On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the death of Tossy Spivakovsky

(December 23, 1906 – July 20, 1998), who became one of the first violinists to interpret the “Sonatas and Partitas” for violin solo by J. S. Bach with the curved bow, I present this transcript of his introductory speech, which was released recently together with the live recording of the “Chaconne” on the label DOREMI.

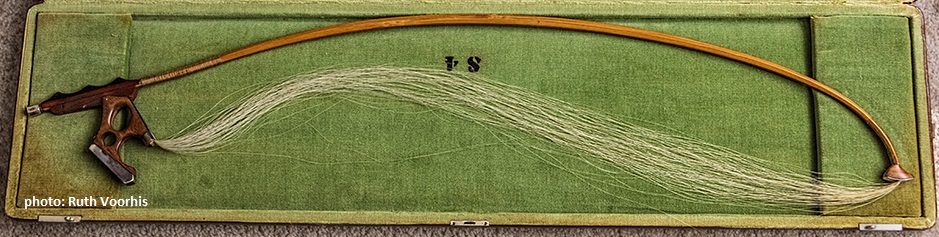

VEGA BACH Bow of Tossy Spivakovsky

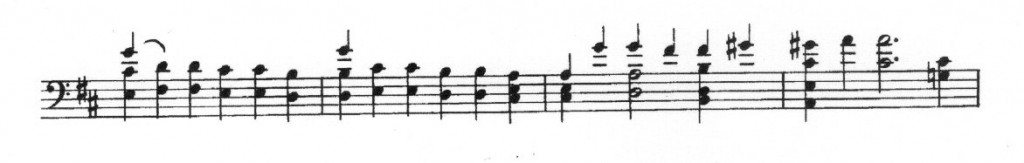

“The six works for unaccompanied violin by Bach demand of the executant a mastery of seemingly insoluble technical problems such as multiple stops and polyphonic voice progressions. It is sometimes thought, erroneously, that Bach intended all such chords to be arpeggiated. But one can clearly see from Bach’s own handwriting of these works that the composer distinguished broken from unbroken chords quite explicitly. When he wanted them arpeggiated he wrote the sign “arp.” with the respective chords. All chords, as in [those without] such special indications, were of course meant to be played unbrokenly, all notes sounded simultaneously. Therefore the well known sound of notoriously breaking or rolling all chords causes distortions of what is written and is not only unpleasant to listen to but also from a musicological point of view incorrect.

By means of the recently manufactured curved bow patterned approximately after the Renaissance or early Baroque bow the violinist is nowadays able to play even quadruple chords unbrokenly. It might be said that it is anachronistic and therefore incongruous to use a curved bow on a modernized violin with its lengthened neck and bass bar. But this objection is not valid. The violin with these lengths and proportions sounds only fuller, stronger and more resonant. The tone quality remains the same. I think, very little would be accomplished when playing 18th century music to use the old adjustment on violins.

There is of course no tradition of performing Bach’s Solo Sonatas. The manuscripts of these six works remained unpublished throughout Bach’s life. They were performed for the first time more than a hundred years after his death. Thus, the public only gradually learned to know about these works and this happened at the time when the romantic spirit was at its height, a period rather far removed from the essence of Bach’s polyphony.

Therefore the way the violinist played these works at that time, the second half of the 19th century cannot serve as a model for performance of Bach. Indeed according to the latest research it went quite contrary to the composer’s intention.

So, I am using such a curved bow, now.”

Live Broadcast, Swedish Radio, Stockholm, January 26, 1969

DOREMI, Legendary Treasures, DHR – 8025

Category Archives: Allgemein

Tossi Spiwakowski, Einführung zur Interpretation von J. S. Bachs Solowerken für Violine mit dem Rundbogen

Anläßlich des 20. Todestages von Tossi Spiwakowski ( 23. Dezember 1906 – 20. Juli 1998), welcher sich als einer der ersten Violinisten für die Interpretation der “Sonaten und Partiten” für Violine solo von J. S. Bach mit dem Rundbogen einsetzte, erscheint diese Übersetzung seiner Einführungsrede, die zusammen mit dem Live-Mitschnitt der “Chaconne” kürzlich unter dem Label DOREMI veröffentlicht wurde.

