![]()

Michael Bach Bachtischa

RYOANJI and ONE13

The five individual compositions of the 1980s RYOANJI series for voice, oboe, flute, trombone and double bass by John Cage have eight different intervals as pitch spaces, within which glissando lines are performed.

In ONE 13 for cello and curved bow only eight pitches follow each other: f#’, g”, g”, f”, d’, d”, a’, eb”. The piece consists therefore of eight parts, each of them is devoted to one single pitch and its reiterations.

RYOANJI and ONE 13 have the same formal structure: eight sections and four parts. In a performance, one part is played live, while the three other parts, recorded by the same soloist beforehand, are played back over loudspeakers which are distributed in space.

The fundamental difference between RYOANJI and ONE 13 thus lies in the fact that single pitches instead of glissando lines (within the interval delimitations) are notated.

The metamorphosis from RYOANJI to ONE 13 occurred during a collaboration between John Cage and myself in July 1992 in New York City. In determining a total of eight intervals for a planned version of RYOANJI for cello a chance operation produced the result, that the third interval should be a unison prime, the interval f#’ – f#’. John Cage had not anticipated a unison prime, virtually a zero-interval, as the result of the chance operation and wanted to pass it over as useless and simply ignore it.

That unpredictable prime created through chance immediately cast its spell over me. In the two following days I had the opportunity then to convince John Cage of this chance result by demonstrating to him twenty different and multiphonic f#’ sounds on the cello (Examples 2 and 3). This multitude of sounds is made possible with the curved bow, with which all strings of the cello can sound simultaneously, and through the extensive use of harmonics, for which I had already developed a number of novel performance techniques.

When listening to these twenty different f#’ sounds, it becomes clear that there are both subtle differentiations in the timbre and in the pitches, for the use of partials implicates by definition a microtonal understanding of pitches, whereby equal temperament is given up. Each individual pitch of the unison sound – this is most clearly evident in the case of partials – is derived from its own initial pitch, the fundamental. For instance the f#’ can be the second partial of f#, the third partial of b, the fourth partial of f# and the fifth partial of d. Unexpectedly from a unison an ambiguous multiphonic sound develops, which increasingly gains in complexity, the more complicated the derivation of its individual pitches is.

This unusual interpretation of the unison prime phenomenon, which challenges the identity of the pitches, of which it consists, and corresponds in a sense to a traditional question of the Ryoan-ji stone garden in Kyoto: Why is it that “one” of a total of fifteen rocks always remains invisible to the human eye, no matter from which position on the visitor’s stand the rock garden is viewed? The question of the Ryoan-ji about the invisible, but existing rock leads to the statement, that sensory impression and reality are not congruent, that the apperception of reality succeeds only partially and in an incomplete way. The question leads so to speak, first to an obvious answer, to the fourth dimension, time, because the viewer will have to change his location to ever see all the rocks. So “movement” would be an answer, which is paradoxically and at first glance not suggested by the rigid mineral composition of the rock field.

ONE 13 shows a similar case. In the unison prime one pitch overlies and covers up the other. The superficial fact, that only one single pitch sounds, suggests a static listening experience. This litany-like insisting on a supposedly unchanging pitch is at the same time the gate to new discoveries, because it requires virtually a mental liberation from this pitch to become aware of those movements, which occur inside these unison prime sounds.

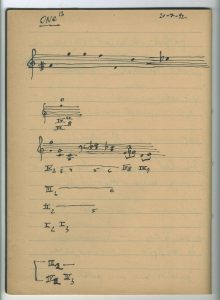

The crucial link between RYOANJI and ONE 13 is my drawing 18-7-92 (Sketches for Ryoanji), which has the date [7/18/92] of its genesis as its title (Ex.1), because it captures and illustrates exactly, in statu nascendi, the transforming moment of the thematic orientation toward the unison prime. Further the unison prime f#’ in 18-7-92 is the key issue, where the visual perception of the work becomes an acoustic one. The visual superimposition of the two f#’ note heads (two f#’ notes should really be juxtaposed) is also an acoustic overlapping, for which the word “interpenetration” is more indicative. Sound waves of the simultaneously sounding pitches do not cover each other up, but instead interfere with each other, – and in this respect the one f#’ always remains present beside the other one. This insight, which is based on an exploring kind of listening led directly to the working out of the unison prime variants on the cello, the twenty different f#’ sounds.

