Michael Bach

Dies ist der erste Teil der Analyse der

Sarabande in Es-Dur

mit Klangbeispielen

und den Interpretationen im Cello-Wettbewerb *)

Interpretation der “Sarabande in Es-Dur”

Michael Bach, Violoncello mit BACH.Bogen

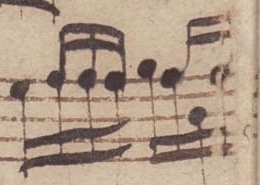

Abschrift von Anna Magdalena Bach, Digitalisat der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK

Glossar:

JSB = Johann Sebastian Bach

AMB = Anna Magdalena Bach

2-B, 3-B, 4-B = Bindebogen über 2, 3 oder 4 Noten

drei 2-Bn = drei Bindebögen über 2 Noten

1. Zz = 1. Zählzeit eines Takts

Zzn = Zählzeiten

T, Te, Tn = Takt, Takte, Takten

c4 = c’

Sub = Subdominante

Dom = Dominante

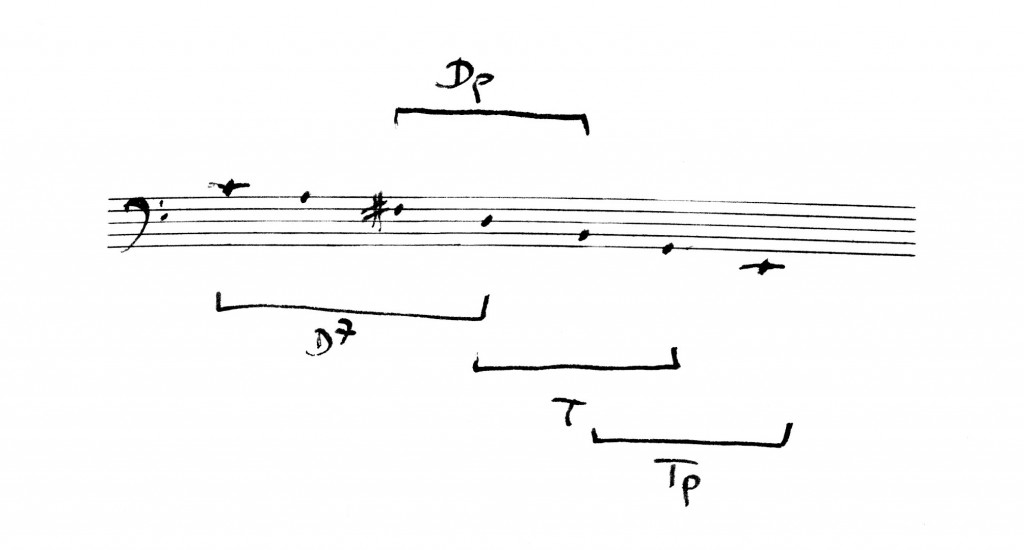

Tp = Tonikaparallele

Sp = Subdominantparallele

Dp = Dominantparallele

DD = Doppeldominante

D7-Akkord= Dominantseptakkord

D9-Akkord = Dominantnonakkord

s6-Akkord = Mollsubdominante mit Sext statt Quint

ZD = Zwischendominante

ZDD = Dominante der Zwischendominante

Vorbemerkung

Die Analyse der „Sarabande in Es-dur” von JSB wird hier den einzelnen Interpretationen der Teilnehmer am diesjährigen Cello-Wettbewerb für Neue Musik in Stuttgart *) gegenübergestellt. Dies geschieht deshalb, um die Frage zu erhellen, inwieweit die heutigen, aktuellen Interpretationen dem überlieferten Notentext gerecht werden. Bei dieser “Sarabande” weichen die Urtextausgaben von der Abschrift AMB’s nicht wesentlich ab und es sind keine Schreibfehler AMB’s zu konstatieren. Es hat sich dennoch eine Aufführungskonvention etabliert, die den Notentext im Grunde genommen abändert. Dies betrifft die Mehrstimmigkeit, als auch die Bindebögen und das Hinzufügen von “Verzierungen”.

