This is a translation of the post

Urtext = Klartext? – eine Analyse der Sarabande in D-Dur, Teil 4 (Takt 25-32)

by Dr. Marshall Tuttle

Michael Bach

This is the fourth part of the analysis of the

“Sarabande” in D Major

Guest:

Burkard Weber

Video:

Interpretation of “Sarabande in D Major”

Michael Bach, Violoncello with BACH.Bogen:

https://youtu.be/YuqXQgfPKkg

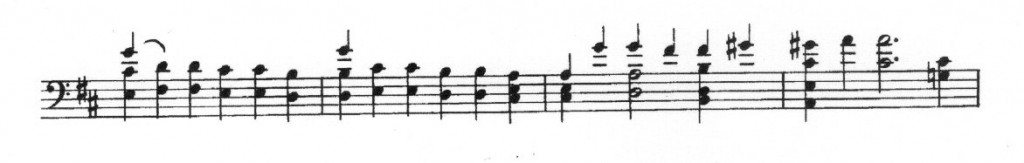

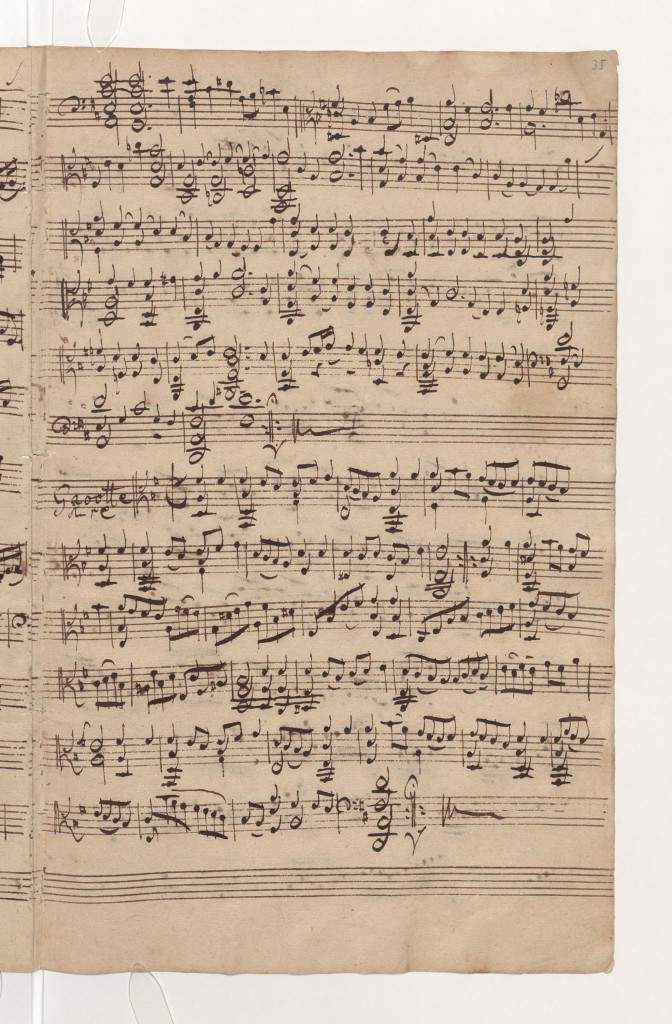

Copy of Anna Magdalena Bach, digital copy from the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin – PK

Part 4

In the following 3 bars, four-voice chords are on the first beat. The first is also emphasized, the second also … only by being four-voice. This must also be taken into account, as I shall say, by the fact that the rules of the Slur Code [intersect]…

There are times when the slurs suggest that a beat is unstressed, but there is suddenly a four-voice chord. This is, of course, accentuated.

In bar 25, Bach wrote a tie in connection with a slur. That is, the intermediate beat between the 2nd and 3rd beats is emphasized. This is the tonic.

So, we were “thrown out of rhythm”, so to speak.

Measure 26

On the first beat Bach notates a slur. The tritone of the second beat is emphasized, the E is tied the repetition of the E can not be tied, nevertheless, as a result of the dotted half note in the upper voice, a decrescendo arises:

Measure 27

To D minor, which is a surprise. D major is actually expected, but D minor appears.

Measure 28

The dominant is sounding. The note A# in the bass indicates the dominant of B minor.

Harmony in B minor, which had not yet been prepared, is now established by means of a four-voice chord with the memorable A# in the bass, that is, with its own dominant.

This is the relative minor: B minor (first beat).

Bach writes here for the first time rests in the lower voice. This is very unusual.

I also asked myself what harmonies do we have here? Could that be the dominant, for example? [plays the second beat with C# and A in the lower voices] Could be possible.

Or do we slowly return from B minor to G major, to the subdominant? It could even develop the tonic.

I once looked up – when it comes to pitches, I sometimes look at Kellner, this is the 2nd transcript we have. Actually, the first one, created before that of Anna Magdalena Bach.