VEGA BACH Bow von Tossi Spiwakowski

“Die sechs Werke für Violine solo von Bach verlangen von dem Ausführenden die Beherrschung von anscheinend unlösbaren technischen Problemen wie das Spielen von Mehrklängen und polyphoner Stimmführung. Es wird manchmal irrtümlich angenommen, daß Bach diese Akkorde arpeggiert haben wollte. Aber man kann klar aus Bachs eigener Handschrift dieser Werke erkennen, daß der Komponist deutlich zwischen gebrochenen und nicht gebrochenen Akkorden unterschied. Wenn er sie arpeggiert haben wollte, schrieb er das Zeichen “arp.” bei den entsprechenden Akkorden. Alle anderen Akkorde, ohne diese spezielle Angabe, sollten selbstverständlich ungebrochen gespielt werden, alle Akkordnoten erklangen gleichzeitig. Daher führt der uns wohlbekannte Klang, alle Akkorde notorisch zu brechen oder zu arpeggieren, zu Verzerrungen des geschriebenen Notentexts, was nicht nur klanglich unzufriedenstellend sondern auch unter dem musikwissenschaftlichen Gesichtspunkt inkorrekt ist.

Mithilfe des kürzlich hergestellten Rundbogens, der annähernd dem Renaissance- oder Barockbogen nachgestaltet ist, kann der Geiger heutzutage sogar vierstimmige Akkorde ungebrochen spielen. Man könnte sagen, daß es anachronistisch und deshalb unpassend sei, einen Rundbogen auf einer modernisierten Geige mit ihrem verlängerten Hals und Bassbalken zu benutzen. Doch dieser Einwand zählt nicht. Die Violine mit diesen Längen und Proportionen klingt lediglich voller, stärker und resonanter. Die Tonqualität bleibt dieselbe. Ich glaube, daß sehr wenig erreicht sein würde, wenn man für die Musik des 18. Jahrhunderts die alte Einrichtung der Violinen verwenden würde.

Es gibt freilich für die Solosonaten von Bach keine Aufführungstradition. Das Manuskript dieser sechs Werke blieb zu Bachs Lebzeiten unveröffentlicht. Sie wurden erst mehr als hundert Jahre nach dessen Tod aufgeführt. Infolgedessen lernte die Öffentlichkeit nur allmählig diese Werke kennen und das geschah zu einer Zeit, als der romantische Geist seinen Höhepunkt erreichte, in einer Periode also, die ziemlich weit vom Wesen der Bachschen Polyphonie entfernt war. Deshalb kann die Art und Weise, wie die Geiger in dieser Zeit diese Werke spielten, in der 2. Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, nicht als Leitbild für die Aufführung von Bach dienen. Tatsächlich steht sie, laut den aktuellen Erkenntnissen, den Absichten des Komponisten ziemlich konträr entgegen.

Deshalb verwende ich jetzt einen solchen Rundbogen.”

Live-Sendung des Schwedischen Rundfunks, Stockholm, 26. Januar 1969

DOREMI, Legendary Treasures, DHR – 8025

Urtext = Plain Text ? – An Analysis of the Sarabande in D Major, Part 1 (Bar 1-8)

This is a translation of the post

Urtext = Klartext? – eine Analyse der Sarabande in D-Dur, Teil 1 (Takt 1-8)

by Dr. Marshall Tuttle

Michael Bach

This is the first part of the analysis of the

“Sarabande” in D Major

Guest:

Burkard Weber

Video:

Interpretation of “Sarabande in D Major”

Michael Bach, Violoncello with BACH.Bogen:

https://youtu.be/YuqXQgfPKkg

Lecture on YouTube:

