This is a translation of the post „Die Initialen von J. S. Bach in d-moll“

by Dr. Marshall Tuttle.

This was part of a lecture within the introduction to the project

“IM KLANGSTROM” by Renate Hoffleit and Michael Bach Bachtischa

held in Ulm, Germany on December 7, 2018.

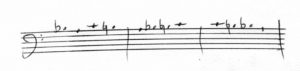

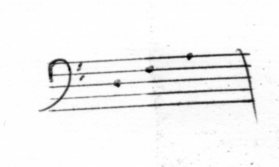

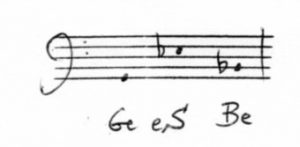

The name BACH consists of 4 note names. First of all, the German note names “h” and “b” are different in German than in English. In English the two notes are represented as “b” and “b-flat” respectively. (In this paper we will adhere to the German spelling. – translator –) In German “b” and “h” are distinct note names:

[plays “b – a – c – h”] (“b-flat – a – c – b” in English, here and in what follows.)

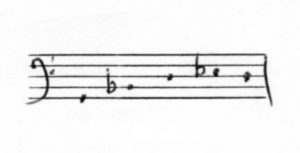

You can also play them in this order:

[plays “a – b – h – c”]

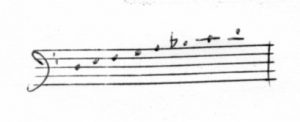

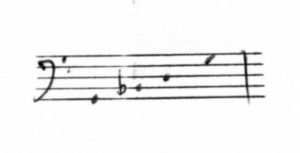

Or like this:

[plays “c – h – b – a”]

They are chromatic pitches each separated by one semitone.

Bach has often utilized these pitch sequences in his composition, as everyone knows, – at least every musician.

Now, in the “Chaconne” in D minor, he adds more of his name to the composition, namely the notes “g” and “es”. (“es” is the German spelling of the note “e-flat”. The translation adheres to the German spelling. – translator –) I don’t think anyone has yet grasped its meaning. Today is the first time that I am making this known. In the overall context these are special pitches.

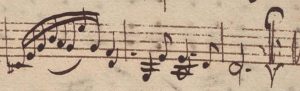

With the “Chaconne” I first noticed that the pitches “b” and “a” are very common:

[plays “b” and “a” in different octaves.]

Most of the time they are the highest pitches or notes in the bass, so:

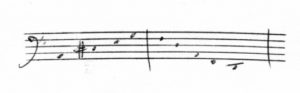

[plays from measure 17]

In measure 18 the notes “b” and “a” are in the upper part:

[plays up to bar 19]

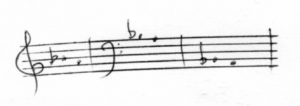

You can hear this chromaticism, that is the notes “c – h – b – a” from BACH in the lower part and the notes “b” and “a” in the upper part.

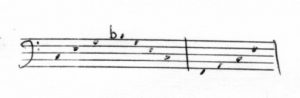

This chromaticism can be found again:

[plays bars 33 to 36]

Again the chromatic sequence “c – h – b – a”.

These pitches are relatively common, because they are related to the key in D minor:

[(V7) – IV – (V7) – VI / i]

The tone “a” is the fifth of D minor:

[plays “d – f – a”]

… is the root of the dominant:

[plays “a – c-sharp – e”]

… and it is also the third of the relative major, F major:

[plays “f – a – c”]

The relative major is always very important for Bach, because it has the same notes as the tonic. Thus, D minor …

[plays the scale in D minor]

… has the same pitches as F major:

[plays the scale in F major]

… they merely begin with different pitches.

This relative major of the key of D minor, – this is a very strange observation – is very often suggested in the “Chaconne”, so he prepares it, even with its own dominant, but again and again he evades it.

Only when it actually appears, it comes massively. But that only happens after a long while, after about 3 minutes, in bar 58 the relative major appears suddenly, there it is fully present, and shortly afterwards it is eliminated and avoided again.

It has therefore a special meaning because it always stands in harmonic focus, but it does not materialize.

Well, we find a “b” as a minor sixth of D minor, as it is very often found in music literature.

[plays “d – f – a – b – a”]

This has a very clear lament character. This effect, this minor sixth, can be found in many melodies, including jazz.

