Michael Bach

Dies ist der erste Teil der Analyse der

Sarabande in D-Dur

Gast:

Burkard Weber

Video:

Interpretation der “Sarabande in D-Dur”

Michael Bach, Violoncello mit BACH.Bogen:

https://youtu.be/YuqXQgfPKkg

Analyse:

https://youtu.be/3vUgrV05eZg

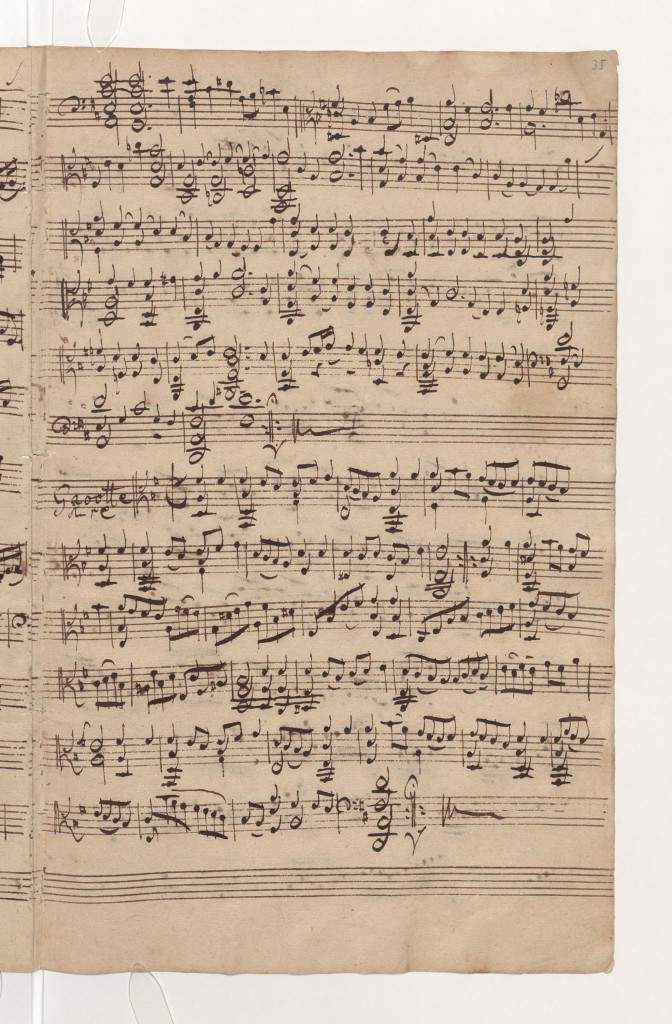

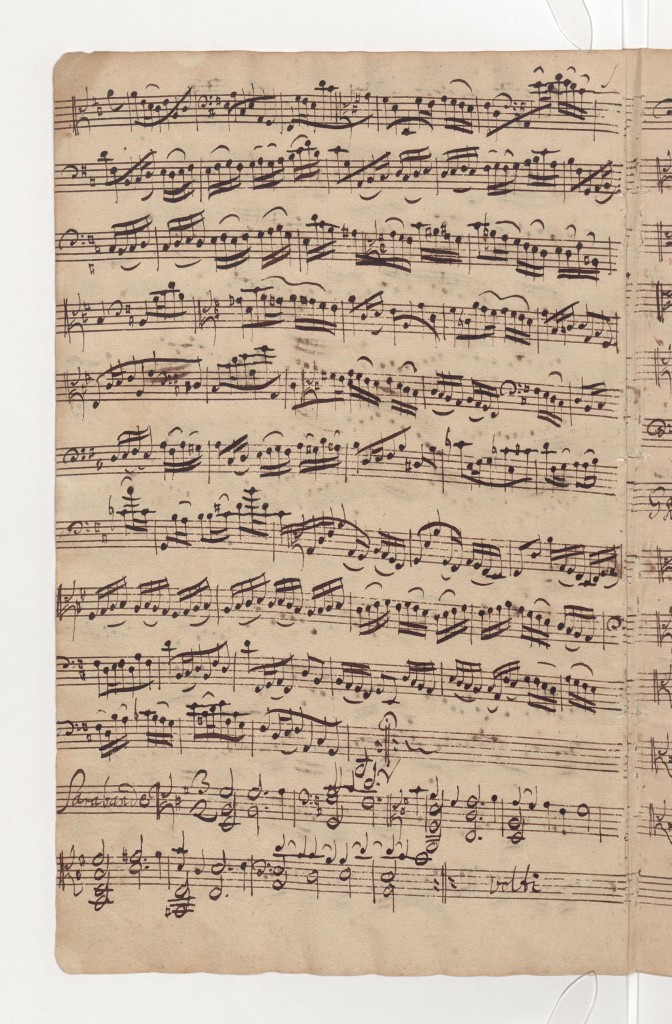

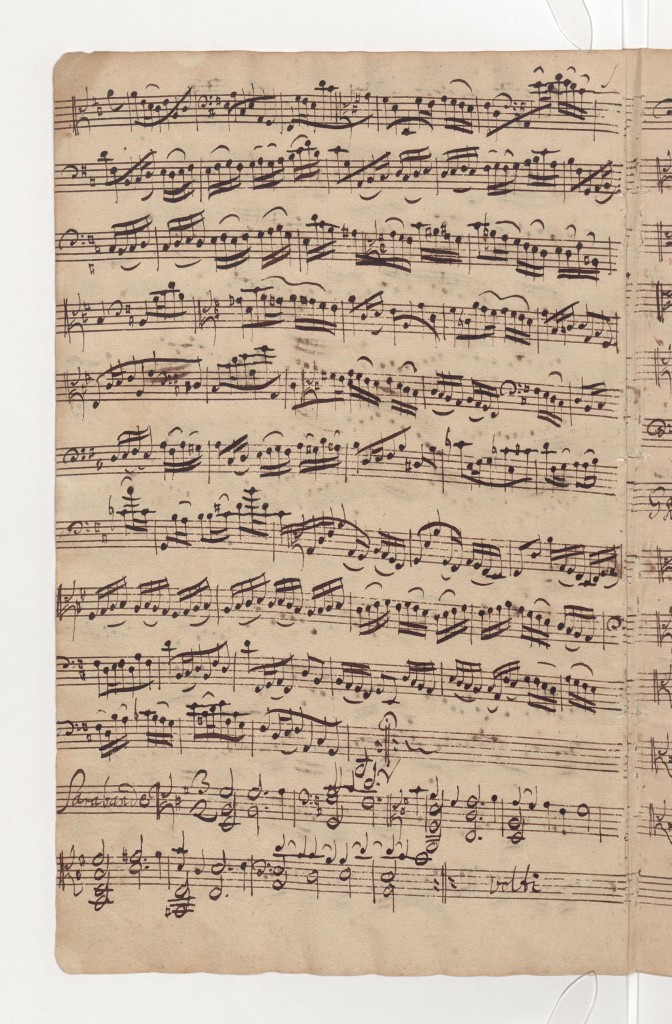

Abschrift von Anna Magdalena Bach, Digitalisat der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – PK

Teil 1

MB (Michael Bach): Hier, in diesem Stück, hat es einen harmonischen Sinn, warum wir einstimmige Passagen haben, warum wir zwei-, drei- und vierstimmige Passagen haben.

Es gibt viele Musiker, oder fast alle, die behaupten, die notierten Notenwerte seien nicht so genau zu nehmen. Meiner Ansicht nach ist es ganz eindeutig so, daß sie genau zu nehmen sind.

Weil, auffällig in diesem Satz ist z. B., daß der Baß meist nicht aufgelöst wird. Das hört man nur dann erst, wenn der Baß auch bis zu Ende gehalten wird.

Takt 1

Nehmen wir den ersten Takt, wir haben also D-Dur. [spielt Takt 1]

Was ist der 2. Klang? Wir haben einen reduzierten D-Dur-Klang.