Bach, Sarabande D-Dur Cello solo | Analyse Michael Bach | Teil 1

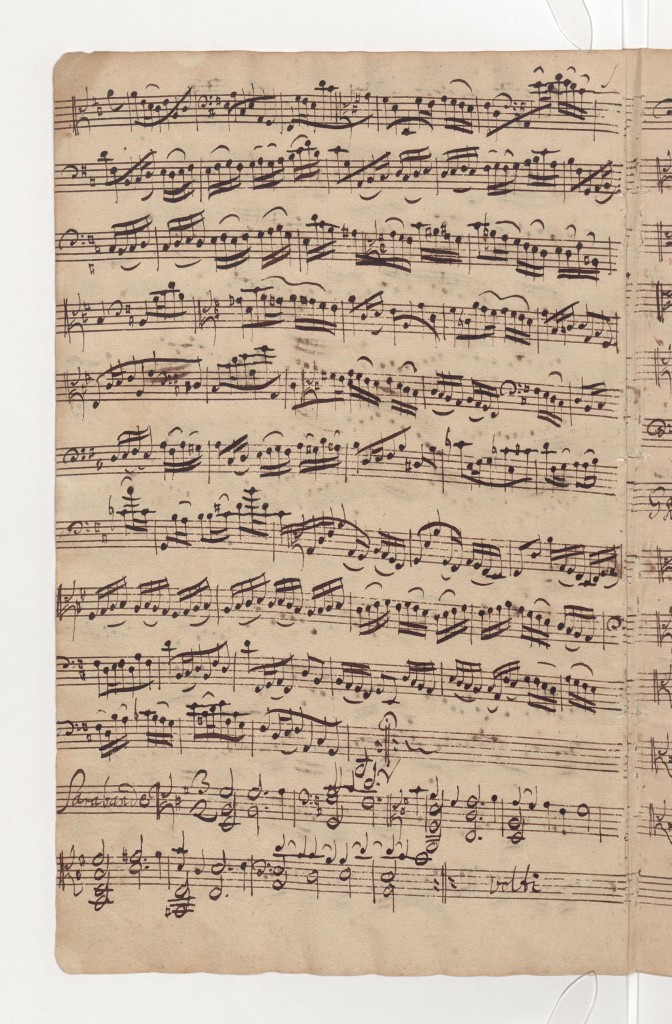

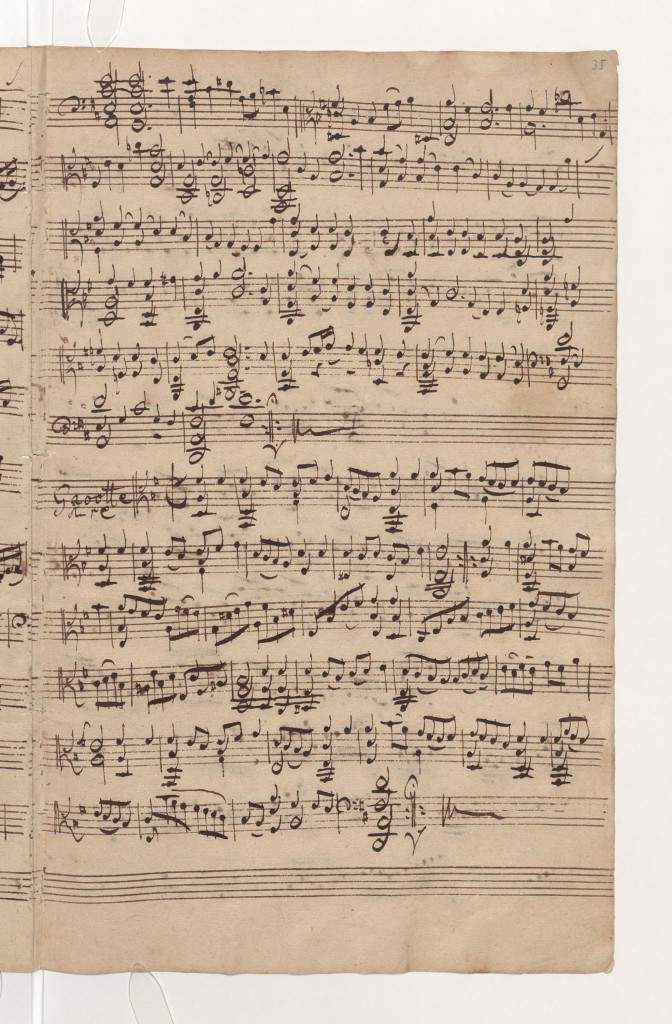

Copy of Anna Magdalena Bach, digital copy from the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin – PK

MB (Michael Bach): Here, in this piece, it there is a harmonic meaning, which is why we have monophony and two-, three-, and four-part passages.