There I actually found something i was looking for, because Kellner writes a small grace note before the E, namely a C#. Thus, the dominant is clear. But, I believe that is an ingredient of Kellner’s. Sometimes you find something like this, he was a composition student of Bach’s.

But Kellner has obviously also “scratched his head”: What are actually here for harmonies, where these rests are? Bach could have written a few more notes, so we could know where we are in harmony. Bach purposefully did not do that.

And then a special feature at this point: There is a small slur and is actually a tie above the high G.

This is so uncommon to link a sixteenth note syncopated before the next beat, so that I have been wondering for a long time whether this slur has just gotten out of place. Would not this slur really be on the F#? But the F# is the third of the tonic and would thus be more highlighted with a small slur …

In any case, no matter where the slur stands, the top note G would be accentuated in both cases.

So if I play [plays the slur on the note F#], the second beat would be accentuated with the top note G, according to the Slur Code.

If, on the other hand, I play [playing a tie on the note G], the top note G is also accentuated. I even prolong the G a little.

This version seems to me to be more exceptional. That is why I play this slur as it stands. There is no reason, from my point of view, to play it differently.

And now, on the third beat is a clear dominant seventh chord, more precisely, the secondary dominant to the subdominant. There is another pause in the bass in the bar.

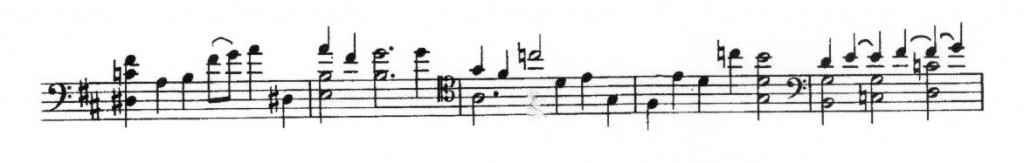

Measure 30

The resolution to the subdominant with sixth takes place, it is the same chord as in bar 2, exactly the same pitch constellation. Here, however, with a slur, thereby emphasizing the tonic of the second beat.

In the second beat is not a slur, but again in the third beat, whereby the dissonance in the following bar is emphasized.

The harmony of the first beat is unclear, we do not yet know what the result of this will be: [plays the first beat with a slur]

The second beat is unstressed. There could be a resolution in the upper voice [plays D – C#], but it does not happen. The note G is not tied. although half notes are in the bass and in the upper part. But we have already discussed the exception in this movement.

In the third beat we have only two-part voicing.

Here is the four-part chord. I already mentioned that because you spoke of the sonority at the beginning, …

BW: Yes, of course.

MB: … in connection with the end of the first part, because you add more notes. Here we see that Bach omits pitches on the third beat of the preceding bar. He could have left the note A in the bass.

The reason is the following, Bach would like the volume of the four-voice chord in the end to distinguish it from the preceding sound.

And, there is one more thing, it is here the first time, where the tonal space extends under the G-string. This deep D had not previously occurred. Everything played has been over the G string.