In ONE 13 this reformed understanding of the unison prime f#’ is equally transferred to other pitches. On 20 July 1992, John Cage told me that he wanted to transfer the unison prime idea, which now also fascinated him, to further pitches, with the words: ” … and this will be ONE 13.”

The contexts, which have been partly shown here offer sufficient enough motives for me to agree with the suggestion of The John Cage Trust and C. F. Peters Corporation New York to publish ONE 13 now under both of our names. Thanks especially to Merce Cunningham, who sent me copies of John Cage’s manuscript pages of ONE 13 in October 1992, and to Don Gillespie, who since John Cage’s death never lost sight of the plan to publish ONE 13 in this form.

Translation: Sabine Feisst

*) The octave designation corresponds to the one used in The New Harvard Dictionary of Music and in the older Helmholtz system, where c’ is the middle C.

**) Michael Bach, Fingerboards & Overtones, Munich 1991.

![]()

Michael Bach Bachtischa

RYOANJI und ONE13

Die fünf Einzelkompositionen der Werkreihe RYOANJI für Stimme, Oboe, Flöte, Posaune und Kontrabaß von John Cage aus den 80er Jahren haben acht unterschiedliche Intervalle als Tonräume, innerhalb derer Glissandolinien ausgeführt werden.

In ONE 13 für Cello und Rundbogen folgen lediglich acht Tonhöhen aufeinander: fis1, g2, g2, f2, d1, d2, a1, es2. Das Stück besteht folglich aus acht Teilen, wovon jeder einer einzigen Tonhöhe und dessen Wiederholungen gewidmet ist.

RYOANJI und ONE 13 haben den gleichen formalen Aufbau: acht Teile und vier Stimmen. Bei einer Aufführung wird eine Stimme live gespielt, währenddessen die anderen drei Stimmen, vom selben Solisten voraufgenommen, über Lautsprecher, im Raum verteilt, wiedergegeben werden.

Der grundsätzliche Unterschied zwischen RYOANJI und ONE 13 besteht demnach darin, daß anstelle von Glissandolinien (innerhalb der Intervall-Abgrenzungen) einzelne Tonhöhen notiert sind.

Die Metamorphose von RYOANJI zu ONE 13 vollzog sich während einer Zusammenarbeit von John Cage und mir im Juli 1992 in New York. Bei der Ermittlung der insgesamt acht Intervalle für eine geplante Version von RYOANJI für Cello ergab die Zufallsoperation, daß das dritte Intervall eine Prim, das Intervall fis1 – fis1 sein sollte. John Cage hatte eine Prim, also quasi ein Null-Intervall, als Zufallsergebnis nicht antizipiert und wollte es als unbrauchbar, einfach unbeachtet, übergehen.

Jene unvorhergesehene, durch den Zufall erschaffene Prim, zog mich sofort in ihren Bann. In den beiden Folgetagen hatte ich nunmehr Gelegenheit, John Cage von diesem Ergebnis des Zufalls zu überzeugen, indem ich ihm 20 verschiedene und mehrstimmige fis1-Klänge am Cello vorführte (Abb.2 und 3). Diese Vielzahl wird ermöglicht mit dem Rundbogen, der alle Saiten des Cellos zugleich erklingen lassen kann, sowie durch die extensive Verwendung von Obertönen, für die ich eine Reihe von neuartigen Spieltechniken bereits entwickelt hatte.*)