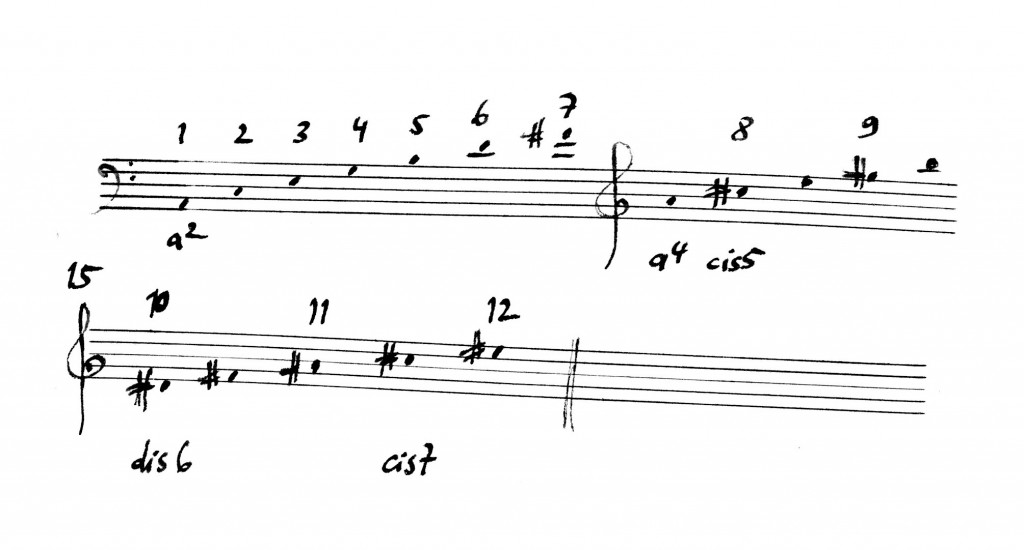

Es scheint nicht allgemeines Wissensgut zu sein (auch die Urtextausgaben berücksichtigen das Folgende nicht), daß bei zwei- oder mehrstimmigen Passagen, die längeren Notenwerte den Bogenstrich quasi diktieren, d. h. daß die Töne der anderen Stimmen, welche kürzere Notenwerte aufweisen, dementsprechend gebunden sind, z. B. hier in den Anfangstakten.

Wichtiger als die Bindungen sind jedoch die Betonungen, die implizit mitnotiert werden. Folglich lassen die Bindebögen eindeutige Rückschlüsse auf agogische und dynamische Prozesse zu, so daß JSB damit ein effektives und gleichzeitig flexibles Notationssymbol zur Hand hatte.

In der Regel sind die Bindebögen identisch mit den Bogenstrichen. Trotzdem kann aus spieltechnischen Gründen einmal ein Bogenstrich verändert werden. Entscheidend bleibt dabei, daß der Sinngehalt eines „kompositorischen” Bindebogens erkannt ist und klanglich entsprechend umgesetzt wird. Dennoch sind die Bindebögen in den „Suiten” fast immer auch identisch mit den optimalen Bogenstrichen. Die beiden Ausnahmen sind in dieser “Sarabande” die Te 29f.

Haltebögen bewirken keine Akzentuierungen, da sie eine Tonhöhe nur verlängern. Allerdings ist in diesem Satz etwas anderes sehr auffällig, nämlich daß JSB dezidiert Haltebögen über den Taktstrich hinweg notiert. Dies führt in den Tn 1 und 3 bei einigen Interpretationen zu dem Mißverständnis, anzunehmen, daß ein Haltebogen sowohl auf den Tonhöhen des4 und as3 fehlt, als auch manchmal an ähnlich aussehenden Stellen, und zwangsläufig ergänzt werden müßte.

Und somit sind wir wieder bei der Harmonik gelandet. Denn alleinig deren eingehende Analyse gibt uns den entscheidenden Clou an die Hand, warum z. B. in den ersten 4 Tn keine Haltebögen vorhanden sind. Der diesen Satz prägende Haltebogen ist demnach weniger als artikulatorische Bindung zu verstehen, sondern vielmehr als ein Zeichen, das den harmonischen Sinnzusammenhang stiftet. Im Cello-Wettbewerb wurde, in Verkennung der Bedeutung des Haltebogens, dieser oft auf alle gleich aussehenden Motive übertragen, ohne die harmonischen Gegebenheiten zu beachten.

Der Haltebogen in dieser „Sarabande” erklärt uns auch, warum z. B. in T 23 nicht der DD7-Akkord sondern der s6-Akkord erklingt. Dies ermöglicht die Überbindung der Note es3 zur 1. Zz des Folgetakts und hat Auswirkungen auf die Gewichtung der einzelnen Akkordtöne untereinander. Das “Fehlen” eines Haltebogens, in den Eingangstakten beispielsweise, gibt uns den Hinweis, daß es sich bei der Septim eines dominantischen Akkords (z. B. as3 in T 3) und dem Quartvorhalt seiner Auflösung (notationsmäßig diesselbe Note as3) streng genommen frequenzmäßig nicht um diesselbe Tonhöhe handelt. Damit werden heutige Thematiken, wie z. B. die der Mikrotonalität, tangiert, die sich jenseits der temperierten Stimmung mit Fragen der Intonation befassen.