Wenn darauf ein Schwerpunkt wäre, hätte Bach derart komponiert: [spielt zuerst den zweistimmigen und dann den dreistimmigen Zusammenklang]

Man würde denken, das ist fast das Gleiche.

Wenn man sich aber die ersten 8 Takte anschaut, dann ist die 2. Zählzeit immer reduziert in der Stimmenanzahl. Oft ist ein vierstimmiger Akkord in der 1. Zählzeit und dann ein zweistimmiger, manchmal auch ein dreistimmiger und manchmal sogar ein einstimmiger Klang auf der 2. Zählzeit.

Also, ich kann mir nicht vorstellen, daß das so gespielt wird: [betont den Doppelklang der 2. Zählzeit anstatt den Akkord der 1. Zählzeit]

Es ist eher umgekehrt, daß die 2. Zählzeit eben “unvollkommen” ist und ich spiele sie dynamisch etwas zurückgenommen, weil wir nicht wissen, …

Bei Bach ist das immer so, wenn er von der Mehrstimmigkeit in die Zweistimmigkeit wechselt, dann hat das etwas zu bedeuten. In diesem Fall ist es eine Öffnung zu anderen Harmonien.

Weil, ich könnte mir jetzt diese Harmonie vorstellen: [spielt h-moll]

Nur, der Hörer macht das nicht, weil er muß erst dazu bewegt werden. Z. B. ein cis im Baß (Tonikagegenklang fis-moll) stellt er sich nicht vor. Aber es wäre ja möglich, daß das g nicht am Ende des Takts erscheint, sondern ein gis. Und dann wären wir im Tonikagegenklang oder in der Dominantparallele.

Es erscheint aber das g, und da ist wiederum interessant, daß das einstimmig ist.

Wenn Bach nun dieses vorherige a hätte liegen lassen, dann würde eine kleine Septim entstehen. Das haben wir in dem Stück später, das ist der Takt 13: [spielt Takt 13]

Darüber werden wir noch sprechen. Jedenfalls, wenn ich diese Septim höre, dann denke ich schon an eine Dominante, nämlich das: [spielt a – cis – e – g]

Takt 2

Das passiert aber nicht, sondern es geht weiter mit dem g der Subdominante in der 1. Zählzeit des 2. Takts.

Und hier ist tatsächlich der Schwerpunkt auf der 2. Zählzeit, das ist die Auflösung nach D-dur. Obwohl wir nur 2 Töne haben, ist es klar, das ist D-dur.

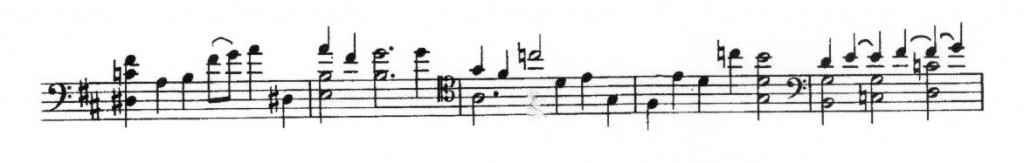

Interessant ist nun der 1. Akkord des 2. Takts: Erstens, er ist nicht spielbar. Die 6. Suite ist ja für ein fünfsaitiges Instrument geschrieben. Wir haben die Schwierigkeit, daß wir die E-Saite nicht haben und deshalb gibt es ein paar Modifikationen.

Aber hier, bei diesem Akkord: [spielt g – g – h – e], das wäre noch spielbar auf einem fünfsaitigen Instrument, aber nicht mehr das: [spielt g – g – h – cis] Das ist nicht mehr spielbar, weil das cis unterhalb der E-Saite liegt.

D. h., man muß hier einen Ton weglassen, wenn man nicht brechen will. Ich habe übrigens noch nie einen Cellisten gehört, der alle 4 Töne spielt.

Welchen Ton lassen wir nun weg? Es gibt 2 Möglichkeiten. Wir haben zunächst diesen Akkord: [spielt g – g – h – e] Da lasse ich auch einen Ton weg, das verdoppelte g, das ist “schmerzlos”.