There are many musicians, or almost all, who claim that the note values are not to be taken precisely. In my opinion, it is quite clear that they must be rendered exactly.

Because, in this movement, for example, the bass is usually not resolved. This can only be heard when the bass is held to the end.

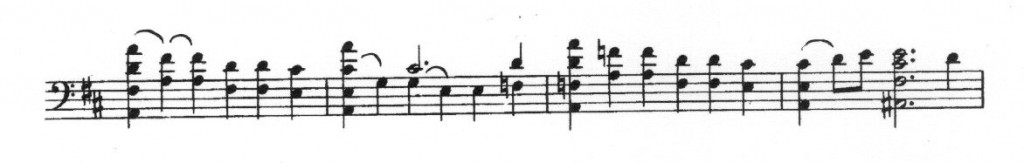

Measure 1

Let us take the first measure. We have D major. [plays bar 1]

What is the second sound? We have a reduced D major sound.

If this were focused on this second sound, Bach would have composed like this: [plays first the two-part and then the three-part harmony]

One would think this version is almost the same.

If you look at the first 8 bars, the second beat is always reduced in the number of notes. Often, a four-voice chord occurs on the 1st beat, and then a two note chord, or sometimes a three note chord, or sometimes even a single note, appears on the second beat

So, I can not imagine it being played like this: [emphasizes the double stop on the second beat instead of the three part chord on the first beat.

It is rather the opposite, that the second beat is “incomplete” and I play it slightly dynamically reduced, because we do not know …

This is always the case with Bach. When he changes from three- or four-parts to two-parts it means something. In this case, it is an opening to other harmonies.

Because, I could imagine this harmony now: [plays in B minor]

Only, the listener does not imagine this, because he has to be moved first of all. He does not imagine a C# in the bass (tonic chord of the mediant, F sharp minor). But it would be possible that the G does not appear at the end of the measure, but a G#. Then we would be in the mediant, or relative minor of the dominant.

But the G appears, and it is interesting again that this is a single note.

If Bach had left this previous A, then a minor seventh would arise. This happens later in measure 13: [plays measure 13]

We’ll talk about that later. In any case, when I hear this seventh, I am already thinking of a dominant, namely: [plays A – C# – E – G]

Measure 2

This does not happen, however. The piece continues with the G of the subdominant in the first beat of the second bar.

And here the focus is effectively on the second beat. That is, the resolution to D major. Although we only have a two-part chord, it is clear, this is D major.

The first chord of the second bar is interesting: First, it is not playable. The 6th Suite is written for a five-string instrument. We have the difficulty that we do not have the E-string and therefore there are a few modifications.

But here, with this chord: [plays G – G – B – E], that would still be playable on a five-string instrument, but not that: [plays G – G – B – C#] because C# is below the E-string.

That is, one must omit a tone here if one does not want to break the chord. By the way, I’ve never heard a cellist playing all four notes.

What sound do we want to leave out now? There are 2 possibilities. We have this chord first: [plays G – G – B – E]. Here I also omit the doubled G, which is “painless”.

Furthermore, one could play as follows: [plays G – G – C#], leaving out the B, but now playing the previously omitted octave G. Then we have an ordinary resolution of the Tritone (G – C#) to D major (F# – D).

I am not doing this, but I want to intensify the dissonance and play: [plays G – B – C#] this strong dissonance with C# and B.

BW (Burkard Weber): This is a pungent resolution, but it is nice.

MB: Yes, that’s how it is.

There is now one more thing: the notated note values. There are half notes in the lower voices and quarter notes in the upper voices.

Normally these quarter notes would now be slurred. Because always … [plays a short passage from the Gavotte II in D major, bars 12ff] There are also no slurs, but in the lower voice are quarters and in the upper voice are quavers.

As a rule, therefore, in almost all cases in the case of Bach, the upper voice is then slurred. This also means that the tied second note is unstressed.

This is my observation, which I have made when examining the slurs. I am talking about a Slur Codex. There are about 10 rules with small modifications.