Beim Hören dieser 20 unterschiedlichen fis1-Klänge wird deutlich, daß sowohl feine Differenzierungen in den Klangfarben, als auch in den Tonhöhen bestehen. Denn die Verwendung von Partialtönen impliziert per definitionem ein mikrotonales Verständnis von Tonhöhen, wobei die temperierte Stimmung aufgegeben wird. Jeder einzelne Ton des Unisono-Klangs – am deutlichsten zeigt sich das bei Partialtönen – leitet sich von einem ihm eigenen Ausgangston, dem Grundton ab. So kann z.B. das fis1 der 2. Partialton von fis, der 3. Partialton von H, der 4. Partialton von Fis und der 5. Partialton von D sein. Unversehens hat sich aus einem Einklang ein vieldeutiger Mehrklang gebildet, der zunehmend an Komplexität gewinnt, je komplizierter die Herleitung seiner Einzeltöne sich gestaltet.

Diese ungewöhnliche Deutung des Phänomenon Prim, die die Identität der Töne, aus denen sie sich konstituiert, hinterfragt, entpricht in gewisser Weise einer traditionellen Fragestellung des Ryoan-ji Steingartens in Kyoto: Warum bleibt immer „ein” Stein von insgesamt 15 Steinfelsen, egal von welchem Standpunkt auf der Besuchertribüne aus der Steingarten betrachtet wird, dem menschlichen Auge verborgen? Die Frage des Ryoan-ji nach dem nicht sichtbaren, aber vorhandenen Stein mutiert zu einer Aussage, daß Sinneseindruck und Wirklichkeit nicht kongruent sind, daß die Apperzeption der Realität nur ausschnittsweise und unvollkommen gelingt. Die Frage führt gewissermaßen, in einer ersten näherliegenden Antwort, zur vierten Dimension, der Zeit, weil der Betrachter seinen Standort wechseln muß, um aller Steine jemals ansichtig zu werden. Eine Antwort wäre also „Bewegung”, die, paradoxerweise, durch die starre mineralische Komposition des Steinfelds vordergründig nicht nahegelegt wird.

Ähnlich verhält es sich bei ONE 13. In der Prim überlagert und verdeckt ein Ton den anderen. Die vordergründige Tatsache, daß nur eine einzige Tonhöhe erklingt, suggeriert ein statisches Hörerlebnis. Dieses litaneihafte Insistieren auf einer vermeintlich unveränderten Tonhöhe ist zugleich die Pforte zu neuen Entdeckungen, denn es erfordert geradezu eine mentale Befreiung von dieser Tonhöhe, um derjenigen Bewegung gewahr zu werden, die sich im Innern dieser Prim-Klänge ereignet.

Das entscheidende Bindeglied zwischen RYOANJI und ONE 13 ist meine Zeichnung 18-7-92 (Aufzeichnungen zu Ryoanji), die das Datum ihres Entstehens als Werktitel trägt (Abb.1), weil sie exakt, in statu nascendi, den transformierenden Augenblick der thematischen Ausrichtung auf die Prim festhält und veranschaulicht. Des weiteren ist die Prim fis1 in 18-7-92 der Angelpunkt, wo die visuelle Perzeption des Werks in eine akustische umschlägt. Die visuelle Überdeckung der beiden fis1-Notenköpfe (eigentlich müßten zwei fis1-Noten nebeneinander stehen) ist gleichermaßen ein akustisches Überlappen, wofür jedoch die Bezeichnung „gegenseitige Durchdringung” charakteristischer ist. Schallwellen gleichzeitig erklingender Töne verdecken sich nicht, sie interferieren, – und insofern bleibt neben dem einen fis1 das andere immer präsent. Diese Einsicht, die auf einem forschenden Hinein-hören beruht, führte unmittelbar zur Ausarbeitung der Prim-Varianten am Cello, die 20 verschiedenen fis1-Klänge.

In ONE 13 wird dieses reformierte Verständnis der Prim fis1 auf andere Tonhöhen gleichermaßen übertragen. Am 20. Juli 1992 teilte mir John Cage mit, daß er die, ihn jetzt ebenso faszinierende, Prim-Thematik auf weitere Tonhöhen ausdehnen wolle, mit den Worten: „ … and this will be ONE 13” **).