It also occurs, I will talk about that later, in the subdominant (Neapolitan), because it is the note “es”:

[plays “g – b – d – es – d”]

The “b” appears in the minor subdominant as third:

[plays “g – b – d – g”]

… as seventh in the dominant of the relative major:

[plays “c – e – g – b”]

… that resolves into F major:

[plays “f – a – c – f]

… so the “b” is the seventh of the dominant of the relative major.

And also, when the note “c” is not sounded, but in its place the note “c-sharp”, then appears the so-called diminished seventh chord. If you add the bass note:

[plays “a – c-sharp – e – g – b”]

… then it becomes a dominant ninth chord with ninth “b”.

In this manner Bach surprisingly comes to different harmonies by means of the note “b”, because as just shown, for example, simply raising the tone “c” to “c-sharp”, causes the harmonic development to take a completely different turn.

In addition to the note “b”, the note “g” occurs very often. This is the seventh of the dominant:

[plays “a – c-sharp – e – g”]

… which resolves to D minor.

The note “g” appears also in the dominant of the relative major as fifth:

[plays “c – e – g – b” with resolution to F major]

Or, it appears also in the diminished seventh chord as seventh:

[plays “c-sharp – e – g – b” with resolution to D minor]

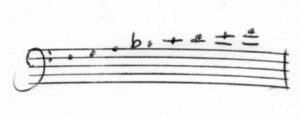

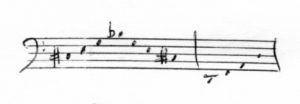

So, and now there is a very special chord that appears at some point in almost all of Bach’s movements, that is the Neapolitan sixth chord. This is the subdominnat with a minor sixth instead of the fifth:

[plays “g – b – es – d – b – g”]

This accord was so named, because it was obviously used very often in the Opera in Naples, because it was felt to be very dramatic, but also very self-pitying. This is because it sounds very dramatic in candences, e. g. in D minor:

[plays “d – f – a – d”]

… then the Neapolitan

[plays “g – b – es”]

… and now to the dominant:

… [plays “e”]

… and this tone sequence:

[plays “es – e”]

… not downwards:

[plays “es – d”]

… but rather upwards

[plays “es – e” and further “c-sharp – a – c-sharp – e – g”]

… creates the dramatic effect. We actually expect it to resolve

[plays “g – b – es – d – b – g”]

… but no:

[plays “g – b – es – e – c-sharp – a” and the resolution to D minor]

Bach uses this Neapolitan very often, mostly in places which are very mysterious, that move very far from the home key.

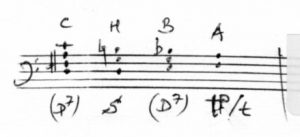

Well, the note names “b – a – c – h” in this piece are clarified, but why does this “es” also occur in very pregnant places? I then considered if it could stand for “Sebastian”.

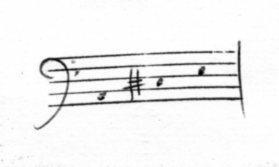

But then what about the “J” from “Johannes”? That does not exist as a note. But, perhaps the first name could be reinterpreted as “Giovanni” – and then we would have a “g”:

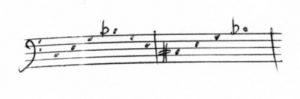

[spielt “g – b – es”]

… which is the bass note of the Neapolitan.

What are the notes of the Neapolitan? It consists of a “g”…

[plays “g – es – b”]

… an “es”, and a “b”. Thus, these are the initials of Bach (JSB).

I actually believe that he associated this chord with his name. A long time later, by accident, I found an article in the German Wikipedia on Bach where he signed his name as “Gio.”.

So, I found my guess confirmed.

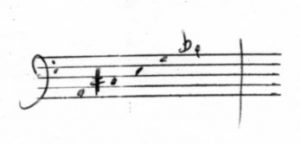

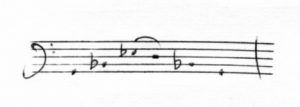

And this “es” has a counterpart, namely the “e”:

[plays “es” and then “e”]

There are places in this work where Bach replaces the “e” with an “es” and vice versa, an “es” with an “e”.

For example, he particularly emphasizes the “e” again at the end:

[plays bar 255]

The top pitch is an “e”.

He could also have written:

[plays bar 255 again and replaces the top note “e” with an “es”]

The “es” has a completely different effect.

So, the “e” is predominant this piece – and I have a guess as to why. But that’s just a guess, when I say it, it doesn’t get out of your head and that’s why I don’t do it. But, I think, that he also associated something with the “e”.

Michael Bach