Die Tonart Es-Dur wird in den Eingangstakten der „Sarabande” mit ihrer Sub und Dom gefestigt. Die in T 8 zu erwartende DD wird aber, für den Hörer irritierenderweise, in der 1. Satzhälfte „verleugnet”. Die DD tritt dann später in T 21 auf, sozusagen “verspätet” und in Verbindung mit dem Anfangsmotiv, dann aber nur ein einziges Mal und um so überraschender und heroischer.

Hingegen spielen die Moll-Tonarten eine dominierende Rolle, obwohl sie eher im Hintergrund verbleiben. Oft sind sie mit der Dom oder der DD verwechselbar. Sie bewirken so etwas wie ein harmonisches Gravitationsgeflecht, deren Massekörper (Akkorde) nicht explizit in Erscheinung treten.

Eine hervorstechende Besonderheit ist der Triller am Ende der 1. Satzhälfte. An ihm läßt sich exemplarisch zeigen, daß es in den „Suiten” für Cello keine Verzierungen, im herkömmlichen Sinn als „verschönerndes” Ornament verstanden, gibt. Triller sind hier immer ein Indiz für zwei oder mehrere oszillierende Harmonien. Dieser Triller, auf dem Grundton der Dom, nicht auf deren Terz, bewirkt außerdem ein offenes Ende der 1. Satzhälfte, weil dessen Auflösung fehlt. Das etwas ratlose „Trillern” einiger Interpreten im Cello-Wettbewerb findet hierin seine Aufklärung.

Die Rundbogen-Thematik wird in dieser Analyse nicht dargelegt, obwohl die von mir eingespielten Klangbeispiele mit dem Rundbogen ausgeführt sind. Es gibt jedoch 2 Stellen, die ohne den Rundbogen definitiv nicht ausführbar sind: die Te 30f. Für andere Passagen bietet der Rundbogen differenzierte Spielweisen, die der kompositorischen Struktur eher entsprechen, gemäß dem Motto: das beste Instrument ist gerade gut genug für JSB.

Die Mehrstimmigkeit ist, gerade auch was die Notenwerte anbelangt, genauestens notiert. JSB hat nichts Beliebiges oder Austauschbares in diesen Werken niedergeschrieben. Jede Tonhöhe und jeder Notenwert, sowie jeder Bindebogen und jeglicher Triller haben ihre Bewandtnis. Die Abschrift von AMB gibt davon Zeugnis.

*

Der Bindebogen-Kodex

Ich setze hier einige Erkenntnisse, die sich aus meiner detaillierten Analyse aller „Suiten” in der Abschrift von AMB ergeben haben, quasi als Axiome voraus. Ich bezeichne sie als den „Bindebogen-Kodex” in diesen Solowerken für Cello. In der „Sarabande” kommen folgende Regeln in Betracht:

1

Die erste Note unter einem Bindebogen ist betont, sowie die erste nachfolgende Note. Je länger der Bindebogen ist, um so stärker wird die darauffolgende Note betont und um so schwächer ist die erste Note des Bindebogens. Dies führt manchmal zu dem Extremfall, daß außergewöhnlich lange Bindebögen sehr leise beginnen müssen, wobei die Tonhöhen im Anschluß sehr stark akzentuiert sind (z. B. T 13 der “Allemande” in G-dur).

2

Folgen zwei Bindebögen unmittelbar einander, so erhält die erste Note des 2. Bindebogens eine Betonung, wobei die nachfolgenden, angebundenen Noten decrescendieren. Die erste Note nach dem 2. Bindebogen ist infolgedessen unbetont.

3

Bindebögen werden in der Regel nicht notiert, wenn die Mehrstimmigkeit diese sowieso vorgibt.

Die Analyse der „Sarabande in Es-Dur”

… und deren Interpretationen im Cello-Wettbewerb *)

Sarabande in Es-Dur, Edition Michael Bach

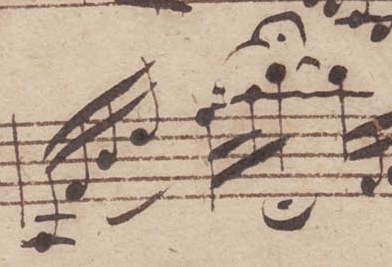

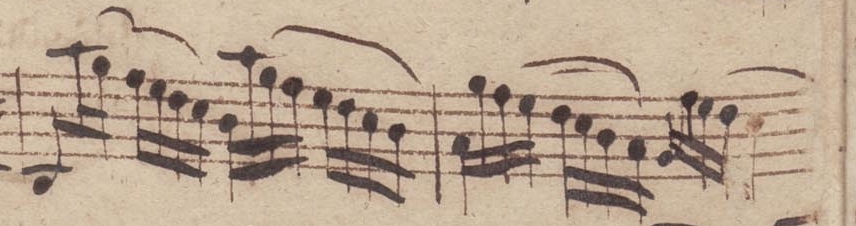

Notenbeispiel T 1-4

Bindebögen, die sich aufgrund der Mehrstimmigkeit von selbst verstehen und die JSB deshalb nicht notieren mußte, sind in Klammern hinzugefügt.