Die hier stellenweise aufgezeigten Zusammenhänge sind für mich Beweggründe genug, dem Vorschlag des The John Cage Trust und der C.F. Peters Corporation New York zuzustimmen, und ONE 13 , nun unter unserer beider Namen, zu veröffentlichen. Ich danke insbesondere Merce Cunningham, der mir Kopien von John Cages Manuskriptseiten zu ONE 13 im Oktober 1992 zusandte und Don Gillespie, der seit John Cages Tod das Vorhaben, ONE 13 in dieser Form zu veröffentlichen, nie aus dem Blick verlor.

*) Michael Bach, Fingerboards & Overtones, München 1991.

**) „… und das wird ONE 13 sein.”

John Cage, f sharp, Fax an Michael Bach 03. August 1992

![]()

Michael Bach Bachtischa

RYOANJI et ONE13

Au cours des années 80, John Cage composa les cinq pièces individuelles qui constituent le cycle RYOANJI pour voix, hautbois, flûte, trombone et contrebasse. Ces pièces sont caractérisées par l’emploi de huit intervalles différents qui constituent autant d’espaces sonores à l’intérieur desquels sont exécutés des traits de glissando.

Dans ONE 13 pour violoncelle avec archet courbe, les notes suivantes apparaissent successivement: fa#3, sol4, sol4, fa4, ré3, ré4, la3, mi bémol4. La pièce est ainsi divisée en huit sections, chacune consacrée à une seule note et à ses avatars.

RYOANJI et ONE 13 possèdent la même structure formelle, à savoir huit sections et quatre voix. Lors d’une exécution publique, l’une des quatre voix est interprétée “live” alors que les trois autres, pré-enregistrées par le soliste, sont restituées grâce à des haut-parleurs distribués dans l’espace.

Dans RYOANJI la notation consiste en des lignes de glissando inscrites à l’intérieur des limites intervallaires, tandis que dans ONE 13 ce sont des sons individuels qui sont notés.

La métamorphose de RYOANJI en ONE 13 s’accomplit durant ma collaboration avec John Cage en juillet 1992, à New York. Alors que nous procédions à l’opération de détermination aléatoire des huit intervalles en vue d’une version de RYOANJI pour violoncelle, le hasard détermina que le troisième intervalle devait être l’unisson fa#3-fa#3 *). Or, l’unisson – un intervalle qui peut être considéré comme “nul”- n’entrait pas dans les prévisions de John Cage. Il voulut donc faire l’impasse sur ce résultat et simplement ne pas tenir compte de l’unisson qu’il considérait comme inutilisable.

Pour ma part, je tombai immédiatement sous le charme de cet unisson inattendu, généré par le hasard. Durant les jours qui suivirent, je pus convaincre John Cage en lui démontrant sur mon violoncelle vingt fa#3 différents que je pouvais exécuter à plusieurs voix (figg. 2 et 3). Cette multiplicité était rendue possible grâce à l’archet courbe, avec lequel il est possible de faire résonner jusqu’à quatre cordes simultanément, et aussi grâce à l’emploi systématique des sons harmoniques, pour lesquels j’avais déjà élaboré toute une série de nouvelles techniques exécutives **).

À l’écoute de ces vingt différents fa#3, de subtiles nuances de timbre et de hauteur apparaissent. Ainsi, l’utilisation des sons harmoniques implique, par définition, une intelligence microtonale des hauteurs de son et l’abandon du tempérament égal. Chacun des sons constituant l’unisson – et cela est particulièrement clair dans le cas de sons harmoniques – est issu de son propre diapason de départ. Par exemple, le fa#3 peut correspondre à l’harmonique 2 de fa#2; il peut être aussi l’harmonique 3 de si1, l’harmonique 4 de fa#1, ou encore l’harmonique 5 de ré1. De façon inattendue, il se développe à partir de l’unisson un son multiple et complexe qui augmente en complexité à mesure que la dérivation de ces éléments devient plus lointaine.