One of the rules is that if there are longer note values in a chord, below or above, and one voice moves, it is slurred.

And then there is one more thing that I discovered when studying the Chaconne for violin solo. This is due to the fact that we do not have such highly chordal movements on the cello where such a thing occurs. That if longer and shorter note values are played together, it is played dynamically as if there were a single all-embracing slur.

I take this measure [plays bar 4] to mean that the first note after the slur is emphasized.

This is all a little quick and complicated and maybe not so easy to understand …

Here, in the Sarabande in D major, there is an exception to the fact that Bach sometimes notates slurs (bars 4 and 7) and sometimes does not in such cases (bars 2, 3 and 6).

This means, for example, if he writes a slur in bar 4 [plays the first beat in bar 4], the resolution (F#) is unstressed and the next note (G) is emphasized. If he had not written this slur, the resolution would not be unstressed, let’s say so. This occurs elsewhere (bar 23).

This means that whenever there is no slur, the second chord is not attenuated, but rather is amplified even more [plays the first beat of measure 2].

It is interesting here, again, that the bass is not resolved. He could go from G to F#. The F# is found in the voice above, but not in the bass [plays the second beat of bar 2].

The fact that Bach does not resolve increases the expectation.

In the following measure, D major appears [plays the first beat of measure 3], but that is not a direct resolution.

We will now see how this will develop. The first bar has already given us the clue, a question mark: why does Bach omit the bass here, in the second beat of the bar?

On the other hand, [plays bars 2 and 3], the second beat is emphasized, which is the paradox in this piece, that often the second beat is emphasized, even though the number of notes is reduced. Continue reading

Urtext = Klartext? – eine Analyse der Sarabande in D-Dur, Teil 4 (Takt 25-32)

Michael Bach

Dies ist der vierte Teil der Analyse der

Sarabande in D-Dur

Gast:

Burkard Weber

Video:

Interpretation der “Sarabande in D-Dur”

Michael Bach, Violoncello mit BACH.Bogen:

https://youtu.be/YuqXQgfPKkg

Analyse:

https://youtu.be/3vUgrV05eZg

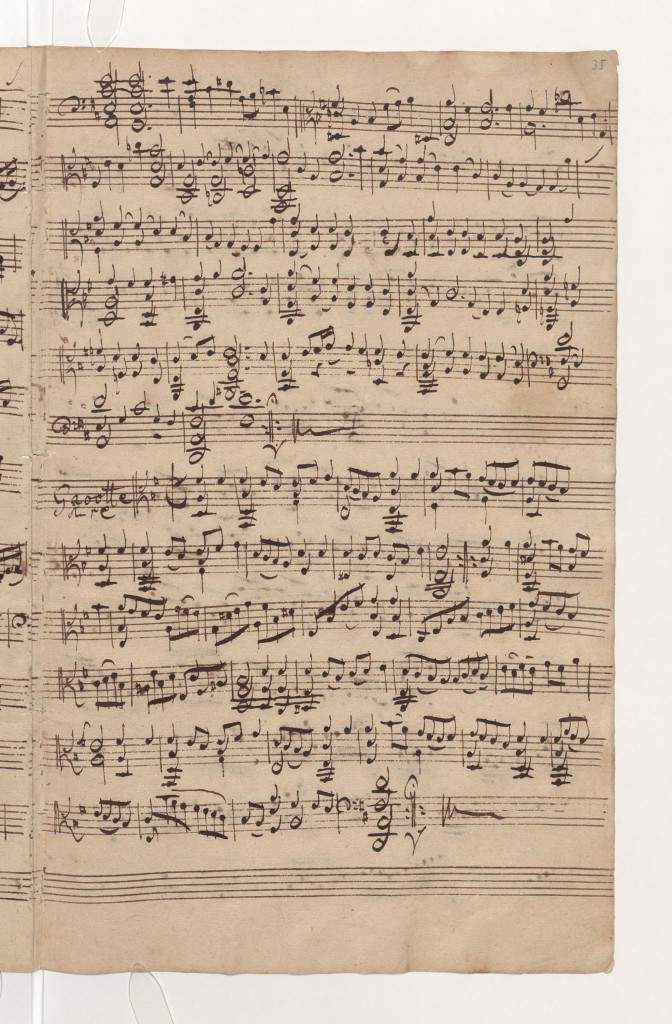

Abschrift von Anna Magdalena Bach, Digitalisat der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK