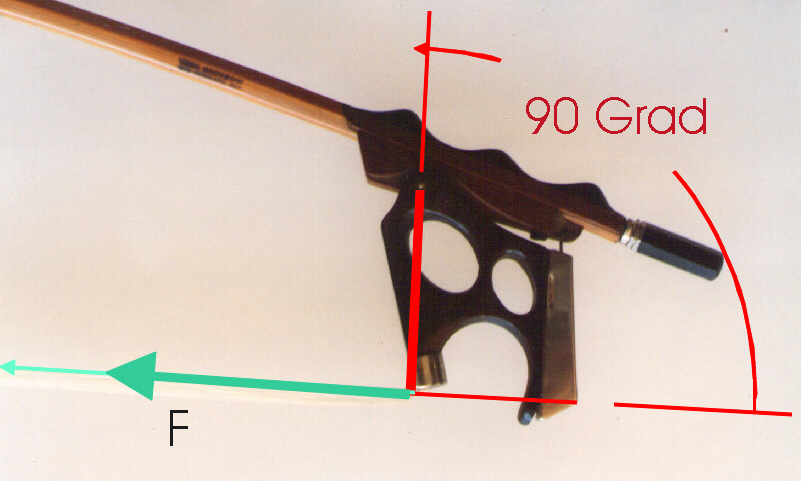

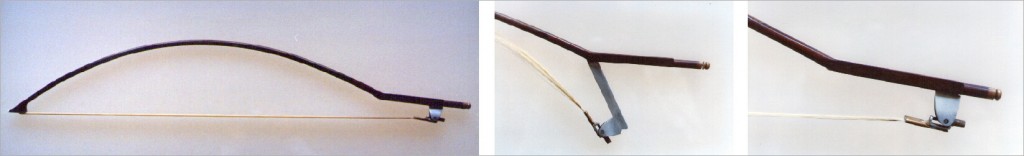

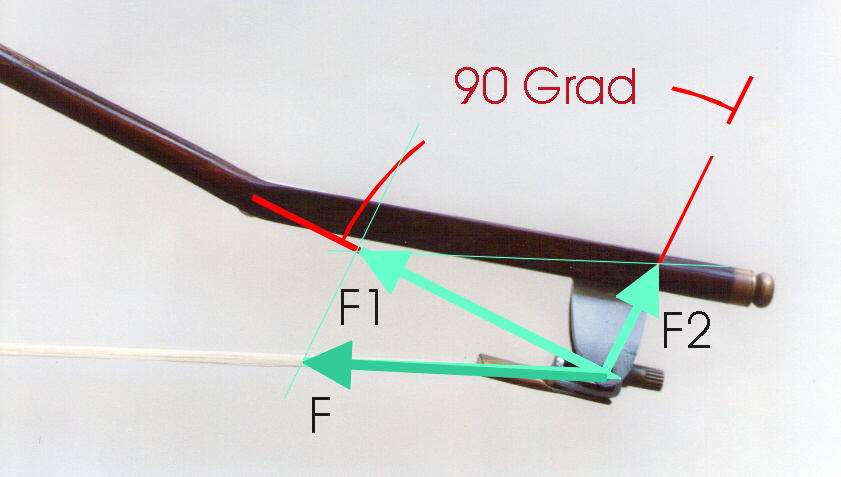

And, at the same time, there arises an interference between the lowest and highest strings, namely, between D and C#, a major seventh. This I can just play with the gently curved bow. you can of course execute it more smoothly with the highly arched bow.

The bass note D I try to keep as long as possible. The conclusion is then two-part, somewhat more sonorous than the end of the first part.

BW: This has a certain greatness that Bach is still producing this friction with the C# in this chord in another situation. This makes the door open a little once again. This extension is not expected, but rather a final conclusion. And then that friction comes in. That’s just Bach.

MB: Yes, and it is also thematic. I had already spoken about the cambiata [plays G – E – F#], and from this develops [plays G – F# – G – E – F# from bar 4], and [the upper voice of bar 7f] And from this develops [plays the bars 16ff and the bar 21], now even two-part.

And these repetitions are actually the result of the augmentation of this small cambiata: [plays G – E – F# (measure 4), then E – C# – D (measure 2)]

This is exactly what we have in the end: [plays mid-voice of bar 31 and the upper-voice of bar 32]

BW: Yes, beautiful. It’s totally interesting. Very good, really.

MB: Yes, you can do it all only with the curved bow.

BW: The curved bow is absolutely necessary for this piece. I mean, only the curved bow makes it possible to explore the meaning of this work. Arpeggiating with the straight bow change… the breaking of the chords shifts the existing rhythm. The listener, as a result of the decomposition of the chords with the straight bow, must reconstruct them mentally again.

MB: This is one thing. If we have a consonant chord, like G major or D major, one could theoretically not need to keep all the notes to the end.

We can also play them like this: [plays a three-part D major sound and continues this two-part, then ending with the upper voice alone.]

BW: Yes, of course, but important is how it starts: [sings pa-da-]

MB: I wanted to say something else. It is not just that all notes of a chord sound together at the beginning and then the upper voice is sustained for melodic reasons, and the lower notes are left. This is possible when we have resolutions such as at the end: [plays measure 32 with an arpeggio]

Here I could imagine something like that too. But in this movement it is as we have seen [the beginning of bar 2] that the bass note should be sustained because it is not resolved here.

In this movement, only one bass note is immediately resolved, namely, at the end (bar 28f) to B minor: [plays A# – B]

Thus: [plays measure 28 with resolution to the bass note B.] Such effects can only be obtained if the other bass notes, which are not resolved, can also be sustained. This can only be done with the curved bow.

You can not break chords up and then down again: [plays a D major chord with an arpeggio up and then down] If you want to end a chord including the bass note, you can only use a bow that allows you to have multiple voices.

I’m just wondering if … I do not know a single movement from the suites where I do not play, if possible, the notated note values.

Because, there is always a compositional reason for the note values. It is so, I play the note values not merely because they are writtten so, but because they make sense.

In this movement this was shown. But there are still quite different cases, where Bach even notates a prime in the bass in the Chaconne for violin (bar 13). Even if you can do it on the violin, it does not go on the cello. The prime will hardly play because you do not hear it.

This prime has a reason: that the lower voice is accentuated, that further development takes place in the lower voice. This can be done wonderfully with the curved bow by simply playing the full chord and releasing the upper notes to sustain the bass note: [plays D major and ends with the bass note]

You do not have to play like this: [plays arpeggio up and then down]

BW: That makes no sense.

MB: Traditionally, this is done like that with the straight bow.