Cette interprétation inhabituelle du phénomène de l’unisson – qui remet en question l’identité même des éléments constitutifs de cet intervalle “zéro” – correspond d’une certaine façon à l’interrogation traditionelle du jardin de pierre Ryoan-ji de Kyoto: pourquoi “une” des quinze pierres demeure-t-elle invisible à l’oeil humain, quel que soit la place occupée par l’observateur sur la tribune? L’énigme de la pierre du Ryoan-ji, invisible mais présente, est porteuse du message que perception sensorielle et réalité ne coïncident pas, que l’appréhension de la réalité ne réussit que de façon partielle et imparfaite. Une première réponse à la question du Ryoan-ji est évidemment la “quatrième dimension”, le temps. En effet, pour pouvoir voir toutes les pierres, l’observateur doit nécessairement avoir occupé plusieurs postes d’observation. La réponse pourrait donc être aussi le “mouvement”, ce qui, paradoxalement, n’est guère suggéré par la rigide composition minérale du champ de pierre.

Quelque chose de similaire se produit dans ONE 13. Dans l’unisson, les notes se superposent et se dissimulent l’une l’autre. Le fait qu’en apparence une seule note résonne suggère une expérience d’écoute statique. L’insistance quasi obsessionnelle sur une note présumée invariable ouvre la porte sur de nouvelles découvertes. Il s’agit en fait de se libérer mentalement de cette note afin de devenir conscients des mouvements qui se produisent à l’intérieur de l’unisson.

Mon dessin 18-7-92 (Esquisses pour Ryoanji) constitue le lien décisif entre RYOANJI et ONE 13. Cette esquisse, dont le titre correspond à sa date de création (fig.1), représente exactement, in statu nascendi, le moment de changement de l’orientation thématique vers l’unisson. L’unisson fa#3 est en fait le point essentiel de 18-7-92 , là où la perception visuelle de l’oeuvre se change en perception acoustique. La superposition visuelle des deux fa#3 (les deux notes devraient en principe figurer l’une à côté de l’autre) correspond aussi à un chevauchement acoustique et, de ce fait, le terme d’interpénétration serait plus descriptif. En réalité, les ondes sonores des notes jouées simultanément ne se masquent pas l’une l’autre, elles interfèrent l’une avec l’autre et, ce faisant, un fa#3 reste toujours à côté de l’autre. Cette compréhension, qui repose sur une écoute intériorisée et exploratrice du phénomène, mena directement à l’élaboration des variantes d’unisson pour le violoncelle, à savoir les vingt différents fa#3.

Dans ONE 13 cette compréhension nouvelle de l’unisson fa#3 est appliqué également à d’autre notes. Le 20 juillet 1992, John Cage me dit que la thématique de l’unisson commençait à le fasciner et qu’il désirait l’étendre à d’autres notes, en précisant: “…and this will be ONE 13” ***).

Les circonstances que j’ai évoquées en partie ici me paraissent constituer des motifs suffisants d’accepter la proposition de The John Cage Trust et de la C.F. Peters Corporation New York de publier ONE 13 sous nos deux noms réunis. Je remercie tout particulièrement Merce Cunningham de m’avoir envoyé des copies des pages manuscrites de John Cage concernant ONE 13. Merci aussi à Don Gillespie qui, depuis la disparition de John Cage, n’a jamais perdu de vue le projet de publier ONE 13 sous la présente forme.

Traduction: Dr. Philippe Borer

*) Dans le système de repérage des hauteurs en usage en France, le do de la corde grave du violoncelle reçoit l’indice 1 (do1). Le fa#3 se trouve donc une tierce mineure au-dessous du LA de référence, fixé à 440 Hz (la3). Par contre,dans le système adopté dans les pays germaniques (notation Helmholtz) le fa#3 s’écrit “fis1”.

**) Michael Bach, Fingerboards & Overtones, Münich 1991.

***) “…et cela deviendra ONE 13”

Michael Bach Bachtischa, ONE13 (Skizzenheft, New York City 1992)