T 1

Der Quintklang zu Beginn spart die Terz aus. (Dieser harmonisch offene Anfang steht im Gegensatz zu T 21, wo das gleiche Motiv in der DD mit Terz erklingt.) Erst mit der 2. Note, dem c4, wird die Durtonart klar, wobei die nachfolgende Septim des4, im Zusammenklang mit der Baßnote es3, das eigentliche Ziel, den dominantischen Charakter dieses Anfangstakts, offenbart. Die Oberstimme ist gebunden, weil in der Unterstimme ein 3/4-Notenwert steht.

T 2

Die 1. Zz wird betont aufgrund des dreistimmigen Akkords und, laut „Bindebogen-Kodex”, weil dem relativ langen Bindebogen des Vortakts naturgemäß eine Betonung folgt. Auch in der 1. Zz des T 2 ist die Oberstimme gebunden, da in den Unterstimmen 1/4-Notenwerte notiert sind. Entsprechend des „Bindebogen-Kodex”, erhält diese 1. Zz nun ein decrescendo. Die Vorhalte lösen sich in der 2. Zz zur Terz c4 der Sub auf, die somit unbetont ist.

T 3

Dieser Takt wird mit einem Auftakt von drei gebundenen 1/16-Noten eingeleitet. Dadurch wird diesmal, im Gegensatz zu T 1, die 1. Zz des T 3 betont. Hieraus folgt, daß der gesamte T3 ein decrescendo erhält.

T 4

Es folgt weiterhin, daß die 1. Zz des T 4 nun unbetont ist, trotz des dreistimmigen Akkords. Die Auflösung der Vorhalte wird nach den beiden Vortakten nun vom Hörer antizipiert. Wegen der Bindung in der 1. Zz wird sodann die Auflösung zur Terz g3 der Tonika in der 2. Zz leicht akzentuiert, sie ist erstmalig eindeutig etabliert.

Anmerkung:

Im T 2 halten sich das kurze decrescendo und das crescendo die Waage, so daß der T 3 an seinem Ende in etwa wieder zur Lautstärke des Satzanfangs zurückkehrt. Hätte JSB eine Wiederholung der Dynamik, d. h. ein crescendo in T 3 gewollt, so wären die drei 1/16-Noten ungebunden. Aber eine Wiederholung der Dynamik der Te 1 und 2 würde der harmonischen Entwicklung widersprechen: Tonika-Sub-Dom-Tonika, die mit der Auflösung zur Tonika in T 4 eine Entspannung bietet. Außerdem würde ein zweimaliges crescendo und leichtes decrescendo in diesen 4 Tn eine Gliederung in 2 mal 2 Takteinheiten kreieren, die die kadenzartige Einleitung spalten würde.

Besonders aufschlußreich sind demnach die Betonungen auf der jeweils 1. Zz der Te 2 und 3 (Sub und Dom), die unbetonten 1. Zzn der Te 1 und 4 und der Akzent auf der Terz g3 der Tonika in T 4, womit die Kadenz ihren Abschluß findet.

Um die Betonung der Dom noch stärker hervorzuheben, wäre ein Akkord in T 3 denkbar, hier aber unlogisch, da das Motiv vom Quintklang ohne Terz geprägt ist. Ein Akkord mit Terz zu Beginn dieses Motives bleibt alleinig der DD in T 21 vorbehalten. Ein Akkord in T 4 hingegen ist auf dem Cello, infolge des Quintfalls im Baß, unausweichlich, denn die mittlere Saite erklingt zwangsläufig, wenn die beiden äußeren Saiten angespielt werden. Die Baßnote es2 ist notwendig, denn durch sie wird der Quartvorhalt in der Oberstimme evident.

Schon in diesen vier Anfangstakten zeigt sich also präzise, wie JSB sich die Gestaltung dieser Eingangskadenz dachte. Er brauchte nur einen einzigen Bindebogen zu notieren, auf den drei 1/16-Noten des T 2. Die anderen Bindebögen, samt Betonungen und Dynamik, ergeben sich wie selbstverständlich aus der komponierten Mehrstimmigkeit.

Die Eingangskadenz ist als harmonische Einheit zu sehen. Es ist das hervorstechendste Merkmal dieses Satzes, daß beharrlich, bis auf wenige markante Stellen, Neuanfänge bzw. Trennungen vermieden werden. Noch nicht einmal werden die beiden Satzhälften klar getrennt, denn der Triller vereitelt eine klare Auflösung zur Dom und bildet keinen deutlichen Schlußton.