Weiterhin könnte man so spielen: [spielt g – g – cis], das h weglassen, das oktavierte g, das vorher weggelassen wurde, nun aber spielen. Da haben wir eine gewöhnliche Auflösung vom Tritonus (g – cis) nach D-Dur (fis – d).

Ich mache das nicht, sondern ich möchte die Dissonanz noch verstärken und spiele: [spielt g – h – cis] diese starke Dissonanz mit cis und h.

BW (Burkard Weber): Das ist eine scharfe Auflösung, ist aber schön.

MB: Ja, es steht so da.

Da kommt jetzt noch eines hinzu: die notierten Notenwerte. Es sind in den Unterstimmen Halbe Notenwerte und in der Oberstimme Viertelnoten.

Normalerweise wären jetzt diese Viertelnoten gebunden. Weil immer dann … [spielt eine kurze Passage aus der Gavotte II in D-Dur, Takte 12ff] Hier stehen auch keine Bindebögen, aber in der Unterstimme sind Viertel und in der Oberstimme Achtel.

Das bedeutet in der Regel, also in fast allen Fällen bei Bach, daß die Oberstimme dann gebunden ist. Das bedeutet außerdem, daß die angebundene 2. Note unbetont ist.

Das ist meine Beobachtung, die ich gemacht habe bei der Untersuchung der Bindebögen. Ich spreche da von einem Bindebogen-Kodex. Es gibt ungefähr 10 Regeln mit kleinen Modifikationen.

Eine Regel ist die, daß wenn in einem Akkord, unten oder oben, längere Notenwerte stehen und eine Stimme sich bewegt, dann ist diese gebunden.

Und dann kommt noch eines hinzu, was ich erst beim Studium der Chaconne für Violine solo entdeckt habe. Das hängt damit zusammen, daß wir am Cello nicht so stark akkordische Sätze haben, wo so etwas vorkommt. Daß wenn längere und kürzere Notenwerte zusammen gespielt werden, dynamisch so gespielt wird, als ob ein alles umfassender Bindebogen da wäre.

Ich nehme mal das: [spielt Takt 4] Daß nämlich nach dem Bindebogen die erste Note betont ist.

Das ist alles ein wenig schnell und kompliziert und vielleicht nicht so leicht nachvollziehbar …

Hier, in der Sarabande in D-Dur, gibt es nun diese Ausnahme, daß Bach manchmal einen Bindebogen notiert (Takte 4 und 7) und manchmal nicht in solchen Fällen (Takte 2, 3 und 6).

Das bedeutet, z. B. wenn er in Takt 4 einen Bindebogen schreibt [spielt 1. Zählzeit in Takt 4], ist die Auflösung (fis) unbetont und der nächste Ton (g) betont. Hätte er diesen Bindebogen nicht geschrieben, dann wäre die Auflösung nicht unbetont, sagen wir mal so. Das kommt an anderer Stelle auch vor (Takt 23).

Und das bedeutet, daß immer dann, wenn kein Bindebogen steht, der 2. Zusammenklang nicht abgeschwächt ist, sondern eher sogar noch verstärkt wird [spielt 1. Zählzeit von Takt 2].

Interessant ist ja hier, auch wieder, daß der Baß nicht aufgelöst wird. Er könnte ja vom g zum fis gehen. Das fis findet sich in der Stimme oben, aber nicht im Baß [spielt 2. Zählzeit von Takt 2].

Die Tatsache, daß Bach nicht auflöst, steigert die Erwartungshaltung.

Im folgenden Takt erklingt zwar D-Dur [spielt 1. Zählzeit von Takt 3], aber eine direkte Auflösung ist das nicht.

Wir werden jetzt sehen, wie sich das weiter entwickeln wird. Der 1. Takt hat uns bereits den Hinweis gegeben, ein Fragezeichen: Warum läßt Bach hier, in der 2. Zählzeit, den Baß weg?

Hier hingegen [spielt Takt 2 und 3] ist die 2. Zählzeit betont, das ist das Paradoxe in diesem Stück, daß oft die 2. Zählzeit betont ist, obwohl sie in der Stimmenanzahl reduziert ist.

Continue reading →