Teil 4

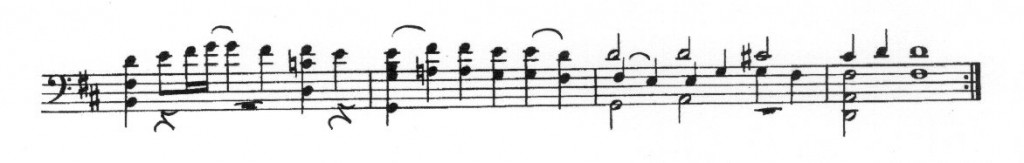

Takt 25

In den folgenden 3 Takten stehen vierstimmige Akkorde auf der 1. Zählzeit. Der erste ist auch betont, der zweite auch … allein schon dadurch, daß sie vierstimmig sind. Das muß man auch beachten, wie soll ich sagen, dadurch daß sich die Regeln des Bindbogen-Kodex durchkreuzen …

Es gibt manchmal den Fall, daß die Bindebögen zwar suggerieren, daß eine Zählzeit unbetont ist, aber da steht auf einmal ein vierstimmiger Akkord. Der ist natürlich akzentuiert.

In Takt 25 hat Bach einen Haltebogen im Anschluß an den Bindebogen geschrieben. D. h. daß die Zwischenzählzeit, zwischen der 2. und 3. Zählzeit, betont wird. Das ist die Tonika.

Also, wir kommen hier sozusagen “aus dem Takt”.

Takt 26

In der 1. Zählzeit schreibt Bach einen Bindebogen. Der Tritonus der 2. Zählzeit ist betont, das e ist angebunden, die Repetition des e kann nicht angebunden werden, trotzdem, infolge der punktierten Halben Note in der Oberstimme, entsteht ein decrescendo:

Takt 27

Zu d-moll, was eine Überraschung ist. Man erwartet ja eigentlich D-Dur, aber es erscheint d-moll.

Takt 28

Die Dominante erklingt. Die Note ais im Baß bedeutet eine Zwischendominante, diejenige von h-moll.

Die Harmonie h-moll, die bislang nicht vorbereitet worden war, wird jetzt durch einen vierstimmigen Akkord mit dem einprägsamen ais im Baß, also mit ihrer eigenen Zwischendominante, tatsächlich etabliert.

Takt 29

Das ist die Tonikaparallele h-moll (1. Zählzeit).

Übrigens, ungewöhnlich ist im Vortakt der Bindebogen zur 1. Achtelnote d – und nicht über beide Achtelnoten – wodurch die Note e akzentuiert wird. Bach möchte, daß die Achtelnote e deutlich ist.

Bach schreibt hier zum 1. Mal Pausen in die Unterstimme. Das ist sehr ungewöhnlich.

Ich habe mich auch gefragt, welche Harmonien haben wir hier eigentlich? Könnte das z. B. die Dominante sein? [spielt die 2. Zählzeit mit cis und a in den Unterstimmen] Wäre möglich.

Oder kommen wir langsam von h-moll wieder nach G-Dur, zur Subdominante? Es könnte sich sogar die Tonika daraus entwickeln.

Ich habe einmal nachgeschaut – wenn es um Tonhöhen geht, schaue ich manchmal bei Kellner nach, das ist die 2. Abschrift, die wir haben. Eigentlich die erste, zeitlich vor derjenigen von Anna Magdalena Bach entstanden.

Da bin ich tatsächlich fündig geworden, denn Kellner schreibt eine kleine Vorschlagsnote vor das e, nämlich ein cis. Damit ist die Dominante klar. Aber, ich glaube, daß das eine Zutat von Kellner ist. So etwas findet man manchmal bei ihm, er war ja Kompositionsschüler von Bach.