Weiterhin: Bei den Tonrepetitionen in der Oberstimme, also der Septim des4 und dem Quartvorhalt des4 respektive der Septim und Quart as3, handelt es sich genau besehen nicht um diesselbe Tonhöhe. Man könnte sogar die Septim etwas tiefer intonieren als die Quart, quasi als Oberton des Grundtons, weil sie mit ihm zusammen erklingt. (In reiner Stimmung wäre das Tonhöhenverhältnis der beiden Noten as3 in den Tn 3 und 4 folgendermaßen: die Quartdezim (Septim plus Quint) 3/2 x 7/4 = 21/8 = 63/24 und die Undezim (Oktav plus Quart) 8/3 = 64/24. Bei einer Frequenz von 78 Hz für den Grundton es2 wäre die Septim der Dom 204,75 Hz und die Quart der Oktav 208 Hz. Das bedeutet eine Differenz von ca. einem Viertelton, denn in diesem Oktavbereich beträgt der Halbtonschritt ca. 12 Hz.)

*

Wie wurde dieser Satzanfang nun im Cello-Wettbewerb gespielt?

Interpretation T 1-4 der 11 Teilnehmer

Die Wettbewerbsbeiträge haben selten die Zweistimmigkeit in den Tn 1 und 3 und das legato in der Oberstimme in den Tn 1 und 3 realisiert. Nie wurde in der 1. Zz der Te 2 und 4 die Oberstimme gebunden.

Manchmal wurde irrtümlicherweise die Septim der 3. Zz an den Quartvorhalt im Folgetakt quasi „gebunden”, indem in der 1. Zz die Tonrepetition in der Oberstimme schlicht weggelassen wurde. Damit soll das synkopische Muster anderer Stellen in etwa kopiert werden (s. Vorbemerkung), denn mit dem konkaven Bogen läßt sich eine fiktive Überbindung nur derart immitieren, da für die Ausführung der beiden Baßnoten die Oberstimme definitiv verlassen werden muß.

Alle im Cello-Wettbewerb vorgeführten Varianten zwingen außerdem zu einer Verkürzung der Baßnoten, die ja ansonsten, infolge eines Bogenwechsels, repetiert werden würden. Die Verkürzung der Baßnoten in den Darbietungen wird aber weder durch eine Analyse des Notentextes noch durch irgendwelche Aufführungstraditionen gerechtfertigt. (Es wird zudem nicht berücksichtigt, daß In JSB’s Notation die Te 13 und 21 ja kürzere Baßnoten enthalten, im Unterschied zu den Tn 1 und 3. Es handelt sich um eine Differenzierung, deren harmonischer Sinn an den entsprechenden Stellen erklärt wird.)

*

T 5

Die nächste Passage bis einschließlich T 7 zeigt nun, warum zweimal eine Überbindung (Haltebogen) über den Taktstrich hinweg erfolgt, jedoch ein einziges Mal nicht (T 6).

Die Note es3 in T 4 wird an die 1. Zz des Folgetakt angebunden, weil die Tonika weiterhin erhalten bleibt. Ein Harmoniewechsel oder eine Auflösung geschieht hier diesmal nicht. In der Unterstimme erscheint die 1/8-Note b2, die Quint der Tonika. Sie kann gehörsmäßig noch nicht als Grundton der Dom erfaßt werden, weil die Terz fehlt, und zumal JSB das b2 auf eine 1/8-Note verkürzt.

Dadurch wird die Note c3 in der Oberstimme der 1. Zz nicht angebunden und somit wird auch nicht die Note d3 der 2. Zz akzentuiert. Die dominantische Funktion bleibt vorerst noch in der Schwebe. Erst mit der Note as3 der 3. Zz, ähnlich wie in den Tn 1 und 3, hat sich die Dom gehörsmäßig etabliert.

Es ist vielleicht an dieser frühen Stelle in der „Sarabande” noch etwas spekulativ, aber ein leiser Anklang der Dp könnte mit den Noten b2 und d3 bereits beabsichtigt sein. Die Dp tritt im gesamten Satz nie prononciert auf, sie ist aber an vielen Stellen latent gegenwärtig.

Statt der Dp hier die Tp zu vermuten, wäre sogar noch etwas wahrscheinlicher, weil die 1/16-Note c3 nicht angebunden ist und, zusammen mit der Note es3, als eine akkordeigende Tonhöhe der Tp aufgefaßt werden kann.

