Betont wird mittels der 2-B die Terz e3 der Subdominante und die Terz h3 der Tonika.

Der 3. Takt enthält drei Harmonien: die Tonika (Grundton g2), die Subdominante (Grundton c4) und die Dominante (Terz fis3). Es findet sich deshalb in der 1. Takthälfte kein Bindebogen, da ein Bindebogen eine hierarchische Ordnung unter diesen Tonhöhen schaffen würde. Die 3 Tonhöhen stehen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Erst in der 2. Takthälfte führt der 2-B zu einer Betonung der Terz fis3 der Dominante und infolge der Anbindung der Note c4 zu einer Betonung der Terz h3 der Tonika. Die Auflösung der Dominante zur Tonika klingt hier somit schon an.

Die Hervorhebung der Note h3, in diesen 3 Anfangstakten hat noch eine weitreichendere Bedeutung, die im weiteren Verlauf des Prélude immer deutlicher wird: Die Tonikaparallele (e-moll) ist neben der Tonika in diesem Satz die zweitwichtigste Harmonie. Diese beiden Harmonien bilden so etwas wie 2 harmonische Gravitationsfelder. Der 2. Takt könnte sogar als Tonikaparallele mit Sextvorhalt c4 gehört werden. D. h. die Note c4 wäre in dieser harmonischen Deutung ein Dienerton (Vorhalt), der an den Grundton e3 angebunden ist und die Note h3 wäre tatsächlich ein betonter Herrenton.

Doch zu diesem harmonischen Doppelbezug im Teil 2 der Transkription bald mehr…

Analyse Teil 2