Aber Kellner hat sich offensichtlich auch “am Kopf gekratzt”: Was sind hier eigentlich für Harmonien, wo diese Pausen dastehen? Bach hätte doch ein paar Noten mehr hinschreiben können, damit wir wissen, wo wir uns harmonisch befinden. Bach hat das bewußt nicht gemacht.

Und dann noch eine Besonderheit an dieser Stelle: Es gibt einen kleinen Bindebogen und der steht eigentlich als Haltebogen über dem hohen g.

Dies ist so ungewöhnlich, eine Sechzehntelnote synkopisch vor der nächsten Zählzeit anzubinden, daß ich mir lange Zeit Gedanken gemacht habe, ob dieser Bindebogen einfach nur verrutscht ist. Müßte dieser Bindebogen nicht eigentlich auf dem fis stehen? Aber das fis ist die Terz der Tonika und wäre dadurch stärker hervorgehoben, mit einem kleinen Bindebogen …

Jedenfalls, egal wo der Bindebogen steht, die Spitzennote g wäre in beiden Fällen akzentuiert.

Also, wenn ich so spiele [spielt den Bindebogen auf der Note fis], wäre die 2. Zählzeit mit der Spitzennote g akzentuiert, laut Bindebogen-Kodex.

Wenn ich hingegen so spiele [spielt einen Haltebogen auf der Note g], ist die Spitzennote g auch akzentuiert. Ich dehne sogar das g ein wenig.

Mir scheint diese Version ungewöhnlicher zu sein. Deshalb spiele ich diesen Bindebogen so, wie er dasteht. Es gibt keinen Grund, aus meiner Sicht, es anders zu spielen.

Und jetzt, in der 3. Zählzeit ist eindeutig ein Dominantseptakkord, genauer: die Zwischendominante zur Subdominante. Am Taktende ist wieder eine Pause im Baß.

Urtext = Klartext? – eine Analyse der Sarabande in D-Dur, Teil 3 (Takt 17-24)

Michael Bach

Dies ist der dritte Teil der Analyse der

Sarabande in D-Dur

Gast:

Burkard Weber

Video:

Interpretation der “Sarabande in D-Dur”

Michael Bach, Violoncello mit BACH.Bogen:

https://youtu.be/YuqXQgfPKkg

Analyse:

https://youtu.be/3vUgrV05eZg

Abschrift von Anna Magdalena Bach, Digitalisat der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK

Teil 3

Takt 17

Hier haben wir nun eine einstimmige Passage. Jetzt sind wir bei der Subdominante angelangt, gehen mal kurz zur Tonika und zur Dominante und alles hat sich beruhigt.

Es ist auch ganz typisch, wie Bach das macht: [fängt in Takt 17 an zu spielen] also Subdominante, über die Sext e entsteht die Dominante.

Takt 18

Das cis der 1. Zählzeit des Takt 18 ist betont. Und dann ist die 3. Zählzeit betont, das g, das zur Septim der Dominante wird. Der Auftakt a ist unbetont angebunden.

Takt 19

Die Tonika in der 3. Zählzeit (d) ist betont [spielt weiter], das erkläre ich gleich.

Takt 20

Das g der 2. Zählzeit ist betont.

Takt 21

Jetzt erklingt die Dominante.

Takt 22

In der 1. Zählzeit erklingt die Subdominante, aber wir haben immer noch die Tonhöhen der Dominante und der Tonika mit dabei. Wenn Skalen da sind, oder Zweistimmigkeit in dieser Weise, dann ist die Harmonie oft nicht eindeutig.

Man kann insofern mehrere Harmonien mithören, es bleibt offen, wohin das führen wird. Aber hier [spielt weiter] haben wir am Taktende einen vollständigen Dominant-Akkord, …

Takt 23

… gefolgt von der Septim g. Nun die Tonika mit Quartvorhalt g, dann die Auflösung zu fis. Im Gegensatz zu Takt 4, wo die Auflösung angebunden ist, ist sie hier deutlich zu spielen. Warum?

Weil Bach sofort zur Tonikaparallele geht (3. Zählzeit). Das ist nämlich der gleiche Akkord, der in Takt 5 steht. Nur ist dort das “Umspielungsmotiv” zwischen der Tonika und der Tonikaparallele angesiedelt. Hier ist keine Zeit dazwischen.