Aus diesen Erwägungen heraus kann mit jeder neu eintretenden Tonhöhe des T 5 eine andere Harmonie erwartet werden: mit c3 die Tp, mit d3 die Dp, mit f3 die Dom. Erst der Tritonus d3-as3 klärt die harmonische Situation schlußendlich zur Dom. Mit der synkopischen Überbindung der Note es3 entsteht also ein „harmonisches Vakuum”, das direkt nach der Eingangskadenz eintritt. Dies wirkt ratlos, fragend und ist ein starkes dramaturgisches Mittel, das in wesentlich effektvollerer Gestalt in T 24 nochmals angewandt wird.

T 6

Der T 6 beginnt mit zwei Harmonien, der Tonika (es2-b2) und der Dom (b2-as3). An der Artikulation und den Notenwerten des Akkords ist dies ablesbar. Denn die 3. Zz des Vortakts, hier die Septim as3, wird diesmal nicht, wie in den Tn 4 auf 5, übergebunden. Auch folgt die Artikulation nicht dem motivischen Muster der Te 2 und 4 und führt nicht zur vertrauten harmonischen Abfolge, einer Auflösung in der 2. Zz. Der feine Notationsunterschied findet sich in der Verkürzung der beiden Noten der Unterstimmen auf einen 3/16-Notenwert, was die verbleibende 1/16-Note f3 nun zu einer akkordeigenen Tonhöhe macht, zur Quint der Dom. Somit ist wiederum die 2. Zz (Note g3) unbetont, so daß eine Auflösung zur Tonika noch hintangestellt wird.

Um die harmonische Ambivalenz des Akkords zum Ausdruck zu bringen, ist es vorteilhaft, alle 3 Töne des Akkords gleichzeitig anzuspielen und gleichlang auszuhalten, als unaufgelöste Dissonanz.

Mit der 3. Zz wird die Tonika offenbar nun doch erreicht, aber die Spitzennote des4 fungiert als Septim, die Tonika wird zu einer ZD umfunktioniert. Da in der Unterstimme der 3. Zz jedoch nicht der Grundton es3 notiert ist, legt JSB sich noch nicht endgültig fest.

T 7

Die Septim des4 wird nun zu T 7 übergebunden. In der Unterstimme erscheint überraschend die Note e3. Es ist zunächst unklar, welche der beiden Noten dissonant ist. Theoretisch könnte die Note e3 ein Sekundvorhalt sein, der sich nach es3 auflösen würde. Und somit wäre die Note des4 immer noch die Septim des Vortakts, was in einer Auflösung zur Sub, wie in T 2, enden könnte.

Aber die Unterstimme löst sich nicht auf und der weitere Verlauf zeigt, mit der bestätigenden Wiederholung der Terz e4, daß sich die Harmonie des Takts mit den Noten des4 und e3 verwandelt hat zu einem D9-Akkord, nämlich zur ZD der DD. Die Note e3 ist deren Terz. Sie ist zwar zu einer 3/16-Note verkürzt, aber voll auszuhalten, um dieser überraschenden Wendung Nachdruck zu verleihen.

Anmerkung:

Die Überbindung der Note des4 suggeriert eigentlich den Fortbestand der geltenden Harmonie. Trotzdem findet ein Harmoniewechsel statt. Interessant ist nun, daß die Septim des4 der Tonika (in T 6) und die None des4 der ZD der DD (in T 7) die gleiche Frequenz besitzen und deren Verbindung insofern möglich ist. (Das Intervallverhältnis der Grundtöne der ZD der DD (c3) und der Tonika (es4) ist eine kleine Terz, also 6/5. In reiner Stimmung wäre demnach die Frequenz dieser Natursept, von c3 aus berechnet, 6/5 x 7/4 = 21/10 und die der None der ZD der DD (Quint und Tritonus) 3/2 x 7/5 = 21/10, Ohne Verwendung des 7. Partialtons berechnet, weil die Septim nicht zusammen mit dem Grundton erklingt: kleine Septim über kleiner Terz 6/5 x 16/9 = 32/15 und Oktav plus kleine Sekund 2 x 16/15 = 32/15.

Damit wird die harmonische Bedeutung der Haltebögen über den Taktstrich hinweg verständlich. Es wird ersichtlich, wie eng die Maßgaben der reinen Intonation, also den Tonhöhenbeziehungen über ganzzahlige Verhältnisse errechnet, mit denen der harmonischen Prozesse verwandt sind. JSB war sich dessen klar bewußt.

Die Frage, warum die Unterstimme in T 5 zu einer 1/8-Note und in den Tn 6 und 7 nur zu einer 3/16-Note verkürzt wird, erklärt sich daraus, daß in T 5 der Zusammenklang konsonant ist und ein harmonischer Wechsel nur angedeutet wird, aber noch nicht stattfindet, währenddessen die Zusammenklänge in den 1. Zzn der Te 6 und 7 dissonant sind. Letztendlich lassen sie offen, in welche Richtung sie sich auflösen werden. Mit der Verkürzung der Baßnoten um einen 1/16-Notenwert wird zudem eine Akzentuierung der 2. Zz vermieden. Die Betonung in den Tn 5 bis 7 liegt stattdessen eher auf der 3. Zz inklusive der auftaktigen 1/16-Note, weil sich die neue Harmonie erst an dieser Stelle manifestiert.

T 8

Nach einer ostentativen Zäsur, bedingt durch einen abrupten Oktavsprung nach unten, bleibt die Antwort auf diese stark fordernde harmonische Entwicklung weiterhin aus. Eigentlich erwartet man die abschließende DD. Es erklingt jedoch die dissonante Quart f3-b3 und unklar ist erneut, welcher Ton sich „auflösen” wird. Denn theoretisch wäre die Weiterführung der unteren Note, hier also die Note f3 zur Note e3 des Vortakts, denkbar. Dies würde ein Weitererklingen der ZD bedeuten.

Es erfolgt aber die Auflösung von b4 zu a4, was die DD nun realistischer werden läßt. Allerdings findet sich jetzt ein äußerst ungewöhnlicher Bindebogen auf diesen beiden Noten, so daß die Auflösung auf der 2. Zz gerade nicht hervorgehoben wird. Es ist einer der sehr seltenen Fälle in den „Suiten”, wo die Auflösung an einen Vorhalt angebunden ist. Außerdem wird die untere Note f3 nicht in der 2. Zz weitergeführt, was die DD ja festigen würde, und was problemlos spielbar wäre.

Beides, der Bindebogen und der “sparsame” 1/4-Notenwert der Baßnote f3, läßt die angebundene Note a3 noch nicht als Auflösung sondern als Durchgangsnote erscheinen. Die DD macht sich “ganz klein”. Anheim gestellt wird auch, alternativ, ein Trugschluß zur Parallele der DD, also d-moll. Hierfür spricht auch, daß sich die „Sarabande” im weiteren Verlauf den Moll-Tonarten zuwendet.

Jedenfalls wurde derart von JSB ein triumphaler Abschluß nach der dreitaktigen Steigerung und der deklamatorischen Zäsur vereitelt. Die letzte 1/16-Note es3 leitet nur noch „flüchtig” zum nächsten Takt über.

Anmerkung:

Dieser harmonische Vorgang erinnert sehr stark an das “Unterlaufen” der Tp in T 14 des “Prélude” in G-Dur (s. Analyse des “Prélude”, Teil 2).

*

Wie wurde diese Passage nun im Cello-Wettbewerb gespielt?

Interpretation T 5-8 der 11 Teilnehmer

Einige Interpreten verkürzten die Notenwerte in der Unterstimme, einige verlängerten in T 8 die Note f3, um die Auflösung zur DD zu verdeutlichen. Einige eliminierten sogar die Note as3 in der Oberstimme der 1. Zz des T 6, um eine synkopische Überbindung zu simulieren, da der konkave Bogen hier keine Dreistimmigkeit zuläßt. Die dynamische Entfaltung, also die 3-taktige Steigerung und deren “erschrockene” Zurücknahme in T 8, blieb unklar, und derart wurde selten die überdeutliche Zäsur vor T8 realisiert.

*

T 9

Wie beschrieben, manifestiert sich in T 8 der Komposition die „Auflösung” zur DD nicht sehr überzeugend. Die Fluktuation oder Verwischung der Harmonien wird nun von JSB fortgesetzt. In der letzten Passage der 1. Satzhälfte gehen die DD und die Dom, auch die Tonika, eine enge Verbindung ein. Deren Moll-Parallelen treten jedoch in den Folgetakten ebenso ins harmonische Geschehen ein. Der T 9 steht wohl in der Dom, wiewohl ein Hauch der DDp aus dem Takt zuvor erhalten bleibt, wegen der hier erklingenden Baßnote d3. In dieser Deutung wäre die Note b3 in der Oberstimme ein Sextvorhalt, der sich in der 2. Zz zu a3 (1/16-Note) auflöst. Die 1/4-Note d3 im Baß bewirkt, daß die Oktav d4 in der Oberstimme angebunden und die Spitzennote f4 betont ist.

T10

Die Unterstimme es3 in T 10 suggeriert in Verbindung mit der Oberstimme b3 die Tonika. Dadurch, daß sie ebenfalls einen 1/4-Notenwert besitzt, erklingt das obere d4 als Dissonanz (große Septim). Die Spitzennote g4 wird infolge der längeren Bindung über zwei Zzn besonders betont.

Diese Dissonanz es3-d4 verdeutlicht die harmonische Ambivalenz dieses Takts, denn er könnte auch dominantisch gedeutet werden, mit der Note es3 als Quartvorhalt, ein Vorhalt, der diesmal im Baß liegt. Oder, was im Verlauf der „Sarabande” immer mehr in den Bereich des Möglichen rückt, es erscheint hier die Dp. Die Note es3 wäre in dieser Deutung ein Sextvorhalt. (In der 2. Satzhälfte ist die Tp in T 26 naheliegender, weil diese Harmonie bereits in T 15 überdeutlich eingeführt wurde.)

Übrigens wird diese Dissonanz es3-d4 in der 1. Zz als ein klangliches Charakteristikum in den Tn 27ff der 2. Satzhälfte wieder aufgegriffen und fortgesetzt. Jedenfalls sollte sie deutlich zum Klingen kommen, denn danach wirkt die Spitzennote g4 besonders strahlend.

T 11

Der Vorhalt es3 des Vortakts wird in diesem Takt nicht zu d3 aufgelöst sondern weitergeführt zur Note f3. Da die Unterstimme einen 1/4-Notenwert hat, wird die Oberstimme gebunden, wobei jetzt die Note a3 zusammen mit f3 erklingt (im Gegensatz zu T 8). Die Note a3 gehört der Dom und der DD an, aber auch deren Parallele. Die folgende Betonung der Note f3 der 2. Zz läßt insofern die DD oder die DDp vermuten.

Anmerkung:

Es sind ab T 8 mehrdeutige harmonische Interpretationen denkbar, die parallel verlaufen. Vereinfachend ist eine Linie in Dur beschreibbar: DD – Dom – Tonika – (DD) – D (tr?), die andere in Moll: DDp – Dp – DDp – Dp (tr). Diese Dur-Moll-Ambivalenz beherrscht die gesamte 2. Satzhälfte und führt zu den harmonisch überbordenden 5 Schlußtakten.

T 12

Der Triller c3-b2 auf der Abschlußnote der 1. Satzhälfte verunklart das Erreichen der Dom, oder der Dp. Außerdem, wie ist das eigentlich zu verstehen: Handelt es sich dabei um einen Triller auf dem Grundton der Dom? Kann er als Triller auf der Terz b2 der Dp verstanden werden, oder gar als eine Andeutung des Grundtons c3 der Tp? Dieser Triller wirkt „unwirklich”, da ihm keine reguläre Auflösung folgt. Der Abschlußton bzw. die „Endharmonie” fehlt offensichtlich.

Vielleicht läßt sich dieser Triller erst im Nachhinein aufklären, nach der Analyse der 2. Satzhälfte. Denn es wird immer offensichtlicher werden, z. B. in den Tn 28 und 32, daß die Akkorde von zwei latent vorhandenen Harmonien sich oft nur in zwei Tonhöhen unterscheiden.

Dies führt zur Frage, mit welcher Tonhöhe getrillert wird, mit c3 oder a2? Die erste Variante klingt nach “Dur”, die zweite nach “Moll”, was zur Dp weiterführen würde. Näherliegend ist aber die erste Variante, weil sie, analog zum Schlußtakt, sich wieder den Dur-Tonarten zuwendet. In diesem Fall wäre die Note c3 eindeutig der DD zuzuordnen, die Note b2 stünde dann für die Dom. So repräsentiert in T 12 der Triller das “Flimmern” der DD, welche sich immer noch behauptet und “gegenwärtig” ist.

*

Wie wurde diese Passage nun im Cello-Wettbewerb gespielt?

Interpretation T 9-12 der 11 Teilnehmer

Alle punktierten Rhythmen wurden, vereinheitlichend, exakt wie in den vorherigen 4 Tn gespielt, d. h. die Unterstimme wurde auf einen 1/8-Notenwert verkürzt und die Oberstimme nicht gebunden.

Somit erklingen nicht, mit einem ausdrucksstarken Legato in der Oberstimme, die Intervalle d3-d4, es3-d4 und f3-a3. Die Bindebögen in den jeweils 1. Zzn mußte JSB, wie erwähnt, aufgrund der Zweitstimme nicht zusätzlich notieren. In T 11 wurde auch nicht die Betonung der Note f3 der 2. Zz erkannt. Bis auf 2 Ausnahmen wurde der Triller „grundtönig” geendet mit einer mehr oder weniger langen Schlußnote b2, die nicht notiert ist.

*)

Cello-Wettbewerb für Neue Musik und Verleihung des Domnick-Cello-Preises

Staatliche Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst Stuttgart

20. – 25. Januar 2014

Die Teilnehmer:

Charles-Antoine Duflot

Raphael Moraly

Armand Fauchère

Magdalena Bojanowicz

Darima Tcyrempilova

David Eggert

Hugo Rannou

Minji Won

Beatrice Holzer-Graf

Hanna Magdaleine Kölbel

Jee Hye Bae